Fifty years ago, John F. Kennedy made a historic decision, so quietly that almost no one but his secretary, Evelyn Lincoln, knew about it. In July 1962, President Kennedy asked a member of his Secret Service detail, Robert Bouck, to install taping devices around the Oval Office and Cabinet Room. Other presidents had experimented with recording—Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry Truman, and Dwight D. Eisenhower captured a small number of conversations on tape. But what Kennedy had in mind was an enterprise on a vastly different scale.

From that decision, invisibly, the presidency began to change. Beginning that summer, a huge number of his private conversations were recorded—248 hours of his meetings in the White House, and 17.5 hours of his telephone calls (recorded by a different system). The taping system was so secret that even top advisers like Ted Sorensen and Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., knew nothing of it. This was for the president’s ears only.

The result is a treasure trove for historians and for a public that still cannot get enough information about JFK. Here it is, raw and unfiltered, the everyday conversations of a president, his top staff, and an endless stream of visitors. There are moments of exultation and frustration, of nail-biting anxiety, and the normal banter that characterizes any workplace. Historians often fantasize about being a fly on the wall during the conversations of the past. Now we have that chance.

Kennedy never explained why he started taping, or how he intended to use his audio archives. It may have been to preserve a record of promises made—during the Bay of Pigs crisis of April 1961 his military advisers had assured him that the American-backed landings would succeed. But it is just as likely that Kennedy wanted the tapes for his own personal use, as a historian who had already won a Pulitzer Prize for Profiles in Courage, and as a writer who intended to write a memoir of his presidency someday. Kennedy often joked about this book on days when things weren’t going well—he sarcastically predicted that he would title it, Kennedy: The Only Years. In a sense, these tapes can be interpreted as a first draft toward that book.

For a year and four months, the tapes rolled, capturing the great deliberations of the Kennedy White House. We hear not only Cuban missile crisis, in second-by-second detail, but its long aftermath, in which JFK works to tamp down tensions with the Soviet Union. We hear the great civil-rights episodes of 1962 and 1963 happening in the present tense, at the exact time that President Kennedy and his brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, were shifting the might of the federal government behind the movement. We hear pained deliberations over the American war effort in Vietnam, where things were never going well and getting worse in the fall of 1963. There are countless human moments, when Kennedy loses his temper, or worries about rivals for the 1964 election (at one point he asks a colleague what he knows about a candidate named Romney).

Like most Democrats, Kennedy favored a loose management style that generated fresh new ideas. The result was a loud chatter coming out of the Oval Office, and it will be good for Americans, who have grown so cynical of politics, to hear these heated conversations from the boiler room of the ship of state. The Kennedy legacy continues to generate enormous interest, even a startling half-century after the fact. Thousands of books have been written about our 35th president, but one voice has always been missing from this cacophony—his own. These tapes go some distance to fill the vacuum. A president whose absence we feel to this day is suddenly there, viscerally present, in meeting after meeting. There are good and bad days; events were always moving quickly in 1962 and 1963, and no White House can ever completely control the news. But Kennedy is impressive—firmly in command of facts, challenging his advisers to do more, impatient with imperfect outcomes. There will always be Kennedy bashers objecting from the right, or the left, as they did when he was president. But the tapes offer something of value in a political environment that has grown dangerously toxic. They remind voters how much we ask of our presidents, and how much they give back to us, even when we disagree with them. They take a famous president off the pedestal where we place our former leaders, and put him right back in the arena, battling for what he believed in. In other words, they show us John F. Kennedy at the center of the action—exactly where he wanted to be. —Edward Widmer

Eavesdropping on the Joint Chiefs, Oct. 19, 1962

As the tape kept rolling, JFK left the room, and then his closest military advisers, General Maxwell Taylor and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, also left. That left several of the Joint Chiefs, unaware that the tape was rolling and recording their conversation.

There is no indication that JFK ever listened, but nevertheless, the very fact that their disrespectful conversation was captured constituted a chit for the president, well aware that the military had advised him disastrously during the Bay of Pigs.

David Shoup: You pulled the rug right out from under him.

Curtis Lemay: Jesus Christ. What the hell do you mean?

