Too Good to Be True By Benjamin Anastas A novelist in financial ruin digs himself out with the help of the love of his son.

Benjamin Anastas was living a young writer’s dream. A graduate of the fabled Iowa Writer’s Workshop, his 1998 novel, An Underachiever’s Diary, had been well received by the right people, and he had begun to make for himself the creative existence that he had always hoped for. But Too Good to Be True wouldn’t be a good memoir without a catastrophic downfall. Because of mutual infidelities, his marriage collapsed in its infancy and his wife decamped with another man while still pregnant with Anastas’s son. Artistic and financial death soon followed. In this taut memoir, Anastas writes about his admittedly colossal failures and the myriad indignities of poverty, such as what it feels like to be pursued at all hours by debt collectors or having to pay tribute to a Coinstar machine just to buy food for your son. The train wreck (and it is a grisly one) isn’t the only compelling thing here, however, since Anastas can craft a world-class sentence. The love he has for his child shines through, and it saves him as he scrabbles to regain his footing. This book is not necessarily guaranteed to destroy the ambition of every aspiring writer who reads it, but it probably will. Just keep two things in mind: don’t run up credit-card debt, and don’t cheat on your significant other unless you really mean it.

The Fifty Year Sword By Mark Z. Danielewski A poetic, avant-garde "ghost story for grownups."

When only a thousand copies of The Fifty Year Sword were released in 2005, they became quite valuable to fans of the avant-garde author of House of Leaves. It’s now in a wider release, and the book tells a “ghost story for grownups.” An odd party of five orphans and their attendants are assembled for a birthday celebration on an East Texas ranch. Soon they are visited by a dark presence carrying a mysterious box, who announces that he is “a bad man with a very black heart.” He lapses into a tale about his journey across a landscape that is half fairy tale, half nightmare, in order to find a strange and powerful weapon to aid him in an unspecified revenge. The story might be childish if it weren’t refracted through a complex and challenging form. Danielewski uses experimental typography, elliptical descriptions, and color-coded parentheses. The latter is needed because the story is told in the voice of the five grown-up orphans, who simultaneously remember what the figure relay to them. It is a bit confusing, but of little consequence really, as the book is not about the story on the surface; like the most affecting ghost stories, the real weight comes less from the spooky plot points and more from the elements of reality that take place in the minds of the characters: the depression, anger, and jealousy that are hardly supernatural, or even fanciful.

