Tuesday’s headlines gave Mitt Romney a golden opportunity to attack President Obama and his “green” energy agenda during the second presidential debate. A123 Systems, the electric-car-battery maker that got a $249 million grant from the Department of Energy in 2009, filed for bankruptcy in a Delaware court.

The collapse of A123—as well as the January bankruptcy of another electric-car-battery maker, Ener1, the recipient of a $118 million DOE grant—provides yet another example of the Obama administration’s costly and unsuccessful backing of the electric-car business.

The administration has handed out $2.4 billion in grants to the EV sector, as well as nearly $2.6 billion in loans. None of those bets has paid off. Car buyers are staying away from all-electric vehicles in droves. And yet, for some reason, Romney avoided the subject in the debate.

Although the A123 bankruptcy was the most obvious example of Obama’s failed foray into the car business, Romney could have pointed to a number of other reports over the past few weeks to make the same, obvious point: the Obama administration should not be picking winners in the hypercompetitive business of making and selling automobiles.

Perhaps the most damning assessment of EVs came from the Congressional Budget Office in a September report (PDF). The CBO estimated that the lifetime cost of owning an electric vehicle or plug-in hybrid is $16,000 to $19,000 more than that of a conventional car. Despite those higher costs of ownership, the CBO estimated that federal subsidies for EVs will total $7.5B over the next seven years.

That’s a lot of money considering that the combined sales of the most-hyped EVs—the Nissan Leaf and Chevrolet Volt. Over the first nine months of the year, 9,674 Leafs and 7,671 Volts were sold. So at roughly 2,000 EV sales per month or 24,000 per year, and subsidies of about $1 billion per year, each EV sold is costing taxpayers about $41,666. At that rate, taxpayers would be better off if they simply gave each EV buyer 10,000 gallons of gasoline (at $4/gallon) and had that driver continue piloting his old car. Instead of cash for clunkers, we could call the new anti-EV program gas for clunkers.

If those CBO subsidy numbers aren’t depressing enough, consider this lagniappe from the number crunchers: EVs do little or nothing to cut carbon-dioxide emissions. EVs burn less gasoline than other vehicles. But the CBO notes that this efficiency allows carmakers to build and sell even more pickup trucks, SUVs, and other fuel-hogging vehicles while still complying with federal rules on overall fleet efficiency. “Consequently, the tax credits will have little or no impact on the total gasoline use and greenhouse-gas emissions of the nation’s vehicle fleet over the next several years,” said the CBO.

The CBO report roughly coincided with the announcement by Toyota Motor Co., the world’s biggest automaker, that it would effectively quit making all-electric cars and instead focus on the hybrid-electric market. As Toyota vice chairman Takeshi Uchiyamada bluntly explained: “The current capabilities of electric vehicles do not meet society’s needs, whether it may be the distance the cars can run, or the costs, or how it takes a long time to charge.”

Uchiyamada was merely rephrasing the same suite of problems that have plagued the promoters of all-electric cars for more than a century: the vehicles don’t have enough range, take too long to refuel, and cost way too much. That point was reinforced last year in a report issued by Deloitte Consulting (PDF) that found the most likely buyers of electric cars are people with household incomes “in excess of $200,000.”

Earlier this month, researchers at Norway’s University of Science and Technology compared the life-cycle environmental costs of EVs with those of conventional vehicles. Their conclusion: “The global warming potential from electric vehicle production is about twice that of conventional vehicles.” The report differentiates between EVs fueled with low-carbon sources like nuclear or renewable energy, and finds that in Europe, EVs could provide a substantial reduction in greenhouse gases, up to 24 percent. But the researchers also conclude that “EVs exhibit the potential for significant increases in human toxicity, freshwater eco-toxicity, freshwater eutrophication, and metal depletion impacts, largely emanating from the vehicle supply chain.”

While EV promoters may argue the environmental merits of their favored vehicles, they cannot argue the industry’s lousy economics. Those troublesome numbers are the reason why Shai Agassi, founder of an electric-car company called Better Place, is now out of a job. In July 2008, Thomas Friedman of The New York Times dubbed Agassi, a former executive at SAP, “the Jewish Henry Ford,” who was launching “an energy revolution” that would end the world’s “oil addiction.”

Yes, well. On Oct. 1, Agassi was ousted as CEO of Better Place. The company, which is based on the belief that carmakers will agree to build vehicles that accept swappable batteries supplied by Better Place, has raised about $800 million over the past five years. Its losses since 2010: about $477 million, including losses of about $64 million in the second quarter of 2012.

