The Japanese telecommunications giant Softbank announced Monday that it was taking a 70-percent stake in the troubled U.S. wireless company Sprint. The company’s shareholders will get $12.1 billion and Softbank will raise another $8 billion to finance the $20 billion deal. Sprint, whose market share has been falling steadily, will get a giant cash infusion that will allow it to build out its advanced LTE network and possibly acquire more rivals.

This marks the largest Japanese acquisition of American company in more than 30 years. But it also marks an important cultural shift. In stark contrast to the 1980s, when Americans feared Japanese capital, the Softbank investment hasn’t raised many hackles. And the deal bears testimony to a larger shift in global finance.

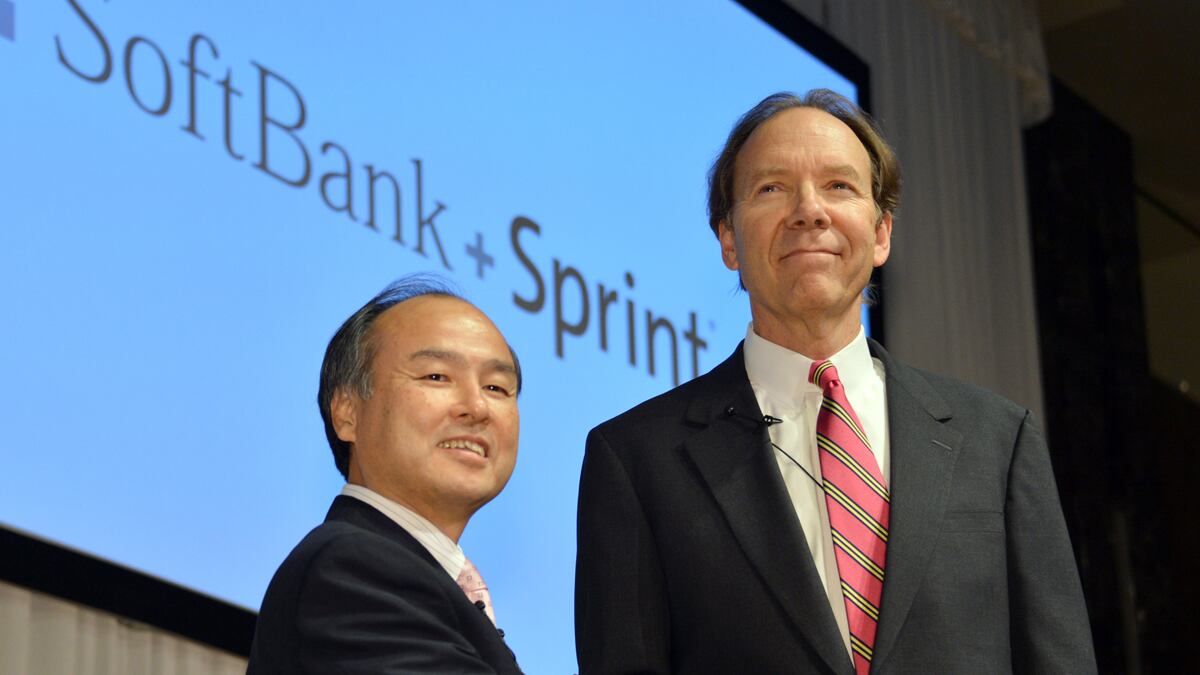

American firms may be looking for growth everywhere but at home. But Masayoshi Son, the billionaire head of Softbank, was eager to gain a foothold in the United States. The U.S. cellphone-and-wireless-communications market may not be growing at a BRIC-like pace, but at least it is growing. That’s more than can be said for Japan’s telecom markets, where, according to Bloomberg, shipments of new phones have fallen 27 percent in the past five years.

The same dynamic that pushed Softbank to rush into Sprint is spurring other companies in slow-growing Japan to seek growth in the U.S. Meanwhile, Japan has emerged as an unlikely and attractive source of cash for a deleveraging America.

Japan has long been derided as the sick man of the industrialized world. But today, Japanese companies and banks are surprisingly healthy and cash rich. While European banks and pension funds gorged themselves on American subprime real estate and Spanish airports, Japan’s banks largely avoided subprime mania. And while they were burned by a stock and housing bubble that disastrously popped in the early 1990s, Japanese banks have finally been restored to an approximation of health. Arthur Alexander, an adjunct professor at Georgetown and a Japan expert, said that “Japanese companies have good healthy banks behind them and lots of money.”