Shoup: I agree with that answer, General, I just agree with you, I just agree with you a hundred percent. Just agree with you a hundred percent. That’s the only goddamn… He finally got around to the word “escalation.” I just about [unclear]. That’s the only goddamn thing that’s in the whole trick. It’s been there in Laos, it’s been in every goddamn one. When he says escalation, that’s it. Somebody’s got to keep him from doing the goddamn thing piecemeal. That’s our problem. Go in there and frig around with the missiles. You’re screwed. You go in there and frig around with anything else, you’re screwed.

LeMay: That’s right.

Shoup: You’re screwed, screwed, screwed. And if some goddamn thing, some way, he could say, that they either do the son of a bitch and do it right, and quit frigging around. That was my conclusion. Don’t frig around and go take a missile out. [unclear] Goddamn, if he wants to do it, you can’t fiddle around with taking out missiles. You can’t fiddle around with hitting the missile site and then hitting the SAM sites. You got to go in and take out the goddamn thing that’s going to stop you from doing your job.

Earle Wheeler: It was very apparent to me, though, from his earlier remarks, that the political action of a blind strike is really what he’s…

Shoup: His speech about Berlin was the real…

Wheeler: He gave his speech about Berlin.

Lemay: He equates the two.

Wheeler: If we smear Castro, Khrushchev smears Willy Brandt.

Call to President Dwight D. Eisenhower, Oct. 28, 1962

With the Cuban Missile crisis unwinding, President Kennedy placed a round of relieved calls to all three living former presidents: Eisenhower, Truman, and Hoover. The calls with Truman and Hoover are relatively brief, but with Eisenhower (whom Kennedy addressed as both “Mr. President” and “General”), there was more time spent on strategy, including a surprising detour into the “goddamned mountainous country” of Tibet.

JFK: Hello?

Operator: Yes, please.

JFK: Oh, is the general on there?

Operator: I’ll put him on, yes, sir. Ready.

JFK: Hello?

Eisenhower: General Eisenhower, Mr. President.

JFK: General, how are you?

Eisenhower: Pretty good, thanks.

JFK: Oh, fine. General, I just wanted to bring you up-to-date on this matter, because I know of your concern about it. We got, Friday night, got a message from Khrushchev, which said that he would withdraw these missiles and technicians and so on, providing we did not plan to invade Cuba. We then got a message, that public one the next morning, in which he said he would do that if we withdrew our missiles from Turkey. We then, as you know, issued a statement that we couldn’t get into that deal. So we then got this message this morning. So we now have to wait to see how it unfolds, and there’s a good deal of complexities to it. If the withdrawal of these missiles, technicians, and the cessation of subversive activity by them…

Eisenhower: Yeah.

JFK: Well, we just have to set up satisfactory procedures to determine whether these actions will be carried out. So I would think that, if we can do that, we’ll be, find our interests advanced, even though it may be only one more chapter in a rather long story, as far as Cuba is concerned.

Eisenhower: Of course, but Mr. President, did he put any conditions in whatsoever, in there?

JFK: No, except that we’re not going to invade Cuba.

Eisenhower: Yes.

JFK: That’s the only one we’ve got now. But we don’t plan to invade Cuba under these conditions anyway.

Eisenhower: No.

JFK: So if we can get ’em out, we’re better off by far.

Eisenhower: That’s correct. I quite agree. I just wondered whether he was trying to, knowing we would keep our word, whether he would try to engage us in any kind of statement or commitment that would finally, one day, could be very embarrassing. Listen, suppose they got in, suppose they start to bombard Guantanamo?

JFK: Right.

Eisenhower: That’s what I’m getting at. I quite agree, this is a very, I think, conciliatory move he’s made.

JFK: Right.

Eisenhower: Provided that he doesn’t say that…

JFK: Oh, well, I agree. Oh yes, that’s right. I think what we’ve got to do is keep … That’s why I don’t think the Cuban story can be over yet. I think we will retain sufficient freedom to protect our interests if he…

Eisenhower: That’s all I was saying.

JFK: …if he, if they engage in subversion. If they attempt to do any aggressive acts, and so on, then all bets are off. In addition, my guess is that, by the end of next month, we’re going to be toe-to-toe on Berlin, anyway. So that I think this is important for the time being, because it requires quite a step down, really, for Khrushchev. On the other hand, I think that, as we all know, they just probe, and their word’s unreliable, so we just have to stay busy on it.

