There’s no denying it: we love our psychopaths. Whether its stoic protagonists or ice-blooded villains, we can’t get enough. Look at the most celebrated film performances in the pop-culture canon and you’ll find no shortage of murderous charmers (see Anthony Hopkins’ Hannibal Lecter and Heath Ledger’s Joker).

Any list of the most widely watched television shows of the last 15 years has to include Law & Order, CSI, and a fairly indistinguishable mess of other crime procedurals, rich in chalk outlines and forensics labs. Auteurish bloodbaths from Quentin Tarantino, Martin Scorsese, and Oliver Stone are always reliable box-office draws. And let’s face it, we’re not buying Stieg Larsson paperbacks by the millions for his effortless prose style.

To be sure, we despise beyond comprehension the real-life psychopaths and the detestable acts they carry out, be they Anders Breivik or Osama bin Laden. But that doesn’t seem to temper our shared cultural predilection for the fictional variety—which seems both insatiable and, the more we think about it, less than healthy. In fact, it’s probably something worth consulting a professional about.

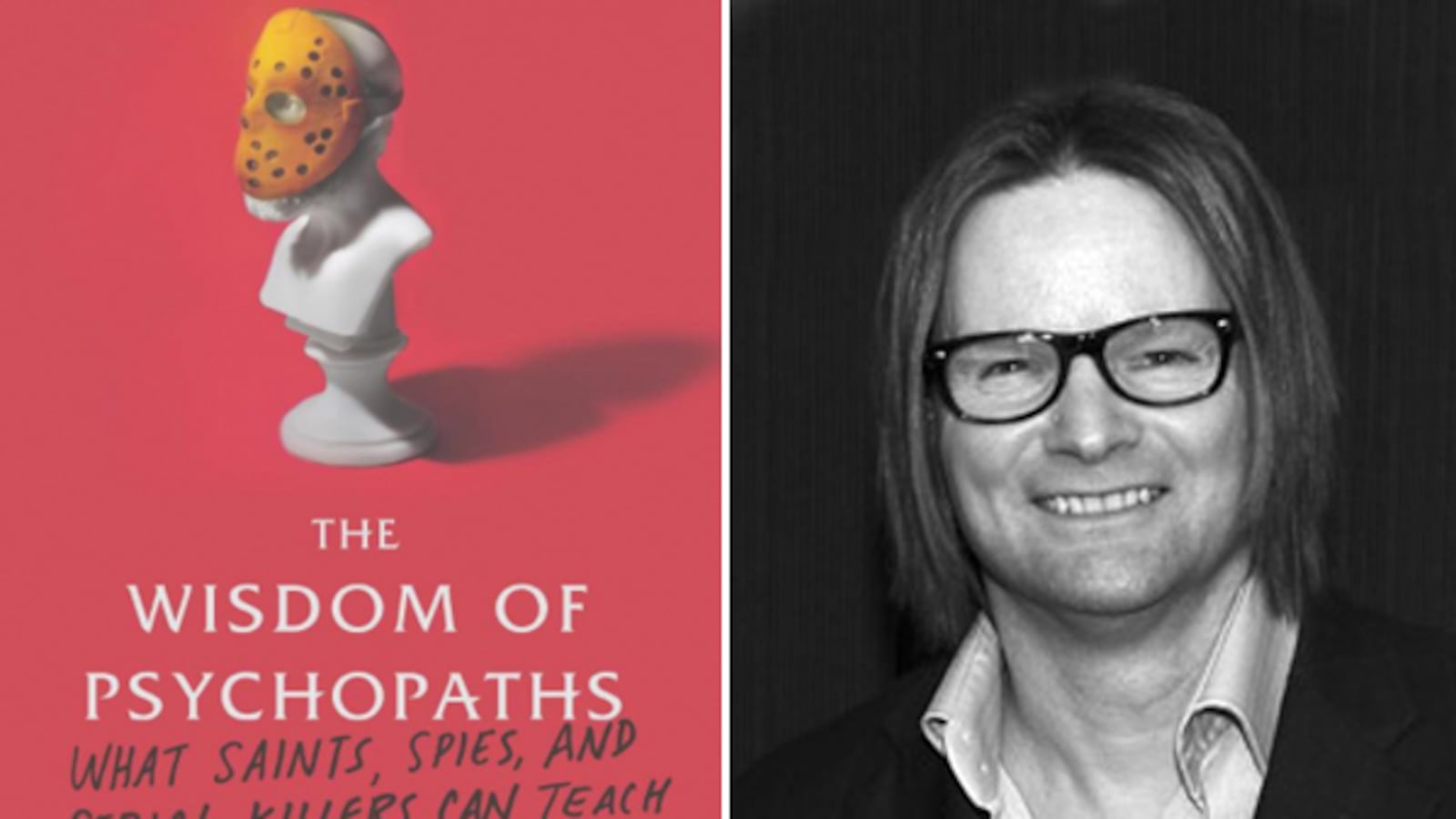

For those who fret about this compulsion, you needn’t go it alone; help is available. In fact, in his entertaining new book The Wisdom of Psychopaths, University of Cambridge research psychologist Kevin Dutton sheds some light on the stunning magnetism of the ethically challenged.