The failure of A123 won’t be the last. Fisker Automotive, which makes a super-luxury hybrid-electric sports car, is delaying its long-awaited sedan, the Atlantic. Tesla Motors, the publicly traded maker of high-dollar EVs, which got a $465 million loan from the DOE, announced recently that it was slashing its production plans for its sedan, the Model S, from 5,000 units to 3,000 for this year. The base price for that four-door machine: $57,400, which is roughly the price of a BMW 535.

That price tag provides yet another opening for Romney: why is the Obama administration backing companies that make EVs that are only affordable to the Beemer and Benz buyers?

And why are the check writers in government still throwing money at the industry? Last week, the California Energy Commission approved a $10 million grant to Tesla, which the company will use on a new factory in California that will make an all-electric SUV.

Last April, I predicted that A123 would be bankrupt within 18 months. It took only six months. Given my call on A123, I’m ready to make another prediction: within two years Tesla Motors will be bankrupt or forced to sell itself to another company.

I’m making my Tesla prediction based on the company’s financials: Tesla lost $195 million over the first six months of the year, and it has been forced to sell more stock in order to stay solvent. In each of the last four quarters, the company’s revenues have fallen and its losses have increased. It appears that the more cars Tesla makes, the more money it loses.

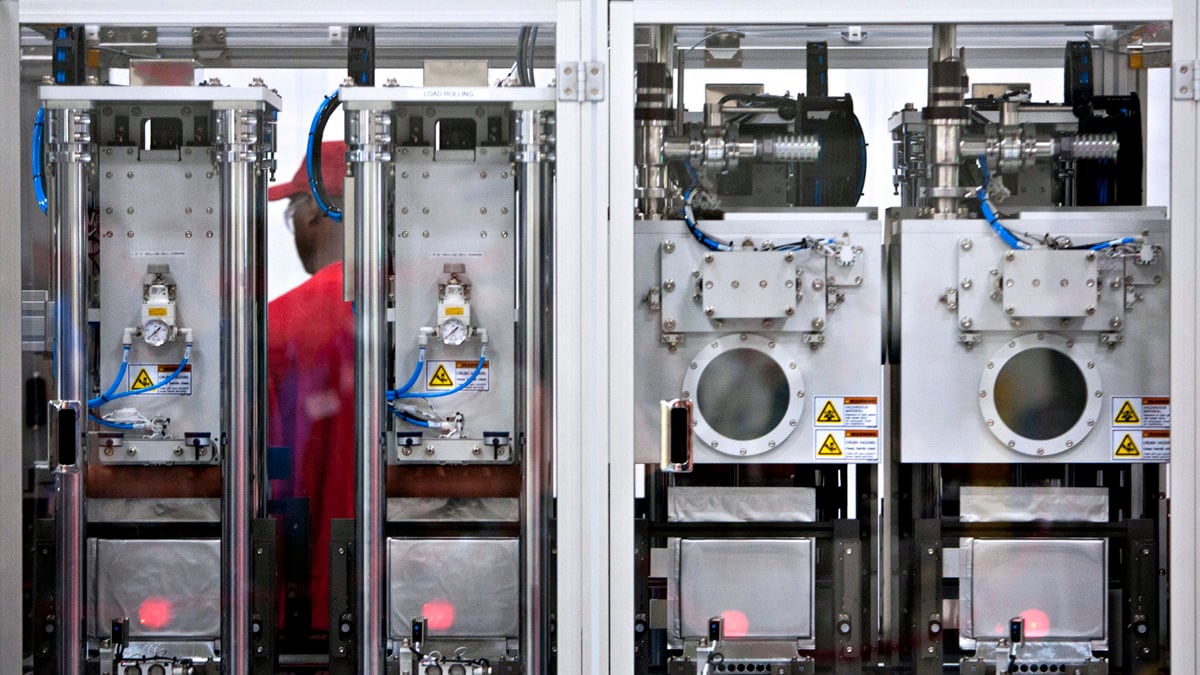

The punch line here is readily apparent: the much-hyped electric-car sector is circling the drain. Two years ago, Obama declared that A123’s new factory in Livonia, Mich., marked “the birth of an entire new industry in America.”

The third and final debate presidential debate is next Monday. If Romney wants to win it, he’d do well to keep that quote—and the bankruptcy of A123—high on his list of talking points.