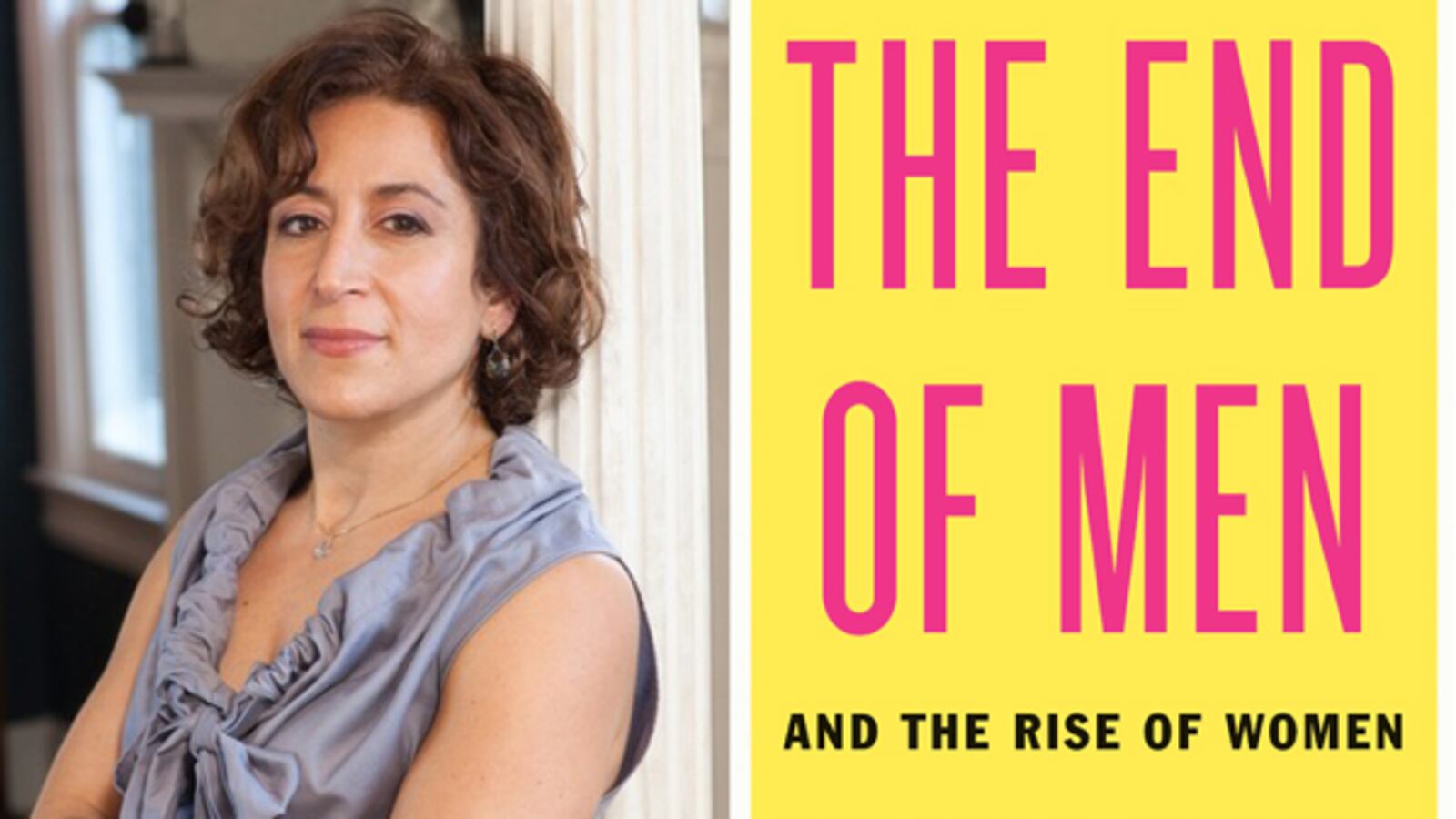

Last year, I responded to a survey on Slate that asked readers in marriages where the wife earned more money about their relationships with their spouses. The survey was conducted by Hannah Rosin, in connection with an article she was writing about “breadwinning wives.” The survey results were eventually incorporated into her bestselling book, The End of Men: And the Rise of Women.

If you haven’t read it already, The End of Men essentially argues that men in the United States (and pretty much everywhere else) are falling behind women in all facets of life. In school and in the workplace, women have made huge strides over the past few decades, while men have failed to adapt to the new economic and social realities that have obliterated “a power arrangement that’s prevailed for most of history.” Furthermore, according to Rosin, even as we men quickly ebb into marketplace obsolescence, those of us with families continue to be slacker manchildren in the home, unable to overcome sloppy parenting, haphazard home economics, and fealty to bro culture.

After I took her survey last year, Rosin contacted me directly, which led to an email exchange and then a long telephone interview in which I spilled my guts about my experience as a stay-at-home dad to toddler twins.

We spoke for over an hour about the joys and challenges of parenting, about perceptions of masculinity, about my relationship with my wife, and about my and my wife’s backgrounds. Among other topics, we discussed the fact that, despite growing up in a military family, I have parents who enthusiastically support the decisions my wife and I have made regarding our parenting roles. Likewise, my very traditional Vietnamese immigrant in-laws have no qualms with our domestic arrangements.

Rosin seemed surprised and impressed at this, yet she continued to press me for evidence to support her theory: marital tensions, awkward encounters with moms on the playground, feelings of shame at my own gender betrayal, and so on.

