In this age of email, text messages and social media, are authors still writing letters?

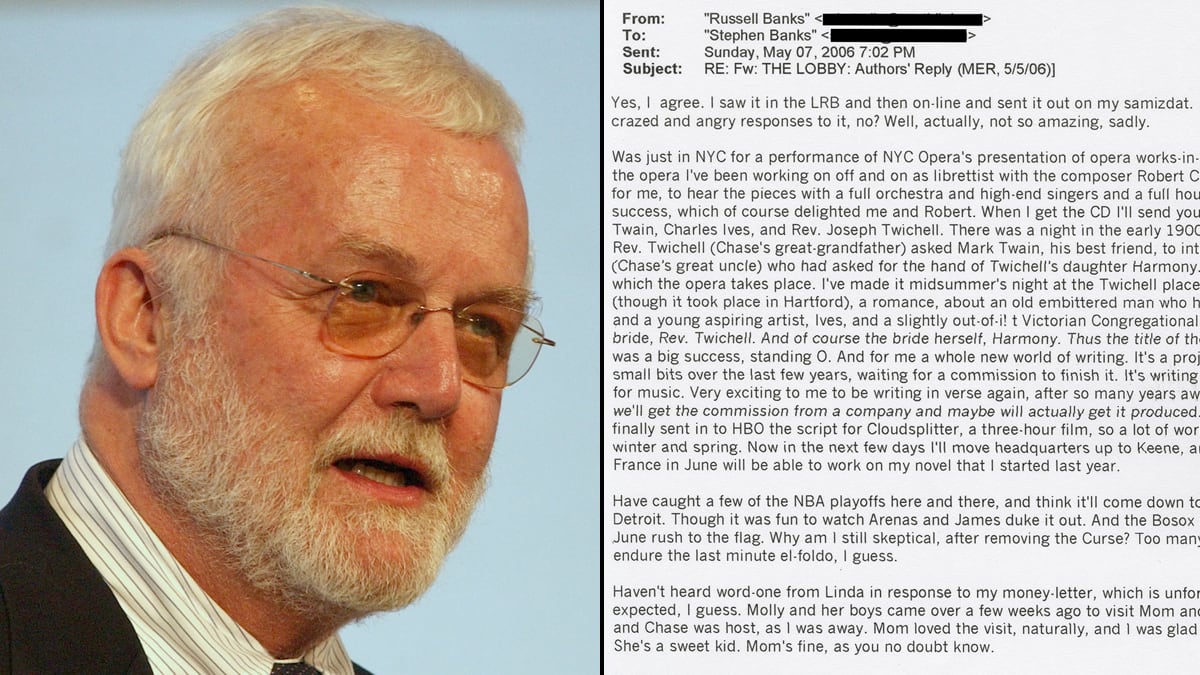

The correspondence of Russell Banks and his brother, Stephen, beautifully illustrates the transition of letter writing in the digital age. In more than 45 years, the Banks brothers exchanged hundreds of missives. (The tranche was recently acquired by the Harry Ransom Center, where I work.) The letters of the two-time Pulitzer Prize finalist (for his novels Continental Drift and Cloudsplitter) are thoughtful, intimate, and voluminous. Topics addressed range broadly, from his early struggles as a writer and his establishment of the literary journal Lillabulero, to his travels, hobbies, and, of course, his novels.

Many of these are handwritten in Banks’s neat and steady script, or they are lengthy, typewritten notes. Yet more than two-thirds of this correspondence is in the form of email. Between 1964 and 1995, Banks sent 108 letters and postcards to his brother. Yet from 1995 to 2011—in roughly half the amount of time—he sent his brother more than 225 emails. In a 1994 letter, Banks wrote of email: “I just started using it and find it a fast and easy way to stay in touch with lots of people I’d otherwise write to only once in a while.”

Email correspondence is becoming more prevalent in writers’ archives at various research libraries. They can be found in Salman Rushdie’s papers at Emory University and Harold Pinter’s letters at the British Library. As with Banks’s correspondence, emails generally coexist with traditional letters in an author’s archive. Some emails are transferred to libraries as digital files. Banks’s emails to his brother are all printed on paper, but many of the more recent ones were also saved on disks.

