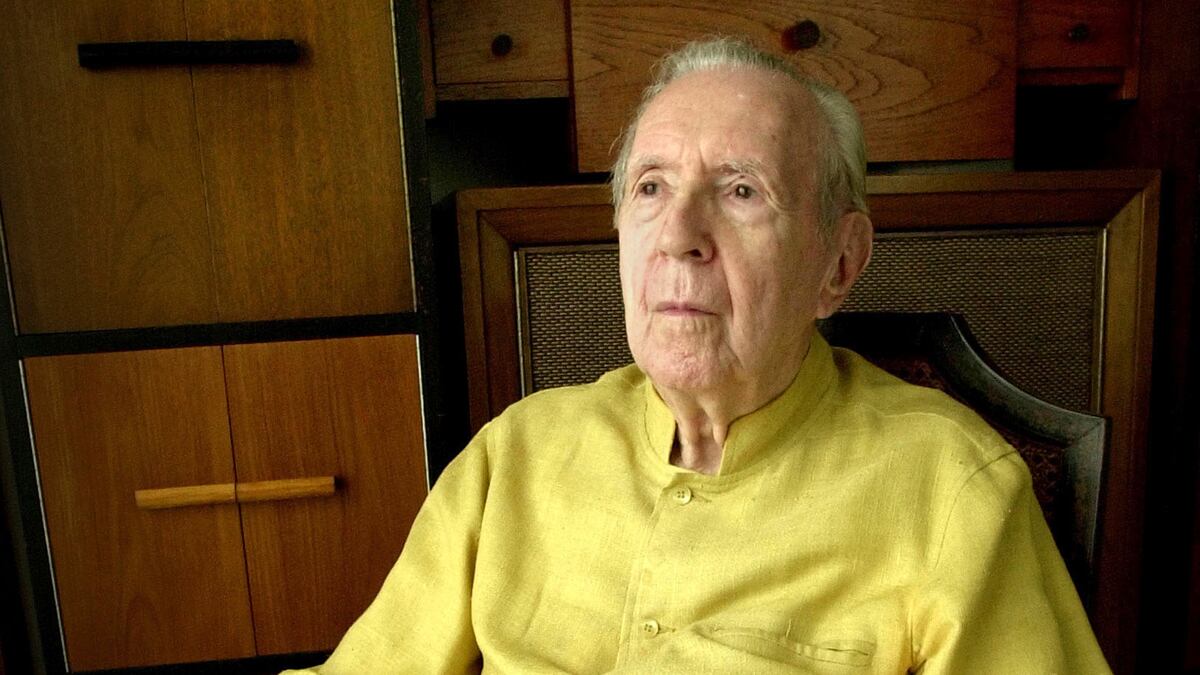

Jacques Barzun, one of the brightest intellectual lights of the twentieth century died last week at the age of 104. Tributes to Barzun, who authored a massive shelf full of books from 1932-2004, will and have been manifold. From Race: A Study in Modern Superstition (1937) to the bestselling tome From Dawn to Decadence: 500 Years of Western Cultural Life (2000), Barzun held aloft the lamp of knowledge. Aside from being an astute culture critic and a wide-ranging intellectual historian and man of letters, he taught at Columbia University from 1928-1975 and wrote extensively on teaching and higher education. The 2007 profile of him in the New Yorker says more than I ever could. I never met him and only know him through his writings, yet I think it’s safe to say that at this time of his departure, he’d want us to also remember his dear friend and intellectual comrade Robert Henry Pitney, who was also born in 1907, but died in 1944, when he and Barzun were both 37. Since Barzun was blessed with an extraordinarily long life, it seems fitting that we remember his friend who had a short one.

In the autumn 1944 issue of the journal Chimera: A Literary Quarterly, Barzun published “In Memoriam: R.H.P., 1907-1944.” Published from 1942-1947, Chimera was a meteor that blazed across the literary landscape and attracted many of the finest writers of its day. The first issue had contributions from Randall Jarrell, Mark Van Doren, Kenneth Burke, Allen Tate, William Arrowsmith, and others. The journal was a direct response to the pressures of World War II: “It is an ominous sign,” one of the founding editors, Fearon Brown, wrote, “that several of America’s most distinguished quarterlies should be forced to suspend activities for the duration. It would seem that the very standards and values we are fighting to preserve are being sacrificed in the effort.” Brown took an excerpt from Franklin Roosevelt’s uplifting and encouraging “A Message to the Booksellers of America” (May 6, 1942) as the epigraph to his journal’s statement of purpose. After the war, Chimera was edited by poet Barbara Howes and Ximena de Angulo. It had depth and breadth. The ever-eclectic Barzun contributed to its special issues on myth and detective fiction. Chimera is completely forgotten now, but it is in its context of its high-mindedness that Barzun memorialized poet, musician, and Renaissance man Robert Pitney, prefacing a selection of Pitney’s fine, quiet, modernist poetry.

According to The New York Times of June 3, 1944, Pitney died “suddenly, in New York City.” Barzun wrote that “if any man lived with art and for it, yet free from all precocity or pride, it was Robert Pitney.

Known to a wide acquaintance as an epicure and a host, Pitney made a still deeper mark on a smaller circle of friends with whom he played music, discussed poetry or the ballet, argued architecture, visited galleries, or matched puns while puzzling out with inexhaustible imagination and knowledge the cryptograms in Finnegans Wake … In his presence the complacent connoisseur might well feel transcended at all points, for Pitney had read, seen, heard, and reflected on all that attracted the attention of alert and catholic minds.

But unlike many even among these things, he did not use art as a refuge from strong feelings or from the chaos of contemporary life. The riches of modern art gave him back in a variety of ordered ways the data of the twentieth century, to which he pretended no indifference. What he was indifferent to was the shifting wind of accepted or fashionable opinion, for the objects that opinion plays upon he knew virtually as a craftsman.”

Much of this could apply to Barzun himself, which is why it’s necessary at this time to remember Pitney’s loss and what it must have meant to Barzun. Pitney was a scion of privilege (as was Barzun) and was among the last of a certain aristocrat-amateur-gentleman-of-the-arts, but he clearly earned his stripes as poet (he published privately) and musician. The Pitneys were an old New Jersey family (that’s a phrase you don’t hear too often) that had inhabited the Garden State since 1722. The photographer Ruth Bernhard (who also lived to be more than 100) recalled working on the famous Pitney farm in Mendham, New Jersey.

She noted in her memoir Ruth Bernhard: Between Art and Life (2000) that Robert and his mother lived together; at the New Jersey estate in the summer and at 1035 Park Avenue in the winter. It is at 1035 Park that I imagine Barzun noticed “after midnight, [Pitney’s] guests having retired, he might be found reading the score of a Mahler Symphony and ready to discuss with you the excellence of its orchestration or the feebleness of its rhythm...” But Pitney, though he “contributed critical notes to Hound and Horn,” was content to remain in the shadows of the culture industry. “An invincible modesty—not shyness—held him back,” wrote Barzun. If there was ever something good to be held back by, that’s gotta be it.

Barzun sums up his memorial by attempting a list of his friend’s qualities, “… the collector of books and prints and music; the generous host and gay conversationalist; the handsome massive figure topped by the great head, once painted by Tchelitchew, but better likened (by Pitney’s own mother) to the most ancient and civilized of the Pharaohs—the full reality of Robert Pitney only an unflagging imagination equal to his could recollect and hold captive in sober memory.” Indeed, the same could be said of Barzun himself. Barzun attempted to carry and celebrate the world that he and Pitney inhabited into a world almost completely transformed, but thanks to the memory that they leave behind, a trace of that world remains.