The reality: As I told Rosin, I’ve never been happier or more comfortable in my own skin than I have during my three-year stint staying home with my kids. I said there are moments of frustration and fatigue, of course, but when I consider how I feel about my place in the “new gender landscape,” I feel my life is a tremendous success.

Then I saw the book. Here’s how Rosin characterized our talk (as well as in a more recent Slate piece, “I Ain’t Sayin’ He’s a Gold Digger”):

... It was clear from my dozens of interviews that there are tensions under the surface. A power arrangement that’s prevailed for most of history does not fade without a ripple. In many cases I heard the same old marriage anxieties, only they showed up in the reverse gender. Andy, a stay-at-home dad in San Jose, Calif., had to cancel several appointments with me because he couldn’t get his twins to sleep. Before he stayed home with his kids, he was a carpenter. His wife is a physician, and because she makes so much more money it made sense for him to take the parenting lead. Andy likes watching the toddlers, but he is wistful about his old life, and somewhat defensive about his new one.The feelings flood over him when he passes construction crews while taking the twins on a walk: What would it be like to work with a group of guys up on a roof again? What adventures is his wife having while he’s wiping off bibs? When his wife and her doctor friends rib him about staying home, he over-aggressively pulls the manual labor card: “How about I come over and help you put that Ikea furniture together, Mr. Doctor?” It’s the old Betty Friedan identity crisis, only in masculine form. These days when his wife suggests that he should go back to work, Andy feels “terrified.” It’s been a long time, and he’s lost the stomach for the outside world.

I laughed out loud when I read this description of me. Despite our wide-ranging conversation about the richness of my life since I became a father and a fulltime caregiver, Rosin had rendered me as a hapless stock character in her tableau of post-masculine despair.

Let me make a few clarifications. First off, we live in San Diego, not San Jose, which probably doesn’t make much difference, except that it rains in San Jose sometimes, so maybe I would be depressed if I lived up there.

And if I’m “wistful” about my “old life,” it’s only because I was younger and stronger then, and my back didn’t hurt. Of course I have fond memories and endless stories of manly derring-do on the construction site, but these days I would far rather spend time with my kids than with a bunch of smelly knuckleheads who think there’s nothing funnier than to accuse one another of being gay all day long.

“Somewhat defensive” about my “new life”? Sure, on the extremely rare occasion that people make condescending or sexist remarks, I’ll call them out with a degree of aggression commensurate with the intent of their remark—just as I do if I hear denigrating generalizations about carpenters. Or teachers. Or doctors.

If I ever said that I was “terrified” to go back to work, I did so for laughs. I’m ambivalent about the inevitability of my going back to work full-time. After three years off, who wouldn’t be? But it’s not because I’ve “lost the stomach for the outside world”—I’m not in a monastery. I’ve been working part-time off and on throughout my tenure as a SAHD, doing small carpentry jobs on weekends and teaching the occasional college English class online or at night (Ms. Rosin didn’t mention that I moonlight as teacher). In my daily dad adventures I interact with more adults than I ever did as a carpenter.

The point here is not self-defense. I only mean to suggest that, if Rosin isn’t being flat-out manipulative in how she uses the stories she has collected to support her thesis and her snappy catchphrase, she is, at the very least, blinkered by her conviction that, no matter how comfortable a man may claim to be in the wild and wooly frontier of shifting gender paradigms, he is in fact miserable.

I was irked by this enough that the other day, I called Rosin to ask her why only the least positive elements of our interview made it into the book. She told me that she had included a 10,000-word chapter in an earlier draft she submitted, with thorough accounts of her favorite interviews from the dozens that she conducted. But, she told me, her editor had nixed that section because it didn’t fit in with the rest of the book.

We both ended up agreeing that the solution to the struggles of men is the loosening of gender expectations on all sides. Rosin acknowledged that even though she tends to focus on the “uncomfortable” aspects of every situation, she sees my own story, and the stories of other families who have eschewed traditional gender roles, as models for solutions to the man crisis.

That sounded good, and I understand that every bit of information can’t make it into a book, but the thesis of The End of Men is so broad that to leave out elements of research that refute the central argument—and Rosin and/or her editors did—is to remove the kind of nuance that lends it credibility. To Rosin’s credit, she does mention in the book that, based on the results of her multiple-choice poll, men and women in “seesaw marriages,” where economic pragmatism overrules gender roles, overwhelmingly report happiness and stability. But she quickly moves on and focuses on anecdotal nuggets that portray men as sad, angry, or of dubious competence.

Some critics have called The End of Men a misandrist book, and it’s a claim that’s hard to dismiss when you read generalizations like this: “When it comes to the knowledge, drive, and discipline necessary to succeed, women are the naturals with whom men have to strain to keep up.”

While reading the statistics and anecdotes Rosin uses to illustrate men’s downward spiral, I couldn’t shake the feeling that these laments were tinged with schadenfreude. In her conclusion, Rosin offers some faint glimmerings of hope for us, but throughout the body of the book, men are portrayed as a lost cause. Instead of searching for ways to level the playing field, she seems to accept that women’s achievements must come at an exorbitant price to men.

Following our more recent conversation, I feel I want to give Rosin the benefit of the doubt, and despite her inaccurate and unflattering portrayal of me, I still hope a lot of people read this book. Because she’s right: the ground is shifting in terms of gender equity, and while we should celebrate the leaps women have made toward an egalitarian society, we can’t just watch helplessly as boys get left behind in school, and men struggle to maintain their footing in the working world.