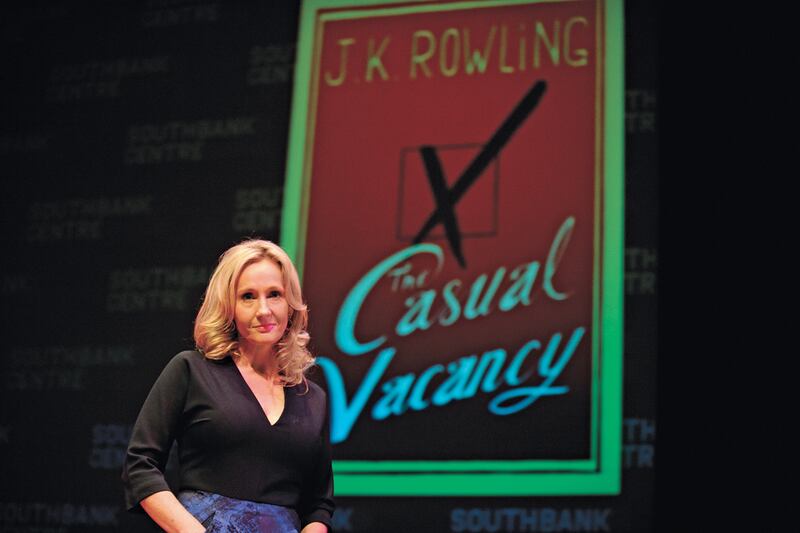

Considering that J.K. Rowling’s novel The Casual Vacancy took over the #1 bestseller on Amazon well before its official publication date of Sept. 27, it’s safe to assume that the first adult work by Harry Potter’s creator is about as review-proof as a book can get. Horrible or wonderful, it is already a runaway success.

Still, it’s an equally safe assumption that a lot of the eager readers who pre-ordered the book did so out of curiosity. Could the world’s most successful children’s-book author make it when she moved up to the grownups’ table?

I confess that I too approached The Casual Vacancy with that question uppermost in my mind. I was only a few chapters in before realizing what I should have known from the start: it’s much, much harder to write well for children than it is to write for adults, and for anyone capable of succeeding so brilliantly at the former, succeeding at the latter must have seemed like, well, child’s play.

ADVERTISEMENT

The only surprise is how dark, even bleak, this story is. But even that realization, upon reflection, is no surprise at all.

Let’s back up.

Rowling has written realistic fiction before, although most of us probably didn’t think of it that way at the time. Harry Potter and the Sorceror’s Stone, her first novel, opens in the real world. Before Harry discovers Hogwarts and the magical realm to which it belongs, he is living with his awful aunt and uncle, the Dursleys, and their equally awful son. The author brings this family to life with broad, satirical strokes, but alive they are in all their selfishness and pettiness. All too quickly, of course, they are supplanted by giants, wizards, magical buses, and flying brooms. But Rowling the realist made her debut long ago. We just weren’t paying attention.

Now fast forward to the present and The Casual Vacancy. To get some idea of its flavor, imagine a world without magic, beneficent protectors, or teenagers interested in anything more than themselves. Imagine a whole town populated and ruled over by Dursleys and a plot that takes most of its cues from The Book of Job and Murphy’s Law, where the strong look after themselves and keep their boots squarely planted on the necks of the weak. It is a novel that begins with a death and ends with a double funeral, and the 503 pages in between conjure a vision of life that is rarely more than nasty, poor, brutish, and short. Oh, and funny.

Make no mistake: The Casual Vacancy is a comedy, but a comedy of the blackest sort, etched with acid and drawn with pitch. Pagford, the fictional village in the west of England where Rowling sets her tale, is at first glance a storybook village stocked with a charming square, flower boxes bedecking every shop window, and a picturesque ruin topping the horizon. But that’s all veneer. Lurking not far beneath the prettiness lies the real Pagford—a dystopia that would take a wizard to set right. Absent magic, we get conniving politicians, close-minded scolds, flavorless marriages, and the occasional heroin junkie. Almost everyone we meet is wretched or miserable in some way or other. But extravagantly so—hence the comedy.

In the opening pages, village council member Barry Fairbrother drops dead from a brain aneurysm. The rest of the plot, in ways big and small, devolves from that occurrence. His opponents on the council immediately begin conniving to replace him with one of their own, the son, in fact, of Howard Mollison, the council’s blowhard chairman.

Rowling casts a cold eye on all of Pagford’s inhabitants, but she saves her cruelest descriptions for the loathsome Mollisons. We have hardly met Samantha Mollison, Howard’s 40-something daughter-in-law, before we learn that the “leathery skin of her upper cleavage radiated little cracks that no longer vanished when decompressed. She had been a great user of tanning beds when younger.” And Samantha, mind you, is the one Mollison for whom we actually muster some affection as the story goes on.

Rowling’s prose, muscular and serviceable, almost never gets fancy, although she could strip every simile from her sentences and the book would be the better for it. But occasionally her cruelty achieves a beauty all its own, as when she’s describing one of the three men vying for Fairbrother’s empty seat, a wife-beating, child-beating jerk who rounds out his monstrous profile with the occasional petty-theft at work: “There, in his poky office, Simon Price gazed covetously on a vacancy among the ranks of insiders to a place where cash was now trickling down onto an empty chair with no lap waiting to catch it.”

The feuding is not all political. Husbands and wives go at it behind drawn shades, and their spawn mimic the parents. Rich and poor despise each other, and all justify their meanness in the most appallingly self-serving ways imaginable. One teen teases a classmate to the point of cutting herself, drives his father to the brink of suicide, and sleeps with the teenaged daughter of a junkie just because he can. This poster boy of rationalization is particularly big on the notion of being authentic—until it proves inconvenient: “He had lately decided that questioning your own motives was inauthentic; a refinement of his personal philosophy that had made it altogether easier to follow.”

Viciousness in every imaginable variety is the norm in Pagford, right down to the language that spews from the mouths of its benighted citizens. Rowling, straitjacketed for so long by kid lit’s PG proscriptions, takes a palpable delight in the liberal use of the f-word and the c-word. It’s all a long way from the world of Harry Potter, but it’s hard to begrudge her a little unfettered fun, especially when she makes it so contagious.

There are however, similarities between the Rowling we thought we knew and the one met here. In both the Harry Potter series and this book, the villains are the most fully formed characters. We may not root for the Mollisons any more than we rooted for Severus Snape, but we are equally happy every time they appear. There’s an irresistible energy to their villainy that gives the story its propulsive drive. And as she did with the Potter books, Rowling proves ever dexterous at launching multiple plot lines that roar along simultaneously, never entangling them except when she means to. She did not become the world’s bestselling author by accident. She knows down in her bones how to make you keep turning the pages, no matter how old you are. And she is convincing. The dark vision at the heart of The Casual Vacancy may appall you, but it is not easily dismissed.

All it’s lacking is what would seem an all-too-necessary warning label: Keep Out of the Hands of Children.