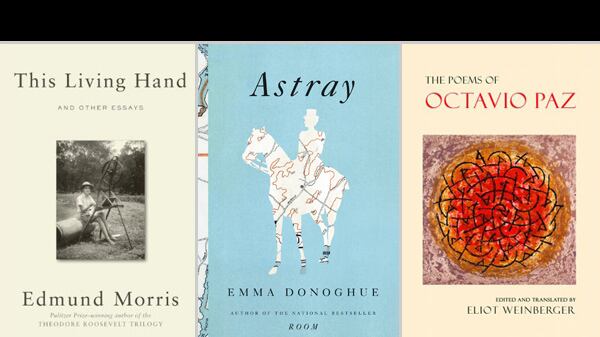

Astray by Emma Donoghue

The author of ‘Room’ displays her mastery at inventing the speech of the most unlikely characters in this story collection.

How do people sound? That’s one of the primary concerns of a writer. Get that right, and everything follows. Donoghue gets it right, as anyone who’s read Room would know. In that remarkable, terrifying novel whose very mention sends my heart rate up and up, she reproduces the speech of Jack, a 5-year-old boy who lives in a tiny room with his mother with no contact with the outside world. Here he is seeing his first sunset: “I watch God’s face falling slow slow even orangier and the clouds are all colors, then after there’s streaks and dark coming so bit-at-a-time I don’t see it till it’s done.” That “slow slow,” “orangier,” using dark as a noun and the exhilarating “bit-at-a-time”—what perfect control she wields. Reproduce is inaccurate, for she does the opposite. She invents, creates, stylizes. You’ve probably never met a 5-year-old boy who’s only ever lived in a tiny room with his mother, but reading Room, you are positive he would sound like Jack. It takes bucketsful of imagination to pull it off, and you wonder whether Room is a one-off. Then you read the short stories in Astray, and you realize this is how she writes! I’ve got plenty more where that came from, she might be saying. Almost all of her characters in this new collection are based on real people, and she writes briefly about their origins after every story. In “Man and Boy,” she introduces Matthew Scott, a zookeeper in P.T. Barnum’s circus, who talks to Jumbo, his African elephant. “Anyway, the superintendent has an iddy-fix that you’re a danger to the kiddies, now you’re a man, as it were. Oh, you know and I know that’s all my eye, you dote on the smalls.” Again, it’s the things that sound “wrong” that transfixes you, the “iddy-fix,” a few words seems to be missing between “kiddies” and “now you’re a man,” the “as it were,” (as it were what?) whatever “that’s all my eye” means. In “Onward,” she was piqued by Caroline Maynard, a woman who called herself Mrs. Thompson, was forced into prostitution and who stirred Charles Dickens’s imagination for 18 months when her brother Fred wrote to the great writer and philanthropist asking for help. But without knowing any of that at the start of the story, it is extraordinary to read lines like these: “‘We saved you the last of the kippers,’ she says in a tone airy enough to give the impression that she and Pet had their fill of kippers before he came down this morning. Mouth full, Fred sings to his niece in his surprising bass.” Is there a tone airy enough to give such an impression? And why is it surprising that Fred is a bass? One has to read Donoghue a few times to fill in the blanks, and there are many blanks; is “Pet” perhaps a typo for “Peter”? Donoghue reads like she takes a dry eraser and deletes chunks of letters and words—there’s something constantly missing, and parts of the world are a mystery. But isn’t that how we think to ourselves, as Joyce demonstrated, skipping over the river of thoughts and refusing to bother explaining the obvious or the visual? With such ingenuity, Donoghue achieves the effect of creating magic and wonder in the real world. To follow Donoghue into the unknown is one of the most pleasurable experiences I can think of.

This Living Hand by Edmund Morris

The fresh and nimble essays of the biographer of heavyweights such as Roosevelt, Reagan, Beethoven, and Edison.

You might think of him as Edmund Rex, the legendary biographer who has since merged with his subjects. His first of a three-part trilogy, The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt (then came Theodore Rex and Colonel Roosevelt), was so spectacular that it not only won the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award, but the president of the United States at the time asked Morris to be his official biographer. The resulting experimental narrative, Dutch: A Memoir of Ronald Reagan, caused an uproar. Morris wrote as if the “fictional” “Arthur Edmund Morris” had been tailing the charismatic superstar Ronald Reagan all his life, a sort of Brian following Jesus, Boswell chronicling Johnson. It conveyed as no conventional biography can that Reagan was a born thespian “with extraordinary grace,” “one of the strangest men who’s ever lived,” not so much human as a character out of a Greek drama. But those who were shocked by the literary device must not have followed Morris’s career, for This Living Hand’s essays make clear that this is a man who never snaked through a narrative the same way twice. He writes with originality and surprise every time, whether about presidents (not just Roosevelt and Reagan, but also Jefferson, Madison, Clinton, Obama), Nadine Gordimer, his wife, classical music (he is a man possessed by Beethoven), or the art of biography. He knows every trick and conspires to use them all—he is a billionaire who spends every cent. And just as any self-respecting billionaire knows, the sweetest thing you’ll ever taste is that first beer you bought with that first paycheck. Likewise, it is the collection’s first entry and earliest piece, “The Bumstitch,” a lament for the rarest of fruits, from 1972, that is, to me, the best. It is effortless, hasty, tasty, autobiographical, strange, surprising, twisting, graceful, rich, beautiful, haunting, and devastating. He was 32, and his happy future lay ahead of him.

