In the midst of a blizzard of confusing and contradictory polls (“Romney sinks far behind Obama;” “The president quickly loses his convention bounce”; “The race remains essentially tied, as it has for six months”) one unheralded recent survey suggests a decisive issues edge that could determine the final electoral outcome.

A Sept. 17 Gallup poll shows a commanding majority of Americans reject Barack Obama’s pitch that the people need a more activist government to solve the nation’s problems. By a margin of more than 2 to 1, the crucial independent voters say the government already tries to do too much. On a separate question, the representative sample of 1,017 adults shows an even bigger edge (6 to 1) for those who think the government wields too much power, as opposed to those who believe our elected officials and bureaucrats need even more.

Gallup’s been asking these questions for 20 years and only three times did Americans express a preference for bigger government: in the fall of 1992, just before Bill Clinton’s first presidential victory, early in 1993, right after the ambitious young president took office, and in October 2001, in the dark, desperate days following the 9/11 terror attacks. In the last 11 years, the desire for an expanded government role otherwise never matched the enduring distaste for a bloated state apparatus, not even during the financial collapse at the end of the second Bush term.

The careful wording of the question shows its power in exposing public attitudes: “Some people think the government is trying to do too many things that should be left to individuals and businesses. Others think that government should do more to solve our country’s problems. Which comes closer to your view?”

In the overall sample, 54 percent said government does too much. Only 39 percent wanted a more muscular, helpful state leading us “forward”—only 5 percent said they felt unsure or undecided in their perspective. Among independents, 62 percent identified with the small government side and only 29 percent wanted government to do more. Even among self-identified Democrats, 24 percent thought the government already gets involved where it has no business getting involved—raising potential problems for the Obama program of more “investment” and regulation.

Even more striking was the response to a related question: “Do you think the federal government today has too much power, has about the right amount of power, or has too little power?”

Just 8 percent of Americans say they want a more powerful government—51 percent said the government already possesses too much clout. The percentage holding that elected and appointed officials enjoy too little authority and influence has never gone above 8 percent in the history of the poll.

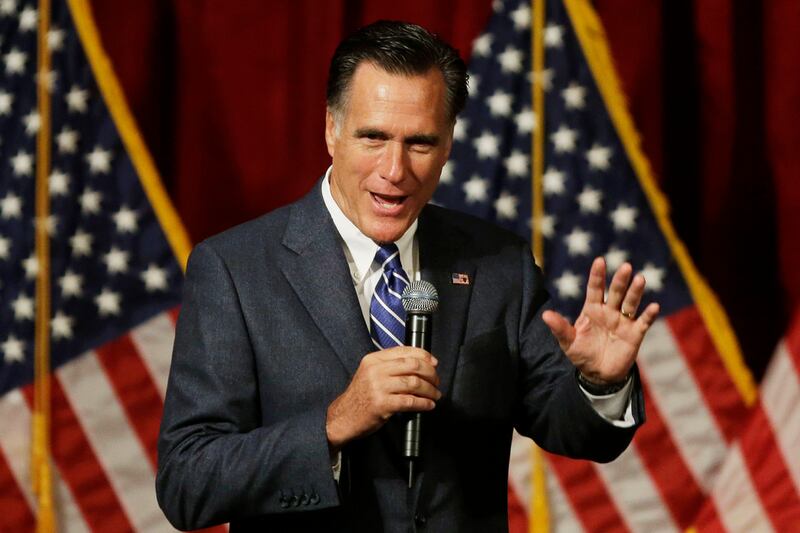

These attitudes, reflected in similar surveys by other public opinion organizations, show why President Obama remains so maddeningly vague about his agenda for a second term. Given the widespread dissatisfaction with current conditions (a sizable majority still sees the nation headed down the wrong track), he can’t simply offer more of the same, and the deep-seated distrust of an expanded government role suggests he’ll get scant traction by proposing sweeping new programs. Instead, he prefers to discuss Mitt Romney’s gaffes, tax returns, and purported inability to connect with ordinary Americans. He warns that Paul Ryan’s budget would devastate the middle class without laying out any scheme to assist a middle class already deeply devastated. The one concrete initiative he promotes most frequently involves raising taxes on the top 2 or 3 percent of income earners, without explaining how the extra money thereby secured (which amounts to less than 8 percent of the current yearly deficit, according to the administration’s own figures) would actually improve conditions for citizens of more modest means.

Rather than challenging the powerful public inclination against more expansive, activist government, President Obama deploys the rhetoric of compassion and assures voters in the most general terms that he will protect their interests and solve their problems. But doesn’t a president offering to “solve the nation’s problems” pledge precisely the sort of larger government role that most people—and huge majorities of independent voters—emphatically reject?

No wonder that Democrats spend their energy demonizing cruel, uncaring Republicans and suggesting that greedy tycoons like Mitt Romney (who, by the way, gave 30 percent of his gross income to charity last year) want to leave the less fortunate “on their own.”

In the upcoming debates, the challenge for Romney will be to force the president to get specific about how he intends to express the compassion he so frequently evokes—especially after four years in which poverty went up and middle class incomes declined sharply. The most important aspect of any presidency isn’t what the chief executive feels, it’s what he does. Doesn’t all Obama’s fine talk about lifting the downtrodden and protecting the vulnerable amount to the expansion of government that most Americans fear?

They feel that fear for a reason, since the more power exercised by government the less power and—autonomy—enjoyed by individual citizens. It’s no accident that we call our great national holiday “Independence Day”—Americans have always cherished independence, not just for the nation but for ourselves. The opposite of independence is dependence.

Rather than speaking about the 47 percent who pay no federal income tax (as he did, fatuously) Romney should highlight the one-third of all Americans (some 110 million of us) who now live in households that receive some form of federal welfare check—not including Social Security and Medicare, which are widely understood as pension programs to which working people contributed. Most of those who receive such benefits from Washington would, of course, prefer to stand on their own and to make progress in the free market—a fact that the candidate must emphatically acknowledge. He used a far better line on Friday than he has employed previously, promising that “in my administration, we’ll measure progress not by how many people get on food stamps, but how many people get off food stamps.” It’s not just the comfortable and the conservative who value the idea of independence.

In the climactic weeks of a ferociously competitive campaign, President Obama seems to enjoy a slight but consistent lead in most swing states but Governor Romney retains a huge advantage on the key issue of spending, prosperity, and the size of government. He doesn’t need to convince people that growing government is a bad idea. He merely needs to drive home the point that this sort of expansion has already occurred in Obama’s first four years, with vastly more intricate and intrusive regulation and spending in every corner of the economy, and there’s much more on the way if there’s a second term.

The simple question Romney must frame for the conclusion of this contest isn’t the Ronald Reagan formulation of “are you better off than you were four years ago?” It’s both deeper—and more decisive. The real choice is, do you want a government that’s bigger, more powerful, and more expensive, that tries to take on more tasks than ever before, in the name of addressing the nation’s challenges?

Fortunately for the Republicans, a clear consensus has already emerged on this issue, with the American people answering—strongly—in the negative.