The book delves into the science of psychopathy with the hope of uncovering how we can all improve our lives by unlocking our inner Ted Bundy (you too can be a psychopath!). And while such a “Chicken Soup for the Soulless” literary aim might seem macabre, first consider that the trademarks of this condition—coolness under pressure, determination in the face of adversity, bulletproof self-confidence, and easy social charm, to name a few—are all characteristics that we strive to acquire, at least to some degree.

Just think, when we saunter into the boss’s office to ask for a raise or try to win over an incredulous potential client, we all wish we had a little more James Bond steeliness to summon.

Without a doubt, psychopaths are frightening characters. Some of their other typical features include a resistance to self-blame, an enhanced capacity for dishonesty, a disregard for the feelings of others, and a complete lack of remorse—all of which, unsurprisingly, helps give rise to wrongdoing of the highest order. As Dutton notes, “[a]round 50 percent of the most serious crimes on record—crimes such as murder and serial rape, for instance—are committed by psychopaths, and continue to be committed by psychopaths.”

But it’s just as important to understand that psychopathy isn’t as all-or-nothing as we sometimes think. “Just as there’s an official dividing line between someone who plays recreational golf on the weekends and, say, Tiger Woods,” Dutton writes, “so the boundary between a world-class, ‘hole-in-one’ superpsychopath and one who merely ‘psychopathizes’ is similarly blurred.”

Once you realize this, things get pretty interesting. In fact, one of the most jarring realizations that Dutton comes to is that functional psychopaths walk among us. Consider the steady-handed neurosurgeon with the outsized ego, the larger-than-life CEO, and, yes, the Teflon-coated politician. One can almost envision a dark party game that involves ranking our favorite historical figures on a scale of psychopathy.

In fact, Dutton mentions a study by psychologist Scott Lilienfield, who looked at the results of a survey that queried presidential biographers about the personality traits of former White House occupants. As Dutton explains, “the results made interesting reading. A number of U.S. presidents exhibited distinct psychopathic traits, with John F. Kennedy and Bill Clinton leading the charge.” Surprised?

Indeed, those at the higher end of the psychopathic spectrum are often stars in the professional world. Put another way, they are what every doting parent wants their precocious toddler to grow up to become. (Seriously, what the hell is wrong with us?)

According to the Great British Psychopath Survey, a project launched by Dutton, CEO, lawyer, media professional, and salesperson top the list of most-psychopathic occupations in the U.K. Other notable psychopath-heavy professions include chef, civil servant, and—you’ve got to love this—clergyperson. It’s hard to imagine that a similar study of American professions would yield very different results.

But it goes even further than that. Turns out everyone from Saint Paul to Zen Buddhist masters are identified by Dutton as possible psychopaths too. “[T]here’s evidence to suggest,” he writes, “that, deep within the corridors of the brain, psychopathy and sainthood share secret neural office space.” In fact in many environments, psychopaths can prove more altruistic than the rest of us.

Therein lies the tension that drives Dutton’s book, and might actually help explain our strange attraction to such rebels without causes. It’s also why a grown-up treatment of this incredible set of mental qualities makes for such absorbing reading.

The science behind all of this is fairly intuitive. Psychopathic traits have been given the Darwinian OK throughout the history of human evolution, which helps validate Dutton’s argument that these qualities can be pretty important tools if properly used. The “seven deadly wins” of psychopathy that he identifies (ruthlessness, charm, focus, mental toughness, fearlessness, mindfulness, and action) are all arrows we want in our quiver. And come to think of it, they also happen to be the very character traits that engage and—dare I say—inspire us when we find ourselves shamelessly hooked on whatever cadaver-filled cable drama is animating our vicarious lives this week.

But Dutton’s assertion that we can learn from psychopaths might be a bit of stretch. It’s a provocative thesis, to be sure. But by pushing this line a bit too hard, he sometimes falls victim to the pervasive habit among popular psychology writers to turn every insight into a self-help strategy. Fortunately, that doesn’t make his treatment of the subject any less interesting.

As Dutton puts it: “The problem with psychopaths isn’t that they’re chock-full of evil. Ironically, it’s precisely the opposite: they have too much of a good thing.”

Which should offer minor consolation the next time we wrestle with our divided hearts, simultaneously adoring and abhorring some artful piece of onscreen depravity.