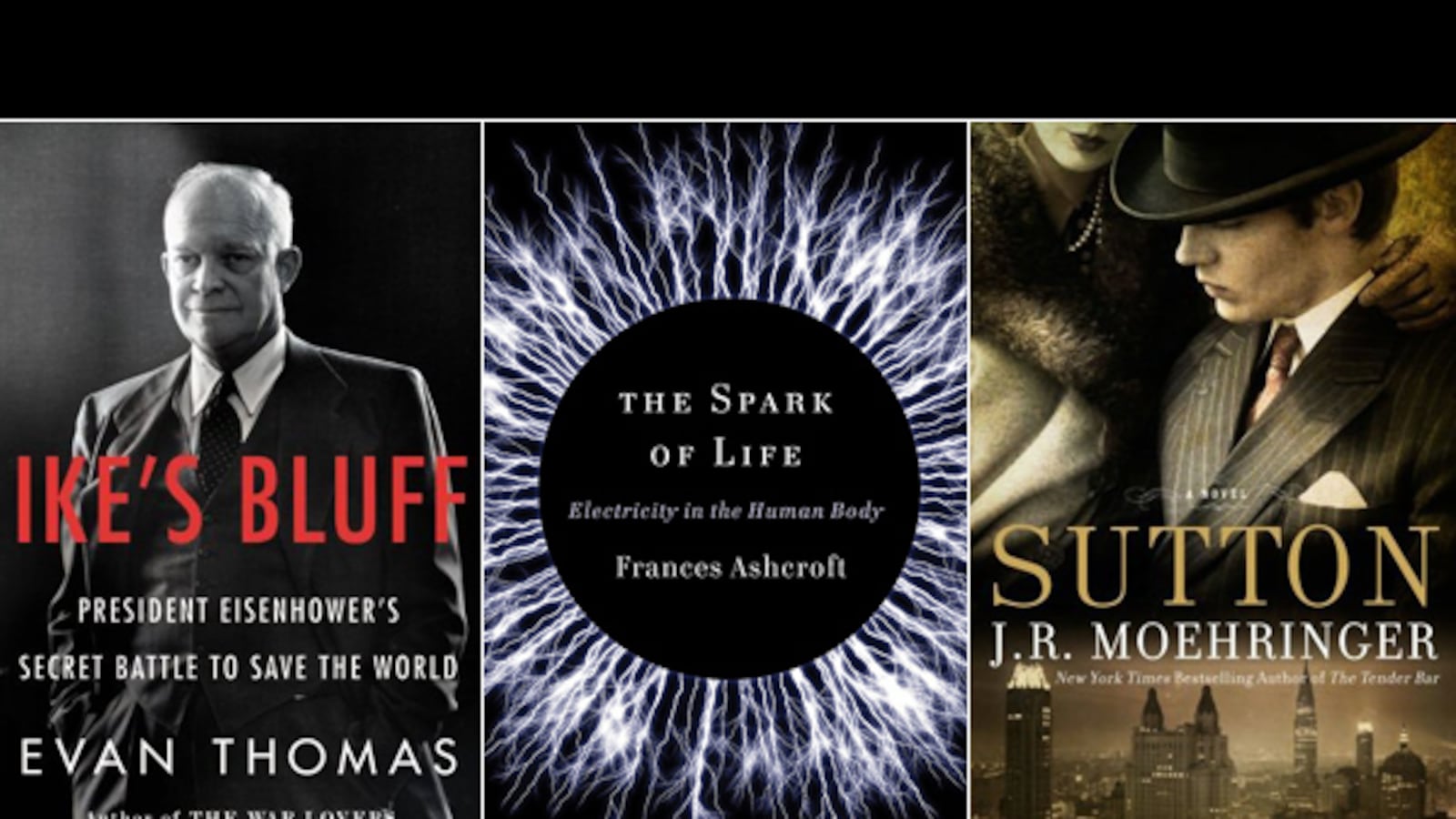

The Spark Of Life By Frances Ashcroft A scientist illustrates the power system of life.

You know you’re in for an interesting read when a book opens with a cautionary note warning you not to electrocute yourself (or any animals) if you happen to re-create the experiments within. Oxford professor Frances Ashcroft colorfully illustrates the fact that some of life’s most metaphysical concerns, such as fear, death, and thought itself, can boil down to the action of ion channels, which facilitate the movement of electricity through our bodies and brains. (The same mechanism controls our most basic processes, including the flexing of a muscle or the beating of the heart.) If the body is a machine, then this book is a users manual on the electrical system. There is some rigorous science here, along with charts and graphs that may give the reader stressful flashbacks to school exams, but Ashcroft writes for a large audience, and keeps things moving at a colloquial clip. There is an incredible weight of info here, beginning with a detailed history of the field, up though modern examples and advances being made pertaining to all matter of physical ailments. Just don’t go trying to cure them yourself.