American Phoenix by Sarah S. Kilborne

The story of a penniless immigrant who built a silk empire, lost it in a flood, and somehow regained it all.

At 7 o’clock on May 16, 1874, a Saturday morning, the poorly designed and built reservoir dam on the Mill River in western Massachusetts suddenly burst, sending millions of tons of water down a valley full of factories and farms. It was one of the first major dam disasters in U.S. history and one of the biggest catastrophes in the 19th century; 139 people were killed, and 740 were made homeless. It wiped out the village of Skinnerville with its mills famous for producing the country’s best silk. The town was named after William Skinner, who came to the U.S. from London without a penny and created a silk empire worth millions. But within an hour most of what he built was swept away. Kilborne, who is the great-great-granddaughter of Skinner, perhaps makes a tad too much of a mythic hero out of her great-great-grandfather, as if he had to bounce back from life, again! After all, he wasn’t exactly penniless a second time, and it wasn’t like no one would give him a line of credit. Canonizing Skinner as an “American phoenix” is not a completely convincing take on his story, but rather like squeezing him into a thin and silky gown; of course it’ll tear. But through those holes one can peep into the past, when America was growing, contractors were greedy, engineers were careless, county commissioners were dishonest, and lawmakers were corrupt. Those traits characterize China today. Indeed, America is a phoenix—it took disasters to force her to learn how to expose negligent practices, protect her public, and ensure the safety of her workers and families with stronger laws. Tomorrow’s superpower seems to have learned from our example to rise from the ashes of its masses.

The Poems of Octavio Paz Edited and translated by Eliot Weinberger

At last, a selection of the Nobel laureate’s poems spanning his entire 65-year career.

Paz was born in Mexico City in 1914 and died in the same city in 1998. For most of those years he wrote continuously and also became his country’s ambassador to India. He became his country’s literary ambassador in 1990, when he won the Nobel Prize in Literature. Reading this volume, which is the first to survey the very prolific poet’s career from beginning to end, one wonders if he has aged poorly, or whether the imagery that he found so enchanting are too commonplace today to be awestruck by, or perhaps the music of his language is lost in the translation? The last of these concerns can probably be waved off by noting that the editor and principal translator Eliot Weinberger is without peer in his long and loyal appreciation of Paz for more than four decades, and that additional translations are by such greats as Elizabeth Bishop, Paul Blackburn, Denise Levertov, Muriel Rukeyser, and Charles Tomlinson. Yet, Paz’s poetry fails to surprise and unsettle. One might not expect the first selection, “Game,” from 1931, to already possess genius, but the manifesto-like pronouncement of “I’ll plunder seasons./I’ll play with months and years./Winter days with the red faces of summer” sounds rather like the frustrations of a Red Sox fan. But the last one in the book, “Response and Reconciliation,” from 1996, has the same uninspired New Age reductionism: “Man and the galaxy return to silence./Does it matter? Yes—but it doesn’t matter:/we know that silence is music and that/we are a chord in this concert.” You’d have to sit through perhaps his most famous poem, the long “Sunstone” from 1957, to witness lines that don’t sanctify or propound, lines like “tigers drink their dreams in those eyes” and “your breasts two churches where blood/performs its parallel rites.” Those moments, alas, are few, and Paz’s surrealism presents pictures of dreams and of the Orient that most Americans have since seen for themselves. Perhaps Paz demonstrates how improbably difficult it is for even very good poetry to feel immortal—how the strangeness of Milton, Whitman, or Neruda is a most heroic rallying of everything against the tyranny of time.

Care of Wooden Floorsby Will Wiles

A farce that doubles as a primer on how not to house-sit for an irritating friend who goes on and on about his ridiculous expensive wooden floors.

Wiles used to be the deputy editor of the British architecture and design magazine Icon, so of course his first novel is about a man who house-sits an immaculate flat owned by his college dormmate Oskar, who might or might not be getting divorced by his wife. In this comedy, Oskar, the composer of Variations on Tram Timetables, is designed to be a caricature, as if all Eastern Europeans are obsessive-compulsive clean and control freaks who are far too anal and cultured, and leaves written notes like: “Please do NOT play with the piano.” “First, let me address the issue of my friends the cats.” “PLEASE, YOU MUST TAKE CARE OF THE WOODEN FLOORS.” In other words, be 100 percent certain that something will happen to the piano, the cats, and, God forbid, THE WOODEN FLOORS. A few drops of wine spills, and next thing you know, someone is dead. The nightmare ends with a long phone call from Oskar, who apparently is the best body double for God that Wiles can book on short notice. The narrator represents us, the freedom-loving people, who recognize that wooden floors are to be walked on, yet have no choice but to be submitted to a meaningless “test.” I’m not certain whether Wiles wanted to restage and reimagine the epic existential struggle, but whatever the intent, he has rendered Sartre’s philosophy into a trite and pointless farce. C’est la vie.