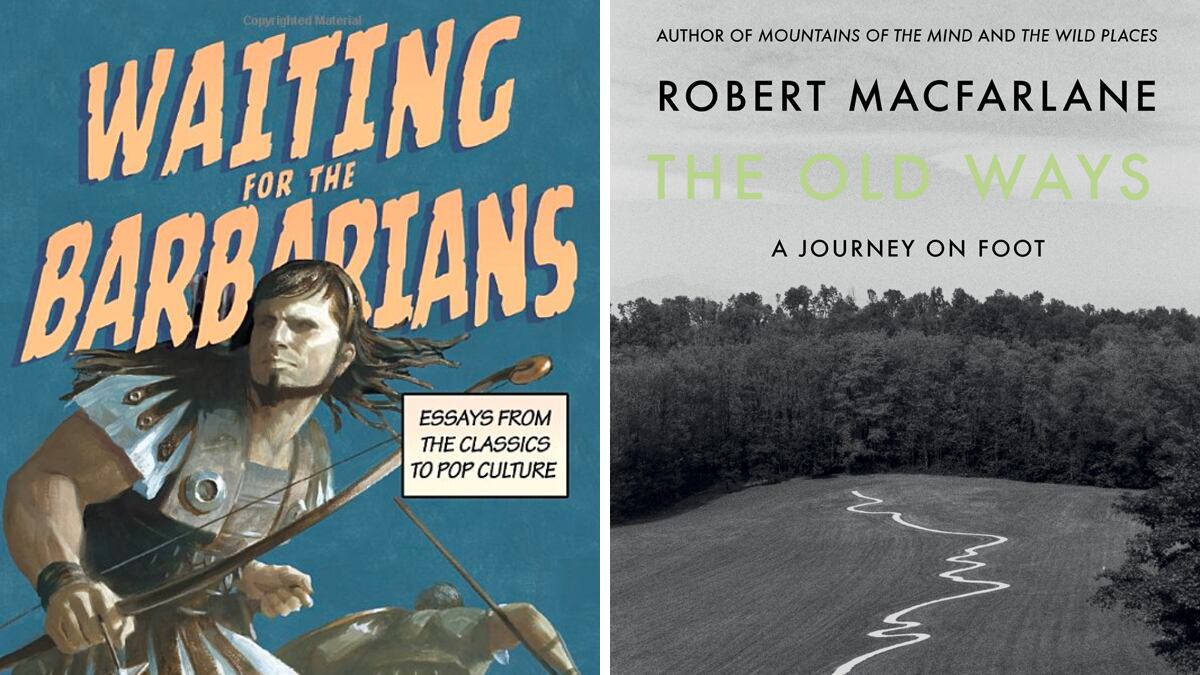

Waiting for the Barbarians By Daniel Mendelsohn A master classicist takes on subjects from the ‘Iliad’ to ‘Avatar.’

It is the mark of only the most compelling criticism that it can leave the reader feeling edified even if they haven’t seen, read, or listened to the cultural artifact being criticized. The new collection of essays by Mendelsohn, Bard College professor and contributor to The New Yorker and The New York Review of Books, does just that. Mendelsohn’s work is absolutely vital in both senses of the word—it breaths with an exciting intelligence often absent in similar but stodgier writing, and it should be required reading for anyone interested in dissecting culture, or who simply find themselves thinking about the complex flaws of an almost-good movie a week after leaving the cinema. In the book, his scope includes both the high- and middlebrow. Subjects range from the classics and the poetry of Rimbaud to James Cameron’s Avatar and Julie Taymor’s disastrous staging of Spider-Man on Broadway. Mendelsohn also has a laudable contrarian streak, which he displays in a brilliant essay that might give the reader reason to rethink some of the reflexive praise heaped on AMC’s Mad Men. Taken together, the collection offers a sort of defense of the modern age of culture. If a true-blue classicist can engage with the current zeitgeist using the full weight of his intellect and without an iota of demoralization, than the rest of us have no excuse.

The Noughties By Ben Masters With their uncertain futures looming, Oxford students do what their generation does best on the eve of graduation.

Graduating from college can be one the most sundering experiences in a young middle-class person’s life. In his debut novel, the Englishman Masters captures the stress of the event as it affects a group of Oxford students on the night before they graduate, told from the point of view of English literature student Eliot Lamb. As Eliot and his mates move from bar to pub to club, which are the titles of the book’s three sections, their last four years are replayed via flashback, and Eliot attempts to wrap up his loose ends, romantic and otherwise. Masters is 25, and his book is the work of a young man for better and for worse. He has captured the idiom and universe of his subjects perfectly, centered mainly around partying, alcohol, and the crude mode of communication that is the text message. But his enthusiasm for producing purplish phrases (“We are quotidian calamities; unwitting lyricisms; veritable wordsmiths out on the razz, lugging twentieth-century regret on our backs”) could be more restrained the next time round.

The Old Ways By Robert Macfarlane A journey both inward and outward along the old roads of England and beyond.

Walking and thinking have long gone hand in hand. There was peripatetic Aristotle, or Keat’s walk along the River Itchen that inspired his poem “To Autumn,” and it’s said that Kant’s daily stroll through Königsberg was so reliable that the townspeople would set their clocks by his appearance. Macfarlane has taken the tradition of contemplative strolls to the extreme, as he sets out on foot to crisscross the ancient pathways of England and the environs beyond. The book is an interesting blend of forms, part cartography, philosophy, travelogue, and poetry. But Macfarlane’s lyricism keeps things bound together: “As I envisage it, landscape projects into us not like a jetty or peninsula, finite and bounded in its volume and reach, but instead as a kind of sunlight, flickeringly unmappable.” And although the solitary pleasures of a (very) long walk would seem to suggest a kind of hermeticism or solipsism, this isn’t the case; Macfarlane is more than happy to share the road with fellow wanderers.