Japanese companies are sitting on a large cash pile—some $2.6 trillion worth. But they’re reluctant to spend the money at home due to Japan’s slowly growing economy and declining population. Japanese corporations have realized that “foreign markets are where the future is,” said Curtis Milhaupt, a Japan specialist at Columbia Law School. The money leaves in Japan in the form of investment in foreign companies, the purchase of assets and financial products, as well as outright takeovers and acquisitions. The McKinsey Global Institute estimates that if current mergers-and-acquisition trends continue, “Japanese cross-border M&A activity will soon surpass its 1990 peak.”

The cumulative total of Japanese foreign direct investment in the United States totaled 289 billion in 2011, up more than 50 percent since 2005. That makes Japan the second largest foreign investor in the U.S. after England. Since 2005 Japanese investment has flowed into the U.S. at a steady pace of between $10 billion to $15 billion a year.

The investment has taken the form of American subsidiaries of Japanese companies expanding their operations (i.e. Honda building a new car factory) as well as Japanese companies buying stakes in American firms. The pharmaceutical company Takeda, whose American subsidiary is based in Deerfield, Ill., has been snapping up American companies for years. Mitsubishi saved Morgan Stanley in 2008 at the height of the financial crisis by buying a $9 billion stake in the investment bank. Just last month, Mitsubishi bought a San Francisco-based aircraft-leasing company for over $1 billion.

But we’ve heard this story before, right? In the 1980s and early 1990s, Japanese companies could raise as much as they ever wanted in the booming Japanese stock market. With interest rates low, Japanese capital—buoyed by a strengthened yen—flooded into the United States in the form of high profile, ill-conceived purchases like Rockefeller Center, Columbia Records, and Pebble Beach. The investments also inspired a sense of fear, loathing, and even paranoia among insecure Americans—as best represented by Michael Crichton’s xenophobic novel Rising Sun.

Today’s Japanese buying spree is also buoyed by a strong yen, which is approaching record levels against the dollar. But it is more restrained than the 1980s-era investment boom. Japanese companies are now concentrating their firepower on productive assets and operating companies, as opposed to flashy real-estate purchases.

Curtis Milhaupt said that Japanese companies have also become much more cautious and savvy as foreign investors. Milhaupt described the structure and price of the Sprint deal as “more strategic and better thought through, the price is not extravagant.” He characterized it as part of a pattern of “more strategic, careful, and sophisticated dealmaking by Japanese firms.”

Japanese companies in the United States have also improved their corporate citizenship, Milhaupt said, and are no longer seen as the job-destroying, imperialistic conglomerates that terrified the American public in the 1980s and early 1990s.

The Sprint announcement has touched off hardly any security or competiveness concerns. By contrast, a recent House Intelligence Committee Report accusing Chinese telecommunications companies Huawei and ZTE of espionage. “China has replaced Japan as the bogeyman of East Asia in terms of international investment,” said Milhaupt.

Today, Japanese companies are more likely to be seen as job creators than potential spies. According to a survey conducted by political scientists Nathan Jensen and Edmund Malesky, 61 percent of respondents said that Japanese investments are good for the U.S. economy, compared to 55 percent for generic foreign investment and only 33 percent for Chinese investment. That Japanese investment could be seen as no better or worse than foreign investment as a whole represents a marked change from American attitudes during the last Japanese investment boom.

Arthur Alexander conducted focus groups in 1994 and 1995, in which the prevailing sentiment seemed to be: “[Japan is] is out to get us, we bombed them and they’re getting us back.” When he redid the focus groups in 2001, the attendees were “aware that Japan was having hard times and can’t get out of recession,” and instead viewed China as the major economic threat.

The face of Japanese investment in the United States has changed with American attitudes towards it. Today, Japanese car companies operate some 56 U.S. auto-manufacturing plants, according to the Organization for International Investment. And they’re perfectly happy to promote the number of jobs they sustain and partner with cities and states who compete for their investment. “[Japanese companies] have adapted and understand that employment is a big part of what any host government is looking for,” Milhaupt said. Japanese companies have become more sensitive to American politics, and so politicians and the public have become more welcoming to their investments. In a press conference in Tokyo announcing the Softbank takeover, Sprint CEO Dan Hesse said: “It could not be a better time to get this investment of capital.”