Eisenhower: As I’ve averred before, Mr. President, there’s one thing about … They, these people, do not equate, and I think it’s been a mistake to equate Berlin with Cuba or anything else.

JFK: Right.

Eisenhower: They take any spot in the world. They don’t care where it is.

JFK: That’s right.

Eisenhower: And it’s just the question is, are you in such a place you either can’t or won’t resist?

JFK: That’s right. Yeah.

Eisenhower: Now, when we got into Tibet. What is it with Tibet? Goddamned mountainous country over there, we couldn’t even reach it.

JFK: Right.

Eisenhower: And so, well, what could we do then was to reverse itself, that’s all.

JFK: Right, right.

Eisenhower: Now, so they get you, and they probe about when you can’t do anything. Then if they get another place where they think that you just won’t for some reason or other…

JFK: Yeah.

Eisenhower: Why, then they go ahead.

JFK: That’s right.

Eisenhower: So I think you’re doing exactly right on this one. Go ahead. But just let them know that you won’t be the aggressor. But on the other hand, then you’ve always got the right to…

JFK: That’s right.

Eisenhower: …determine whether the other guy is the aggressor.

JFK: Well, we’ll stay right at it, and I’ll keep in touch with you, General.

Eisenhower: Thank you very much, Mr. President.

JFK: OK. Thank you.

Private dictation, November 4, 1963

The mere fact that he recorded this dictation indicates that President Kennedy was upset by the events that had led to the overthrow of South Vietnamese President Diem and his brother, and by the faulty planning process that had allowed the coup to move forward. As he had done during the Cuban Missile Crisis, Kennedy paused to outline how an event of unusual historic significance had germinated and how the members of his top staff had felt about it. Midway through taping, he was interrupted by his son, which deepened the personal tone of his remarks, and the shock he expressed into the Dictaphone.

JFK: Monday, November 4, 1963. The … Over the weekend, the coup in Saigon took place, culminated three months of conversation about a coup, conversation which divided the government here and in Saigon. Opposed to a coup was General Taylor; the attorney general; Secretary McNamara; to a somewhat lesser degree, John McCone, partly because of an old hostility to Lodge, which causes him to lack confidence in Lodge’s judgment, partly, too, as a result of a new hostility because Lodge shifted his station chief. In favor of the coup was State, led by Averell Harriman, George Ball, Roger Hilsman, supported by Mike Forrestal at the White House. I feel that we must bear a good deal of responsibility for it, beginning with our cable of early August in which we suggested the coup. In my judgment, that wire was badly drafted, it should never have been sent on a Saturday, I should not have given my consent to it without a roundtable conference in which McNamara and Taylor could have presented their views. While we did redress that balance in later wires, that first wire encouraged Lodge along a course to which he was in any case inclined. Harkins continued to oppose the coup on the grounds that the military effort was doing well. There was a sharp split between Saigon and the rest of the country. Politically the situation is deteriorating. Militarily they had not had its effect. There was a feeling however that it would for this reason, Secretary McNamara and General Taylor supported applying additional pressures to Diem and Nhu in order to move them…

[John F. Kennedy, Jr., enters room]

JFK: Do you want to say anything? Say hello.

John: Hello.

JFK: Say it again.

John: Naughty, naughty Daddy.

JFK: Why do the leaves fall?

John: Because it’s autumn.

JFK: Why does the snow come on the ground?

John: Because it’s winter.

JFK: Why do the leaves turn green?

John: Because it’s spring.

JFK: When do we go to the Cape? Hyannisport?

John: Because it’s summer.

JFK: It’s summer.

John: [laughter] Your horses.

[John F. Kennedy, Jr., exits room]

JFK: I was shocked by the death of Diem and Nhu. I’d met Diem with Justice Douglas many years ago. He was a extraordinary character, and while he became increasingly difficult in the last months, nevertheless, over a ten-year period he held his country together to maintain its independence under very adverse conditions. The way he was killed made it particularly abhorrent. The question now, whether the generals can stay together and build a stable government, or whether Saigon will begin to turn on public opinion in Saigon. The intellectuals, students, et cetera, will turn on this government as repressive and undemocratic in the not too distant future.

