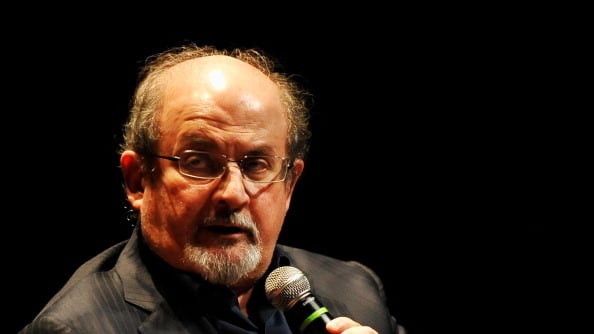

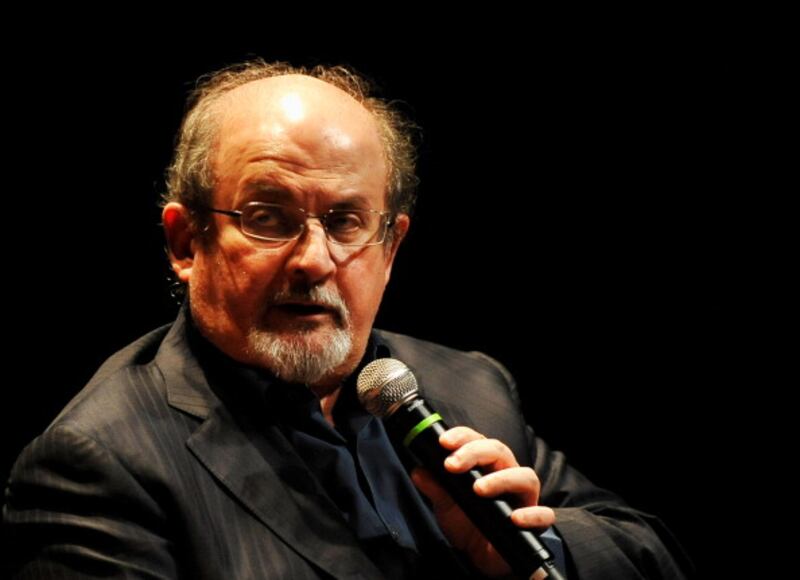

Amid anti-American demonstrations that roiled the Middle East, an Iranian religious foundation said on Saturday it was increasing its reward for the killing of author Salman Rushdie to $3.3 million. The British Indian novelist was, of course, famously sentenced to death in a 1989 fatwa by then-Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khomeini. Rushdie, who recently recounted the episode in the New Yorker, had supposedly blasphemed the prophet Mohammed in his critically-acclaimed book "The Satanic Verses."

But that was all a long time ago. Rushdie had nothing to do with the pseudo-movie that sparked the demonstrations. And Iran itself had little to do with the flames of anger erupting in the region. So why Rushdie—and why now?

The ruling clique in Tehran centers its calculations around the notion of political Islam, or Islamism. Tehran sought to delegitimize the Sunni monarchies in the Arab world though politicized faith. While Western observers might diagnose these Arab autocracies as illegitimate due to their lack of popular support and democratic institutions, the circle of revolutionaries around Ayatollah Khomeini favored a different argument: Arab monarchies are illegitimate due to their lack of Islamic foundations and deference to clergy.

The Islamic Republic sought to bridge the Arab-Persian divide and Sunni-Shia rift, helping Iran overcome ancient tensions with its neighbors in order to boost its claim for regional leadership, by leveraging Islamism. A frequent manifestation of the tactic has been Tehran’s anti-American and anti-Israeli rhetoric. Iran sought to focus the minds of the Arab masses on America’s presence in the region and support for regional dictators and on Israel’s occupation of Palestinian territory, as opposed to external powers’ ability to stoke Arab-Iranian and Shia-Sunni tensions.

But every user of a radical ideology as a tool of statecraft fears being out-radicalized. The very message of a new and radical belief system carries with it the risk of excess success—the ideology will not only win new supporters, it may also attract contenders for leadership of the new movement. The most acute risk comes from those who outflank radicals with deeper radicalism.

The Iranian regime's relationship with many of the Islamist movements in the Arab world are a matter of varying success. Shia power as the center of leadership made for an inherent flaw in the bid. Rather than becoming blind followers of Shia Iran’s regional aspirations, the recent visit of Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi to Tehran provided a preview of the pushback Iran is likely to experience. Having tasted power, the Arab Islamists are eager to lead, not follow.

In this context, the recent wave of anti-American demonstrations provided Iranian leaders with both an opportunity and a challenge. First, the anger sparked by YouTube trailer of an anti-Islamic film shifted the focus of the Arab masses away from the violence in Syria. Tehran sees this as a benefit, since its support for the Assad regime and his carnage of mostly Sunni Syrians has done immense damage to Iran’s soft power in the Sunni Arab world. With the YouTube clip, the Islamic Republic and the Sunni world once again found a common enemy, overshadowing their other differences. Keeping the flames of wrath alive further benefits the regime, decision makers in Tehran seem to believe.

But Tehran has rarely been content with passively benefitting from these crises. And particularly when passiveness can enable challengers to the leadership of political Islam to make headway. So, it moves piteously to remind the world that it was one of the originators of this movement by bringing Salman Rushdie back into the mix.

Rather than reclaiming leadership, though, Tehran comes across as an ideological power that has lost its touch, rehashing a decades old story in its transparent bid. While it upholds a veneer of pretending that the Arab spring has benefitted Iran, in reality the opposite holds true. Implicitly admitting this in private, Tehran's argument is that the picture will change once the Islamists win elections and take charge. At that point, resistance against Israel and America will become the regional priority, much to Iran's benefit.

There are many indications that Iran's investment in political Islam and the Sunni Islamists will fall short. The Islamic Republic is insisting on a formula that no longer resonates with the masses. Particularly with the Sunni Islamists, who couldn't care less about Salman Rushdie.