Midway through Salman Rushdie’s memoir of his life under the fatwa, Joseph Anton, the beleaguered novelist reflects on those books and movies that had filled his childhood. Of The Wizard of Oz, he notes, “the two great themes of the film were home and friendship.”

Home and friendship are the themes not just of Joseph Anton, but all of Rushdie’s work: novels and stories, essays and reflections about how the world of childhood morphs from magical remembrances into the everyday reality of adult life. Home and friendship, too, are the themes of all great works of literature, whether for children or adults: the novels of Charles Dickens, the tales of Mark Twain, the narratives of Toni Morrison, and, indeed, the Harry Potter books of J. K. Rowling.

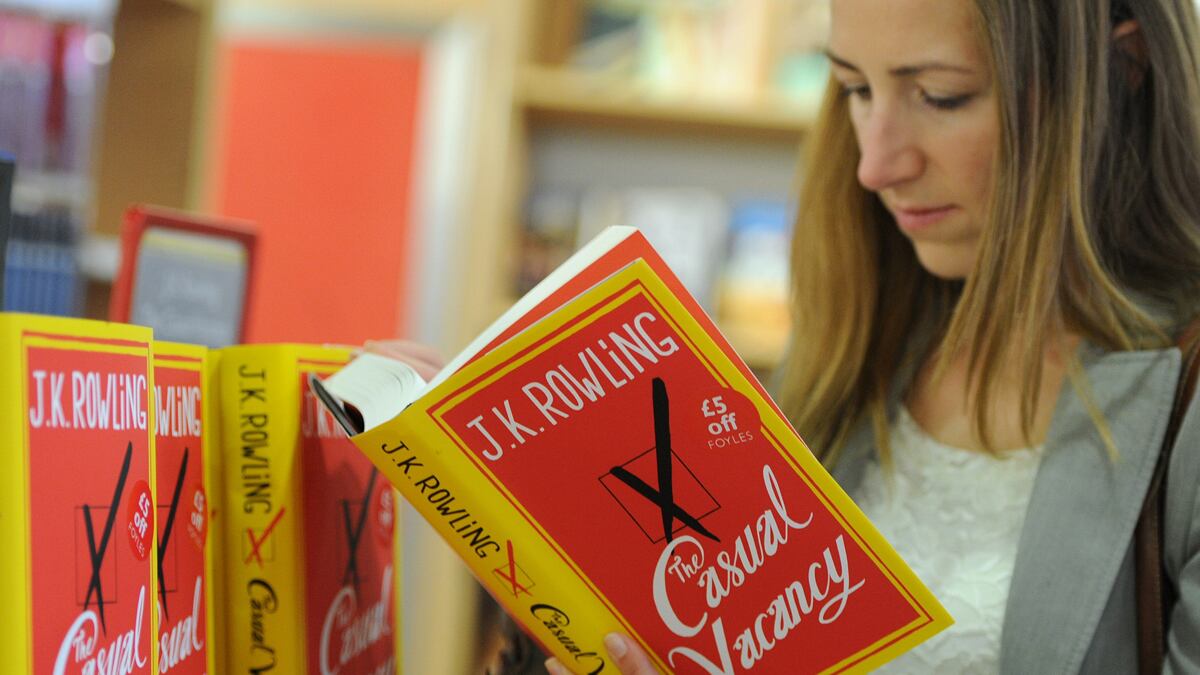

Rushdie’s Joseph Anton and Rowling’s The Casual Vacancy, released within a week of each other, challenge us to ask: what is the place of childhood in the adult world; what happens when a writer turns from young to grown up readers, and from adult themes to children’s entertainment; what do we expect from our writers, and what happens when they disappoint us?

Many readers came to Rushdie’s book expecting personal confession or contrition, or a deep reflection on the writer’s life in a politically charged world. They got that, but they got it colored by a distancing, third-person narrative and bouts of self-justification. Many readers, too, will come to J. K. Rowling’s novel for adults expecting the prose wizardry of Harry Potter. Will they be disappointed?