We Have the War Upon Us by William J. Cooper With the threat of civil war looming, only compromise can save the Union.

This may be a divisive time in American politics, but none alive knows what it looks like when the government was really divided. In his new book, historian William J. Cooper (whose past work includes Jefferson Davis, American) details one of the most perilous periods in American history: the five months between the election of Republican Abraham Lincoln—who carried not a single electoral vote from a slave state—and the firing of the first salvo against the stockades of Fort Sumter in South Carolina. The narrative follows the congressional tumult that swirled around some familiar names from history class as well as the less familiar, like Kentucky Sen. John Crittenden, who served as a Cassandra to the coming war. The book reads like a Shakespearean tragedy played out on the national stage, where everything is converging toward a point of catastrophe, and the one thing that could avert disaster at the last minute (in this case, some kind of compromise) fails. Cooper makes the argument that “‘Anti-South’ provides a more accurate description of the republicans and their message than the narrower and balder term ‘anti-slavery.’” There are moral implications here, as well as historical.

Sutton by J.R. Moehringer On the first day of a famous career criminal’s release from prison, he is reintroduced into times that have passed him by.

Pulitzer Prize winner J.R. Moehringer’s first book, a memoir surrounding the tavern where he came of age entitled The Tender Bar, was heralded as a heartfelt and funny intersection of blue-collar realism and a deeper sensitivity. He brings the same aesthetic to his debut novel Sutton, in which he gives an account of Willie Sutton, bank-robbing man of the people, on the day he is released from jail on Christmas Eve in 1969. Sutton forces the young journalist who is lucky enough to score the first interview to travel with him to 14 points around New York, driven by a shaggy photographer straight out of Easy Rider. As they check off each location, a kind of This Is Your Life plays out in flashbacks. We see Willie grow into the career criminal that he became, have a life-long dance with the one that got away, and understand just how connected he is to a mysterious murder. (Part of the folk hero’s Robin Hood mythos is that he never hurt anyone.) This is the story of a misplaced archetype, a ’40s-style gentleman mobster released back into the wilds. In Moehringer’s more-than capable hands, the story has a life all its own beyond the historical fact.

The Canvas By Benjamin Stein Two interlocking narratives drive toward the heart of a mystery about memory and identity.

It’s rare that a book with an obvious gimmick isn’t, on some level, attempting to compensate for a deficiency that would glare more brightly under standard presentation, but luckily for Benjamin Stein, his new novel is far less experimental than it first appears. The book has two front covers, so that the reader can begin from either starting point and work his way toward the middle, each direction telling the story from the point of view of a different protagonist, First, Amnon Zirchroni, is a psychoanalyst in Zurich. The other, Jan Wechsler, is a publisher in Munich. For both men, their Judaism figures large in their lives, and in fact at the physical middle of the novel features a glossary of Yiddish terms that pervade the book. As the two stories close in on each other, a mystery develops around a potentially fabricated Holocaust memoir that echoes the real-life case of Binjamin Wilkomirski’s book Fragments, published in 1995. Although the bifurcated format is interesting for a minute or two, the best way to approach this book is to read alternating chapters of each character; in other words, like a standard narrative. And, really, there is no need for the distraction: this is a heady, distinctly German book with philosophical inquires on memory, identity, and language itself, and the complex plot should have had the confidence to stand on its own.

Ike’s Bluff by Evan Thomas How President Eisenhower averted disaster in the early days of the Cold War.

The experience of the 1950s in America was a paradoxical one: the country was at an idyllic height of prosperity and peace, while at the same time perched on the precipice of a new kind of war—nuclear war—that had the potential to leave the planet a smoldering wasteland. That the country was able to remain so stable in the face of such calamity was due in large part to the masterful statecraft of Dwight Eisenhower, the first man with the power to end the world. Historian Evan Thomas gives a riveting account of our 34th president’s geopolitical maneuvering in the first years after the world had been remade. The book focuses on Ike’s foreign policy, but it wasn’t only foreign factors that he had to contend with; at the time, there was a strain of military thought that held that preemptive strike was America’s only hope. Thomas’s mission is to replace the image of Ike as a grandfatherly war hero in over his head in the nuclear age with the image of a much more savvy, even Machiavellian player. As Thomas quotes Nixon on Ike: “He was a far more complex and devious man than most people realized … In the best sense of those words.” The book tells the kind of true story that pulp thrillers can only aspire to: egos at loggerheads, armies on high alert, and nothing less than the world at stake.