Traditional letters are of course growing scarcer. Young writers who grew up with the technologies of email and cell phones and who are now embracing other electronic forms of communication and social media have not yet placed their archives at research libraries, so we don’t know what their correspondence will look like and how much of it will actually exist. As we see with Banks’s emails, the convenience and pervasiveness of electronic communication offer some hope that the volume of correspondence may in fact be on the rise.

But the writing of an email is a very different process from the crafting of a letter. Will the informality and brevity so characteristic of email communication compromise the quality of writers’ correspondence?

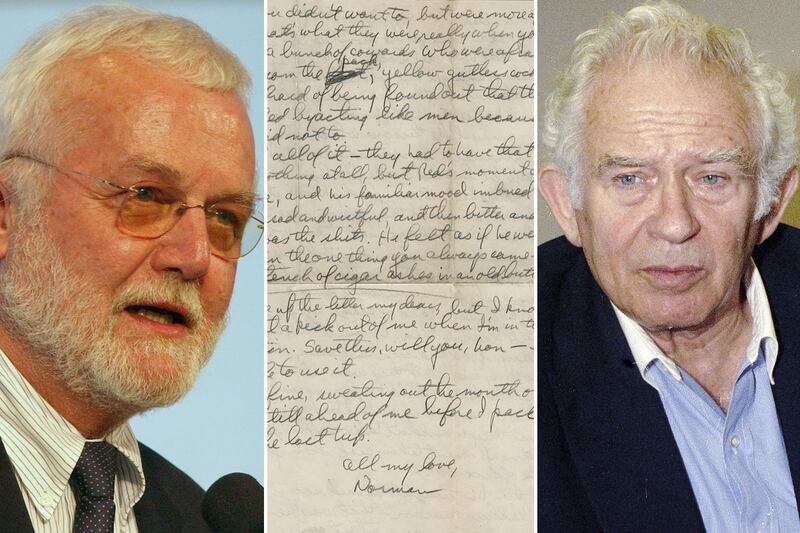

Some authors have elevated letter-writing to an art—you only have to read Words in Air: The Complete Correspondence Between Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell for evidence. Russell Banks’s emails are now carefully preserved alongside his papers, in the same stacks that hold more than 75 boxes of manuscripts of his work. Nearby, Norman Mailer’s letters fill 223 boxes, and those of British playwright Arnold Wesker fill more than 100 boxes. There are wonderful examples of James Salter’s poetic letters, as well as correspondence by Julian Barnes, J. M. Coetzee, Denis Johnson, Tim O’Brien, and Jayne Anne Phillips, among dozens of others. Although there is not much correspondence among his papers, the late David Foster Wallace was a gifted, prolific letter writer who also corresponded by email. (An important cache of his letters can be found in Don DeLillo’s papers at the Ransom Center.) These letters feature Wallace’s unique voice and reveal some of the struggles he faced with his writing. As D.T. Max’s recently published biography of Wallace reveals, other collections of Wallace’s letters remain in private hands. Let’s hope that many of them will be preserved at research libraries in the years to come.

Correspondence is so valuable because it provides a window into a writer’s world—into the private thoughts and day-to-day activities that fill a writer’s life—often yielding new information about authors, their influences, and the creative process. Kurt Vonnegut, whose correspondence is due for release at the end of the month, saved copies of letters he’d sent and received even during his earliest years as a writer—until a fire destroyed them on Jan. 30, 2000. Ernest Hemingway's correspondence is expected to swell to a staggering 12 volumes. The third volume of T.S. Eliot’s letters were published last month. Samuel Beckett's correspondence is slated for four volumes. The care and time that many of the great 20th-century modernists devoted to their correspondence in that golden era of letter-writing hints that they may have had one eye fixed on posterity, knowing that all of their writing would be read after they die—letters, diaries, even grocery lists.

It is clear that we will see published volumes of writers’ emails. The tweets of Salman Rushdie or Colson Whitehead—who has even released fiction via Twitter—might someday find a home in books. And who knows what future modes of communication await us?