Harry Potter was a brilliant achievement. It blended the coming-of-age story, inspired largely by Dickens, with the magical wonders of Tolkien. Most children read the books for their excitement. I read them for their literate lessons. In Harry Potter, the true wizardry went on not in the forest or the playing field, but in the classroom and the library. Wizardry was but a heightened form of literacy: a way of reading recipes and of reciting spells. Harry Potter’s is a world of books, and the stories got young people reading not just because they were interested in the plots or characters, but also because the very lesson of the books was to read books themselves. Home and friendship were defined by what was on the bookshelf and who shared your readings. Hogwarts was a place of shared belonging, poring over textbooks, rooting through the library, and finding peers among the paperwork. The Dursleys' home, by contrast, was a place of isolation, as Harry can only read alone, buried under the bed sheets.

After all of this magic, what could we have expected? The Casual Vacancy may be a disappointment, but it is a natural one. For after having written books of magic for a magical age, Rowling has come out with a book of Muggle life for Muggles. Is this what happens when you grow up? Do we leave behind the thrills of a Dickensian adventure for the ordinary evenings of a small town’s politics? Do we abandon David Copperfield or Great Expectations and grow up to live in the novels of Anthony Trollope? After all of the adventures at Hogwarts, Rowling may be saying, all you want to do is snuggle up with a cup of tea and a vicar.

We may believe that she has let us down; but maybe we have let ourselves down, too. Unlike the Hogwarts students, the adults who populate the Pagford of The Casual Vacancy (and so many of our own towns) are not readers. They do not ride into imagined worlds; they do not fill their lives with books. The conflict of the novel hinges on competing institutions: a public housing project and an addicts’ clinic, the former a faceless block of living spaces, the latter a hospital for those who tried to escape them. In a world without books, there are only drugs. The potions of Hogwarts had their narcotic effect, but for the children who came back to read Harry Potter again and again, the addiction was to words.

Among the novel’s characters—Barry Fairbrother, Howard Mollison, Krystal Weedon, and a host of evocatively named others—the only one who could be said to have a truly inner and imaginative life in the novel is the troubled young Krystal: living in the projects, a bit of crystal in the weeds. Only here will readers of the novel find a fully interiorized life. Only here will readers find a level of prose that aspires to literary fiction. “Fear fluttered inside Krystal’s belly like a fetus.” Not bad, and even better, too, is the extended passage in parentheses that charts the workings of her fears, with the parentheses themselves marking these paragraphs like stream-of-consciousness reflection. And yet, even Krystal has her troubles with the written word. Looking at the signage at a bus stop, she pauses. “Krystal did not read well; being confronted with large quantities of words made her feel intimidated and aggressive.”

This moment in the novel seems to be its turning point: a damning statement about what it means to be functionally illiterate. Surely, the children and the teens who lapped up the hundreds of pages of Harry Potter were hardly intimidated by large quantities of words. And surely Hermione Granger was hardly put off by the kinds of signs that anger Krystal: “line upon line of impenetrable print, with words as long as Krystal’s arm and arrows pointing left, right, diagonally.” It is as if, here, in this all-too-Muggle world, a young girl cannot face the enigmas of writing, as if the bus-station sign becomes a potion or a cryptogram, as if she cannot transport herself out of this sad space, with its diagonal arrows, into a magical Diagon Alley.

Perhaps that, too, is Rowling’s dilemma. For having trapped us on an ordinary street, she does not have the words to lift her characters to inspiration. This never was a problem for Rushdie, who has moved effortlessly between writing for adults and writing for children. Haroun and the Sea of Stories grows out of the magical realism of Midnight’s Children. Joseph Anton itself begins with one of the most affecting remembrances of a father’s powerful, and powerfully ambivalent, legacy. What Rushdie realizes is that, in the end, all readers become children when led by the hand of a great writer. Dickens knew that in David Copperfield (as much an influence on Midnight’s Children as any lived experience of India). At the start of that novel, the young David finds himself in his late father’s library, and reading the adventures of Tom Jones, Don Quixote, and Robinson Crusoe his imagination is kept alive. “I had a greedy relish,” he recalls, for stories, and he looks back on his time in the library, “reading as if for life.”

Without such reading, there can be no life, and it seems to me that the real vacancy, casual or otherwise, in Rowling’s novel is the book itself. Home and family can give us fair brothers. But only the literate imagination can bring them back to life.