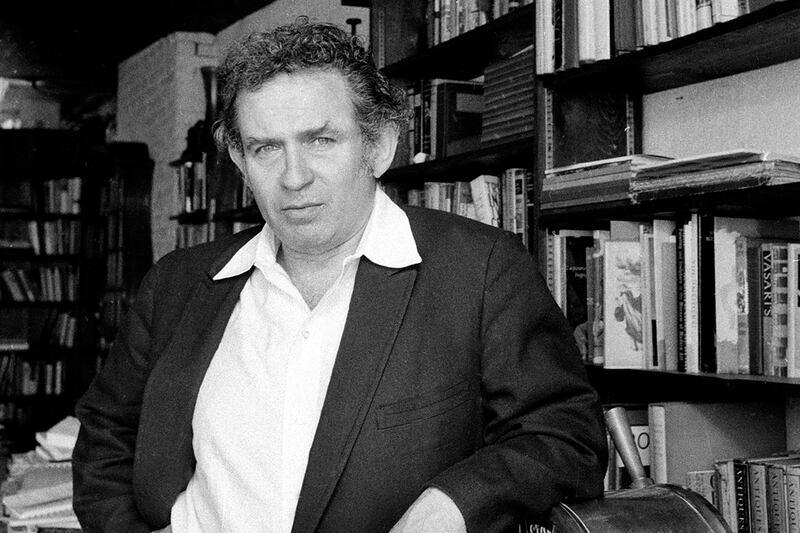

Remarks upon being awarded the Norman Mailer Prize for Lifetime Achievement in Fiction, October 4, 2012

When I’d read the obituary announcing Norman Mailer’s death, I felt such loss, and a sinking sensation—the realization that something had gone out of American literature that wasn’t likely to return. Because Norman represented not only the most passionate and ambitious writing of his generation but the spirit of a kind of American writer who will possibly not come again. Norman was the very antithesis of minimalism—he was a maximalist.

I became acquainted with Norman Mailer in the last 10 or 15 years of his life, at a time when he was, shall we say, mellower than he’d been. By this time he’d been married six times and was at this point married to Norris Church—as you all know Norris was one of the most beautiful women … And her physical beauty was matched by an inner, spiritual beauty—she was really quite extraordinary.

I knew them, if not well, as a couple. The first time I’d met Norman was at an event at Lincoln Center—I think it was a fundraiser for a literacy organization. Norman was the MC. And I was one of a number of writers who were giving readings. When I came out on stage, Norman was gracious and shook my hand and introduced me by saying, “Joyce Carol Oates has written this remarkable book On Boxing.” He let that sink in to the audience, then added, “It’s so good I’d almost thought that I had written it myself.” And there were waves of good-natured laughter from the audience and Norman seemed just slightly puzzled, like—Why is that funny?

Norman had meant his remark as the highest praise. In speaking of Norman Mailer we’re speaking of the male ego raised to the very highest, without which we wouldn’t have civilization, I’m sure.

I have a second Norman Mailer story which made an enormous impression on me when I was a younger writer. Mailer had had an extraordinary success, as you all know, with his first novel The Naked and the Dead, which was published in 1948. Like his distinguished predecessor Lord Byron, he woke up and discovered that he was famous … When you achieve such fame at a young age, your life is irrevocably changed.

So it was. Norman became famous at 26—but he didn’t understand that fame brings with it infamy—in his case, The Naked and the Dead was considered pornography in some quarters. It rose to the top of bestseller lists in the United States and in the U.K. and remained there for 62 weeks.

Then Norman said—(I’m not sure if I am quoting him accurately—Norman had a way of speaking about himself in the third person, which women don’t do; you know there’s something strange when you hear someone speaking of himself as he—so I probably can’t precisely mimic this)—but Norman said of the experience, “Part of Mailer thought he was the greatest writer since Tolstoy, but another part of him thought that he was an imposter—he didn’t know how to write at all.”

Several years later, in 1951, Norman published his second novel Barbary Shore. I hardly need to tell this audience that the critics and reviewers who’d loved Norman Mailer the first time were now all waiting to pounce on him, and the reviews were almost universally negative. (Almost as bad as the reviews that Moby Dick received, which were abysmally negative.)

So it was, Norman Mailer had gone from being acclaimed a genius and heralded as a major new writer to being someone who “couldn’t write at all.” The reviews were deeply insulting. So, as Norman said—(again, I’m not quoting him precisely)—“he felt like a punch-drunk boxer who’s been hit by his opponent and knocked down and he gets up and gets hit again and he falls down and he gets up and he’s knocked down, and finally the bell rings. And he’s exhilarated and giddy because, though he has been humiliated, he got through the fight.” As Norman said, “Something shifted inside him”—he felt that from now on he would be an outlaw.

I thought that was beautifully expressed: from that point onward, Norman Mailer wouldn’t try to please any audience, critics, or reviewers, he would write the books he wanted to write.

As Oliver Stone said, also so beautifully, this evening—“Writing is a rebellious act and artists are rebels.” There is something transgressive about being a (serious) writer. There is a spiritual component to serious art but there is also a warrior ethic—you must go places where you are not welcome. And critics, reviewers, and others will say, “No one has done this before, or they haven’t done it quite the way you are doing it—therefore, it has to be wrong.”

So a writer must have a certain resilience. And that’s where Norman’s enormous ego came into play and was very valuable. But at the same time, Norman possessed ardor and passion—he had a spiritual, one might say a visionary, commitment to his work. I like to feel that I am like Norman in this. I feel that in my own writing I am trying to bear witness for people who can’t speak for themselves, for one or another reason—they don’t possess the “literary” language, they are not educated, they are disenfranchised politically—they may not even be alive—they’ve had experiences that have rendered them mute.

It’s up to the writer and the artist to give voice to these people. There are two impulses in art: one is rebellious and transgressive—you explore regions in which you are not wanted, and you will be punished for that. But the other is a way of sympathy—evoking sympathy for people who may be different from us—whom we don’t know. Art is a way of breaking down the barriers between people—these two seemingly antithetical impulses toward rebellion and toward sympathy come together in art. So—thank you very much for the honor of this award.