If you’re like most people, you’ve wondered where you’ll go when you die. The physician Sir Thomas Browne described the two basic possibilities back in 1658: “Some bones make best skeletons, some bodies quick and speediest ashes.” If you don’t know whether inhumation or cremation is right for you, ask your doctor—or ponder Dr. Browne’s pros and cons. “To be knav’d out of our graves,” he wrote, “to have our sculs made drinking-bowls, and our bones turned into Pipes, to delight and sport our Enemies, are Tragicall abominations escaped in burning Burials.” If you’re short on enemies and long on looks, however, keep in mind that “[t]eeth, bones, and hair, give the most lasting defiance to corruption.”

Browne offered these hints in Hydriotaphia, Urne-Buriall, or, A Discourse of the Sepulchrall Urnes lately found in Norfolk, popularly known as Urn Burial. “Popularly” is a ludicrous way to put it. If one knows Urn Burial today at all, it is likely for the macabre hint of prophecy in its Epistle Dedicatory: “But who knows the fate of his bones, or how often he is to be buried?” Browne’s skull wasn’t turned into a haunted-house goblet, but it was indeed dug up, moved, and reburied. Stolen by a sexton from St. Peter Mancroft Church in Norwich, in 1840, it was sold to a surgeon and didn’t make it back into hallowed ground until the 20th century. Now safely interred, the vacant seat of Browne’s intellect can only be studied in a haunting photograph.

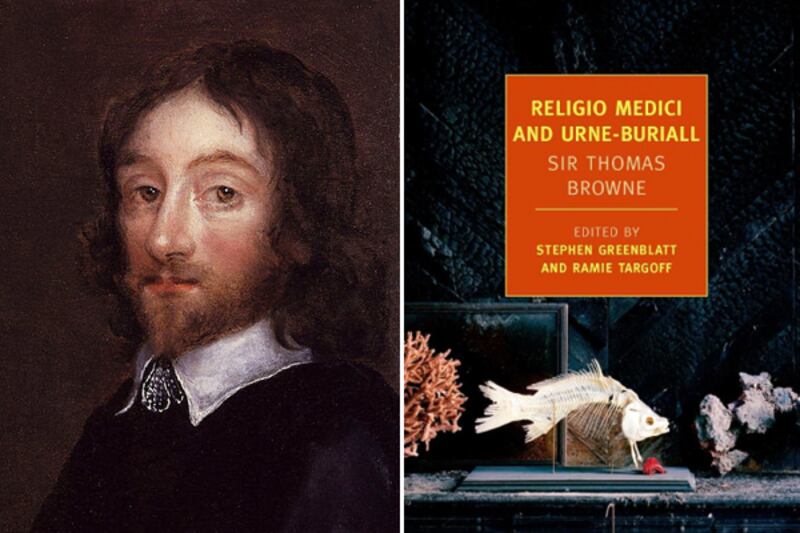

Thanks to a joint effort of NYRB Books, Stephen Greenblatt, author of Will in the World and The Swerve, and Ramie Targoff, a Brandeis scholar and Greenblatt’s wife, Urn Burial has been returned to the public’s indifference in a handsome new edition. NYRB pairs Urn Burial with Browne’s best-known work, Religio Medici, although Urn Burial already had a companion volume in The Garden of Cyrus, or, the Quincunciall, Lozenge, or Net-work Plantations of the Ancients, Artificially, Naturally, Mystically Considered. With Sundry Observations. Frank Livingstone Huntley and Peter Green have explained in great detail why Browne published Urn Burial with The Garden of Cyrus, but Greenblatt mentions Cyrus only in a perfunctory endnote.

