Sharp disagreements between senior Libyan officials over who was behind the U.S. Consulate assault in Benghazi are a sign of a “leadership deficit” in Libya that’s undermining the credibility of the newly elected authorities, diplomats and analysts warn.

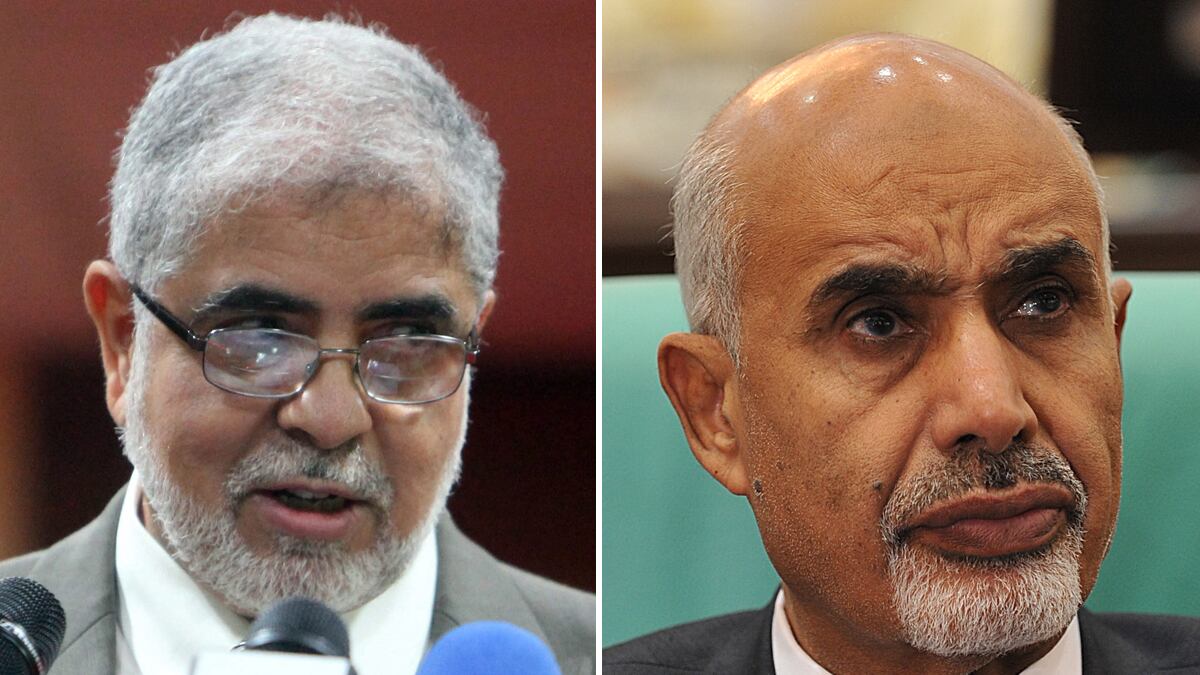

Frustration has been building as Libyan officials have vied to promote competing theories of what happened on the night of Sept. 11, when a mob stormed the poorly defended consulate, ostensibly in protest over an obscure anti-Islam film, leaving U.S. Ambassador Christopher Stevens and three other Americans dead. The office of Libya’s new prime minister, Mustafa Abushugar, says there’s no evidence of a preplanned al Qaeda plot and that all signs so far point to a protest that swung out of control when Libyan guards panicked and starting shooting, prompting fighters from the Salafist militia Ansar al-Sharia to return fire. The president of the recently installed General National Congress, Mohammed Magarief, often described erroneously in the international media as Libya’s president, says al Qaeda was involved and that the plot and attack involved “foreigners” from Algeria and Mali. Accounts of arrests also have differed.

“There’s a leadership deficit,” says Bill Lawrence, who directs the North Africa Project for the International Crisis Group. And fear is growing that the new Libyan authorities are squandering a chance to honor Stevens in the best way they could—by using the widespread public disgust at the death of the U.S. ambassador to start pressing the hundreds of armed revolutionary militias that have sprung up across the country to disband.

