For 47,745 of the 47,763 runners who competed in the New York Marathon in 2011, it was a co-ed race. Women ran alongside men, and as demanding sports such as endurance running have become socially acceptable for women, females formed an ever greater part of the pack. But for the first 18 racers, the top 0.04 percent, the marathon is exactly as segregated as it was before 1971, when women were banned from racing more than 10 miles on the theory that their delicate bodies weren’t up to the strain.

Becoming a plutocrat is like being one of those 18 men. This is not to suggest that women are somehow biologically precluded from breaking into the plutocracy, in the way that the female physique may never run a marathon as quickly as the male one. But the image is a way of illustrating a significant and rarely remarked-on aspect of the rise of the super-elite: it is almost entirely male. Consider the 2012 Forbes billionaire list. Just 104 of the 1,226 billionaires are women. Subtract the wives, daughters, and widows and you are left with a fraction of that already small number.

What’s especially striking about this absence of women at the top is that it runs so strongly counter to the trend in the rest of society. Within the 99 percent, women are earning more money, getting more educated, and gaining more power. That’s true around the world and across the social spectrum. If you aren’t a plutocrat, you are increasingly likely to have a female boss, live in a household where the main breadwinner is female, and study in a class where the top pupils are girls. As the 99 percent has become steadily pinker, the 1 percent has remained an all-boys club. One way to understand the gap between the 1 percent and the rest is as a division of the world into a vast female-dominated middle class ruled by a male elite at the top.

Another window into how the gender divide sharpens at the very top comes from the Goldin and Katz Harvard study. College is one of the arenas the women of the middle class are conquering—more than half of all U.S. undergraduates are now female, and their grade-point average is higher than that of their male peers. Young women are more likely to get their bachelor's degrees and go on to graduate school. The recession has exacerbated the gender divide, with young women responding to a tough job market by going back to school and improving their skills. Young men have not. At Harvard, which released women from the apartheid of Radcliffe only in 1973, the incoming first-year class in 2004 included more women than men.

But as soon as they graduate, Harvard women’s chances of getting to the very top decline because of the jobs they choose. Goldin and Katz found that finance and management were overwhelmingly the most lucrative fields, with financiers earning that whopping 195 percent premium. Men have responded to this incentive strongly—of the class of 1990, 38 percent of the men worked in management and finance 15 years after graduating, compared to just 23 percent of the women. By 2007, the number of women starting off in finance or management had jumped to 43 percent, but a staggering 58 percent of the men had made that same choice. You can see the difference in their incomes: in 2005, 8 percent of Harvard men earned more than $1 million; just 2 percent of the women crossed that threshold.

Not too many people talk about the absence of women at the very top. That’s partly because, in a fight that’s been going on since the famous debates between Lenin and Bolshevik feminist Alexandra Kollontai, the left has a history of bullying women who dare to talk about gender at the apex of power. Doing so has been framed as a selfish concern of upper-class women, who are urged to focus their attention on the more deserving problems of their sisters at the bottom. As for the right, it has historically preferred to avoid discussion of gender and class altogether.

But the absence of women in the plutocracy is an important part of the culture of the 1 percent and a crucial way the very rich differ from everyone else. It is a powerful force in the workplace, where most plutocrats have no female peers. And it shapes their personal lives as well. The year 2009 was a watershed for the American workplace—it was the first time since data was collected that women outnumbered men on the country’s payrolls. In 2010, about four in 10 working wives were the chief breadwinners for their families.

The plutocracy, by contrast, still lives in the Mad Men era, and family life becomes more patriarchal the richer you get. In 2005, just over a quarter of taxpayers in the top 0.1 percent had a working spouse. For the 1 percent, the figure was higher, at 38 percent, but significantly lower than in the country as a whole. There’s not a lot of mystery to these choices of the wives of the 0.1 percent, as I discovered at a dinner party when I sat next to a private equity investor. He was in his late thirties with no children, and as we chatted I learned that he had met his wife when they were both students at Yale Law School. But when I asked which firm she now worked at, I realized I had committed a faux pas. If your husband is earning $10 million a year, choosing the treadmill of billable hours really is rather bizarre. (It turns out she spends her time investing part of the family portfolio, studying art history, and decorating their Upper East Side town house.)

And it is graduates of Yale Law School and the like who are the housewives of the plutocrats. In 1979, nearly 8 percent of the 1 percent had spouses the IRS described as doing blue-collar or service-sector jobs—government speak for bosses married to their secretaries. That number has been falling ever since. What economists call assortive mating—the tendency to marry someone you resemble—is on the rise. But while the aggressive geeks of the super-elite are marrying their classmates rather than their secretaries, their highly educated wives are unlikely to work.

My own suspicion is that most plutocrats privately believe women don’t make it to the top because something is missing. Most know better than to muse on this matter in public—they all remember, for instance, what that cost Larry Summers, who happens to have a sterling record of promoting the careers of his female protégés—but I can report an unguarded remark one private-equity billionaire made to me. The problem, he said, wasn’t that women weren’t as smart or even as numerate as men; he had hired many women in starting positions who were as skilled as their male counterparts.

But they still didn’t have the royal jelly: “They don’t have the killer instinct, they don’t want to fight, they won’t go for the jugular.” By way of evidence, he described a subordinate who had cried when he told her she had made a mistake. You can’t do that and win, he said.

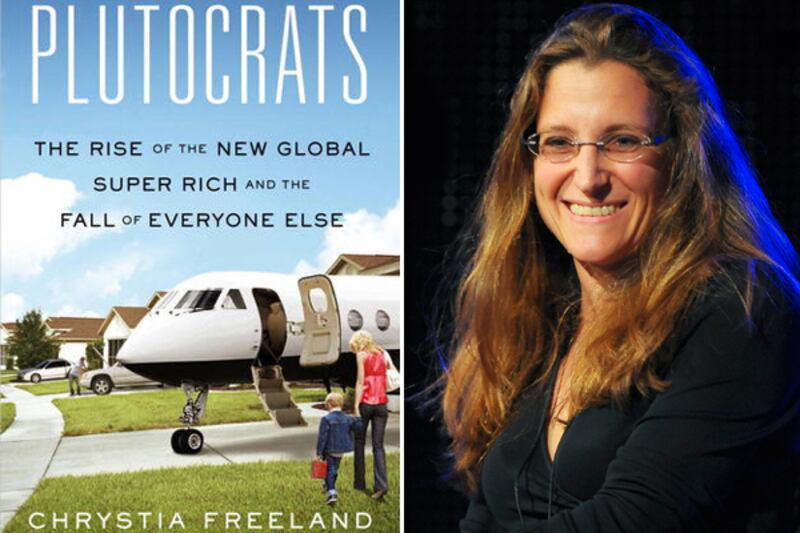

Excerpted from Plutocrats by Chrystia Freeland. Reprinted by arrangement with The Penguin Press, a member of Penguin Group (USA), Inc. Copyright © Chrystia Freeland, 2012.