Jonathan Evison’s third novel, The Revised Fundamentals of Caregiving, is a highway ballad, a book that, like so many before it, adheres to the notion that America’s open roads are portals to catharsis and redemption. It’s a story of heartbreak and healing, and it opens with a portrait of a defeated man.

Befitting his monotonous moniker, Benjamin Benjamin is a Pacific Northwesterner for whom every day is equally uninspiring. Ben’s haunted by what he refers to as “the disaster,” and though the details of this tragic event aren’t revealed to the reader until much later in the proceedings, we know that it has caused a rupture in the happy home life he once shared with his wife and two children. A former stay-at-home dad, he’s become a recluse with money troubles and a blank résumé. “My last job interview was eleven years ago,” reports 39-year-old Ben.

Recently, however, he’s rallied. Having completed a course enabling him to work as a home health aide, Ben has landed a job as the caregiver to Trev, a teen with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Trev needs help getting dressed and moving from his bed to his wheelchair, but otherwise he’s an average kid with a healthy libido. When he and Ben hang out at a local mall, they like to entertain one another with fanciful tales about the obscure sexual techniques they’d employ to please random female shoppers.

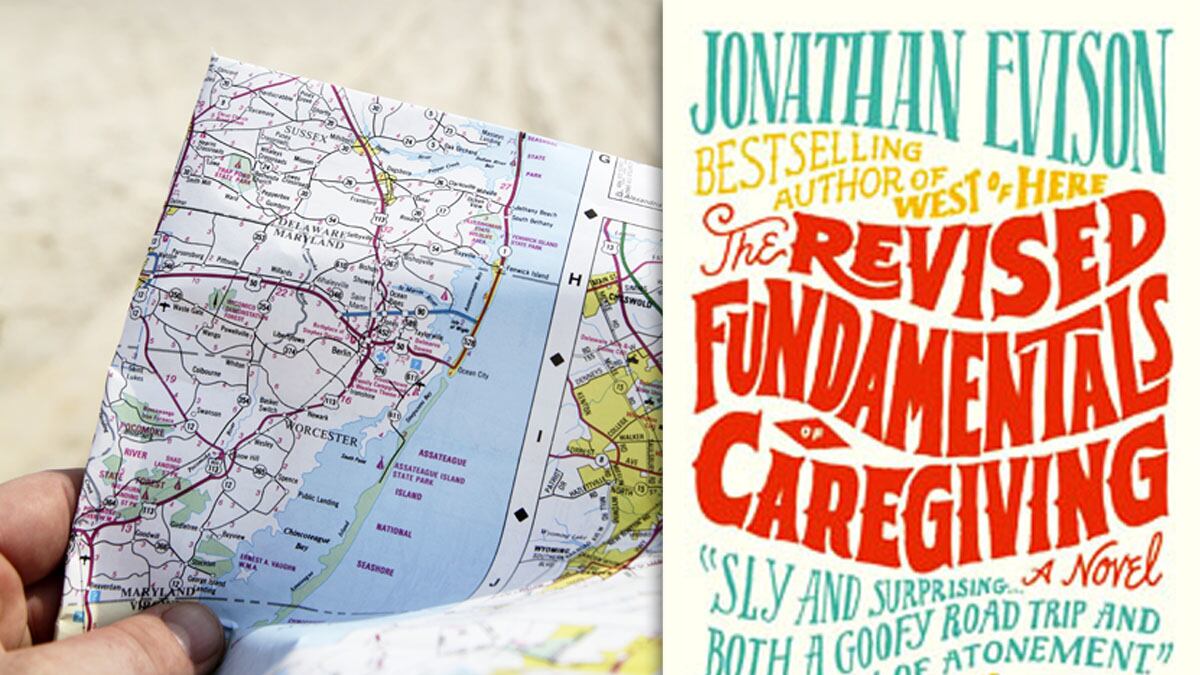

But what really bonds them is an unusual research project: a U.S. map that with the help of “a lot of Googling and pushpins” they’ve turned into “a sort of survey of North American roadside attractions,” like the Spam Museum, the stamp collection once owned by Hitler and the renowned Two Story Outhouse.

Amidst “all of this pinning and mapping,” Ben confesses to dread and hopelessness. Though he and his young friend appear to be in the early stages of planning a big road trip, Trev’s health, not to mention his own shaky state-of-mind, leaves Ben feeling like the very idea is a folly. “Needless to say, it’ll never happen and we both know it,” he says. “The map is just another exercise in hope. Next comes the slow, steady deferral of that hope over the coming months.” As it happens, Ben is wrong, and when he and Trev learn that the boy’s estranged father has ended up a in a far-flung hospital, they’ll soon have reason to embark on their long-deferred adventure. The journey is the first step in restoring Ben’s belief in himself and those he loves, and if he still hasn’t forgiven himself for his role in “the disaster,” it’s a start.

The novel’s problems can be easily spotted. As the narrative gains momentum, Evison relies on overly daffy set pieces, like the one in which Ben tangles with “a Yeti”—the brawl ends when Ben realizes that he’s biting the Yeti’s calf. He also has a weakness for schmaltz, and as a result, the reader occasionally has to grin and bear it when Ben says stuff like, “I never want to say good-bye to anybody ever again.” But this is a novel with a terrific sense of the relationship between comedy and tragedy—“It’s 10:31 a.m.,” says Ben, beer in hand, after his ties to Trev are temporarily severed. “I think I can smell the bottom from here”—and a winning cast of heroes and fools. Most important, it’s got a great, big heart, as exemplified by a scene toward the end of the novel when Ben finally realizes that his old life is over for good. “We haven’t got time for the Stonehenge replica at Maryhill, no time for the commemorative placard atop Sam Hill as we hurry west. And while I’m not sure what propels Trev onward, I know where I’m going, and I wish I could say it were home.”

The author of West of Here, a sprawling novel about Manifest Destiny and its reverberations, Evison again evinces a belief in healing and reclamation, recovery and renewal, through America’s big open spaces. In the process of unspooling the circumstances behind Ben’s pain, he pens urgent chapters about mortality, and about carrying on when life has its foot on your throat. He writes about coming to grips with the past almost as well as he does about loss. “In all the waking moments of my life,” Ben says, “the disaster is the one thing that ever truly happened. Everything else is a lie.” Or is it? As he presses on, the possibility of redemption appears in the distance, and it seems be getting closer with every mile of highway he and Trev put behind them.