“This is a big crisis for the U.S., but it is an even bigger crisis for Libya,” says a European diplomat who declined to be named. “We have had months of deteriorating security, with Salafists attacking Sufi mosques, militias clashing, bombings of government buildings, and the assassinations of former security officials, and now this assault threatening Libya’s chances of a successful transition to stability. What we are getting from the leaders is a lack of unity and little direction.”

A sense of drift and disagreement has characterized the Libyan leadership’s response from the start. At a press conference, Magarief and the outgoing prime minister, Abdurrahim Abdulhafiz El-Keib, alternated between blaming the attack on “remnants of the former regime” and suggesting it was timed to coincide with the 11th anniversary of 9/11. Faced with criticism of the rampant lawlessness in the country and the weakness of the central authorities to curtail it in recent weeks, Libyan officials have reflexively blamed former Gaddafi officials.

The authorities were slow off the mark in launching an inquiry, which apparently didn’t start until the night of Sept. 12. A Libyan source describes panic in the hours after the attack, as officials in Tripoli and Benghazi scrambled to find out whether Stevens was alive and fielded calls from White House and U.S. State Department officials, and from the Libyan ambassador to the United Nations frantically trying to find out where Stevens was and whether he was safe. Initial reports were that Stevens was fine but had suffered a head injury, says a Libyan security source. “It wasn’t until about 3 a.m. [Libyan time] that we found out he was dead.”

Magarief’s blaming of foreigners and al Qaeda is greeted with skepticism from Libya watcher Peter Bouckaert, emergencies director at Human Rights Watch. “I would take his comments with a big bag of salt,” says Bouckhaert, adding that the GNC president would prefer the plot was a foreign one to distract attention from the authorities’ inability to combat homegrown lawlessness. “It is always so convenient to blame foreigners. More disturbingly, it shows that the new Libyan leadership still seems unable to come to grips with the problem it faces from well-armed militias that act out of their control and with impunity. That has been the problem for a long time, and they still seem unable to get their act together to deal with this grave threat.”

Even senior members of Magarief’s party, the National Front, are casting doubt on the direction he’s taking. “I don’t know what he is talking about,” says Abdul Rahman El Mansouri, a onetime exile and security adviser to the outgoing prime minister. “From the beginning there have been mistakes. I thought they shouldn’t have done that first press conference when they didn’t have any hard information. But I think they panicked and were as shocked when Bush first heard the news about 9/11. You have to understand this was really shocking for us. We owe Stevens a lot. He helped Benghazi during the rebellion when only God was there and we were on our own. If anyone can take credit for saving Benghazi, it was Chris.”

Mansouri disagrees with the idea that the Libyan leadership can’t pull together to “start pushing for the militias to disband.” But the lack of unity and confusion over roles and responsibilities of the prime minister and General National Congress president adds an element of uncertainty and echoes what happened before the July elections, when the National Transitional Council—which was replaced by the GNC—was at loggerheads with Keib and the ministers. The result was a lack of progress on major challenges, such as how to disarm and disband the militias and establish a national army, and practical matters affecting the everyday lives of Libyans, from garbage collection to maintaining roads and keeping the electricity on without frequent blackouts. Libyans became increasingly frustrated and were relieved to see the end of the NTC. In the few weeks since the GNC sat, it has earned scorn from Libyans for getting bogged down in debates about how much members should pay themselves.

One of the gravest dangers of the new authorities failing to progress quickly could be general frustration with a political process that isn’t delivering, leading to more recruits for the Salafists. Then, with security fragmented further, the militias, far from disbanding, would be further empowered as ordinary Libyans turn to them for protection.

On Monday night, Wanif al-Sharif, the deputy interior minister who was in charge of security in eastern Libya, was fired in the wake of the consulate attack, according to the Libya Herald. It wasn’t clear whether the firing was due to the failure of Interior Ministry forces—made up of other militias—to defend the consulate successfully or whether Sharif’s handling of the investigation was to blame.

Some diplomats in Tripoli have voiced concern that the U.S. is making a mistake in delaying the arrival of an FBI investigation team, which was due in Libya over the weekend but has been held back over safety fears. By the time FBI investigators arrive, it may be harder to get to the bottom of what happened, they say.