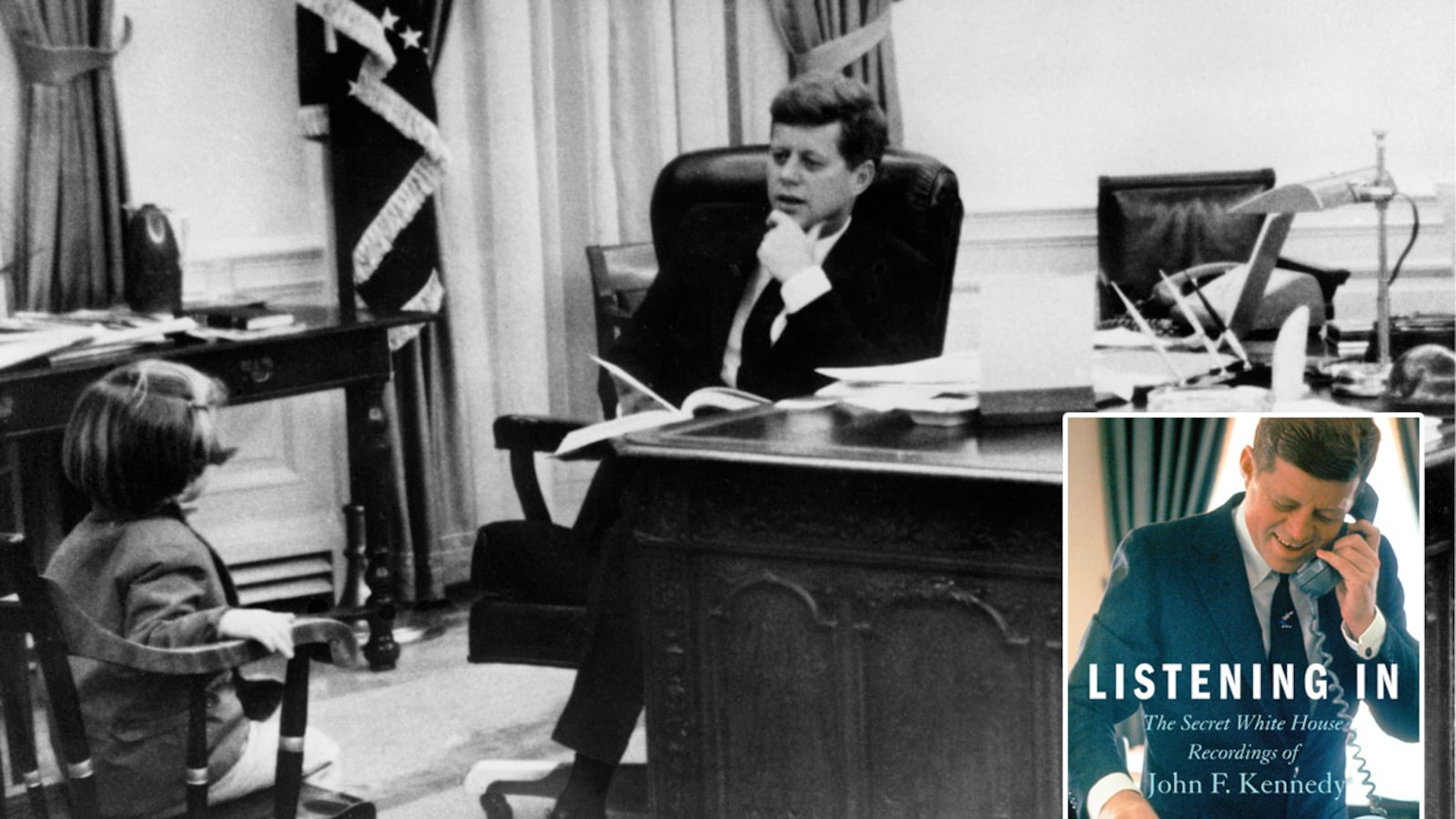

Excerpted from the book Listening In: The Secret White House Recordings of John F. Kennedy, The Kennedy Library Foundation; Foreword by Caroline Kennedy and Introduction and Annotations by Ted Widmer. Copyright (c) 2012 The John F. Kennedy Library Foundation, Inc. Published by Hyperion. Available wherever books are sold.