That is not Greenblatt’s lone sin against symmetry. In his introduction he asserts that “Browne was born in October 1605” and “died on October 19, 1682, just one month shy of his seventy-seventh birthday.” A careful reader will note that these statements can’t both be true. A fan of Browne will wonder how Greenblatt missed the spooky tidbit that Browne was born on the same date as his death, Oct. 19, lending an eerie quality—Huntley called it “premonitory wonder”—to Browne’s words in A Letter to a Friend:

Nothing is more common with Infants that to dye on the day of their Nativity, to behold the worldly Hours and but the Fractions thereof; and even to perish before their Nativity in the hidden World of the Womb. … But in Persons who out-live many Years, and when there are no less than three hundred and sixty-five days to determine their Lives in every Year; that the first day should make the last, that the Tail of the Snake should return into its Mouth precisely at that time, and they should wind up upon the day of their Nativity, is indeed a remarkable Coincidence.

Browne “wound up” 330 years ago, and the passing of centuries has done little to increase his fame. It is easy to see why NYRB would focus attention on Browne’s most accessible works. The Garden of Cyrus, with its arcane explorations of botany and geometry, may as well be an alchemical treatise or a grimoire. Huntley, who argued that Urn Burial and Cyrus embody opposites—decay and efflorescence, death and life, mortality and eternity—nonetheless acknowledged the former’s unique ability to stand on its own: “Of Browne’s twin essays, readers will continue to prefer Urn Burial, as they do Dante’s Inferno to the Paradiso.” Green, however, said: “They can no more be separated than the voices of a fugue.”

With all due respect to Green, that’s a stretch: Urn Burial can be read, enjoyed, and profited from in wholesale ignorance not only of The Garden of Cyrus but also of Browne himself—his biography, his historical and religious context. The average person will, at some point in his education, encounter Shelley’s “Ozymandias” and believe he’s grappled sufficiently with the vanity of human wishes. Yet Browne’s exhaustive, hilariously resigned treatment of the fate of various bones is the ultimate memento mori. To read it is to accustom oneself to the soil in which he’ll spend eternity.

The “peg” for Urn Burial, to borrow a term from journalism, is the discovery of a cache of Saxon (Browne misidentifies them as Roman) urns containing burnt remains. The various “Solemnities, Ceremonies, [and] Rites of . . . Cremation or enterrment” practiced down through the ages form much of Urn Burial’s subject matter. Browne considers the burial practices of Indians, Chaldeans, Parsees, ancient Germans, Egyptians (practitioners of “a custome . . . [of] deeply slashing the muscles, and taking out the brains and entrails”), Scythians, Chinese, Christians, Muslims, Jews, Greeks, and Romans, in no particular order. “Man is a Noble Animal,” Browne wrote, “splendid in ashes, and pompous in the grave.” The variety of Browne’s anthropological record only emphasizes the common fate of every corpse in history.

Urn Burial is full of quotations fit for long and moody contemplation. “[O]ld Families last not three Oaks,” Browne warned. And: “It is the heaviest stone that melancholy can throw at a man, to tell him he is at the end of his nature; or that there is no further state to come.” The state to come is suggested by the puzzling text of Cyrus, but it is Urn Burial which, in the words of Ralph Waldo Emerson, “smells in every word of the sepulchre.” Browne’s language, which sounds archaic even as it addresses itself to centuries of predecessors, can be a strange comfort. Death is old, it says—and death is old hat. This seems like a physician’s attitude, and Browne does indeed have a wonderful bedside manner.

Urn Burial is a bedside book, a nightstand book, one that begs to be read in a wind-lashed, lightning-struck manor. It reeks of the sepulchre. It seems printed in mildew upon cobwebs, an illustration of the helpless sleep of human reason: “A Dialogue between two Infants in the womb concerning the state of this world, might handsomely illustrate our ignorance of the next, whereof methinks we yet discourse in Platoes denne, and are but Embryon philosophers.” Browne wrote hauntingly of the resemblance between the urn and the womb. He understood death as inevitable, yet couldn’t help speculating about the rebirth it might promise. A physician unto death, his urn was really—what else?—a test tube.