You recently blogged about whether you would ever write fiction. You said that you can’t bring yourself to put your own characters through “torment and travail.” Is it easier if you are simply telling a story that already happened?

It’s easier, in the sense that the bad things already happened, and all I have to do is tell the story as it unfolded, as directly and simply as possible. Otherwise, there’s nothing easy about it.

Describe your morning routine.

I’m an early riser, for one thing. This started back when our kids were small. My wife and I would get up at 4 a.m. so that we could have a couple of peaceful hours before they woke up. That pattern has continued. I get up, make coffee, and while it’s brewing I do 50 sit-ups. Then, with a cup of coffee in hand, I go into my wife’s home office to the secret Oreo drawer, where I grab a single Double Stuf Oreo (yes, that spelling is correct) and then I sit down either to write or, if I’m in the research phase, to read documents or other relevant materials.

On a bad day, where the writing goes hard, or I’m just in a lousy mood, I allow myself a second Oreo. I work until breakfast time, c. 7 a.m., at which point I’d hang out with the kids for a bit, before they went off to school. Now, with our youngest newly off to college, I hang out with my wife, or read the paper, or maybe go out for breakfast. I start work again around 8, and soldier on through the day. Since I loathe the tedium of gym workouts, I take breaks for tennis with my eclectic group of tennis pals. My main tennis connection is a prominent rabbi who periodically has to halt play to arrange a funeral. At day’s end, I’ll go food shopping. I’m the chef of the house. It’s a terrific relief from the obsessions of the day.

Your latest book deals with Nazi Germany. It seems that readers and writers have an endless fascination with the Second World War. What do you think it is, abstractly, that makes this period so absorbing?

I often wonder about that. I do think it’s partly because the Nazis and Hitler present a clear example of unalloyed evil of a magnitude that remains, even to this day, unfathomable—and as such it appeals to us in the way the darkest fairy tales did when we were kids. Of course, those among us who experienced the nightmare first-hand bring a different kind of interest. I’ve met many Holocaust survivors who find the era infinitely compelling, because they have this deep hunger to understand how it all could possibly have happened.

You travel extensively in preparation for writing. Do you feel that being on-site is integral to good history writing?

Traveling to the scene of the crime, or whatever, is absolutely crucial. It’s funny, but I’ve been asked numerous times by readers whether I ever went to Chicago in the course of researching my Devil in the White City, about the Chicago Worlds’ Fair of 1893 and the serial killer who used it as a lure. I traveled there often, both for hard-core research, but also to absorb a sense of the city and, especially, Lake Michigan, and to get a sense of how the light plays across the landscape. I deliberately went to Chicago in all four seasons. What stood out for me was how much the lake colors life in the city. The lake is alive, and constantly changes hue. Sometimes it’s calm, sometimes incredibly rough; and when the lake is frozen, the swells cause the ice to heave in a strange and rather melancholy way. Had I not gone to Chicago, I’d have missed that completely. As a result, the lake is a kind of minor character in the book.

For my latest book, In the Garden of Beasts, I traveled to Berlin, and once again discovered something I could not possibly have grasped without being there, and that was the fact that all the nodes of action in the book—the ambassador’s residence, his office, Gestapo headquarters, the Reichstag building, and so forth—were within a brief walk of each other, all clustered around the eastern end of the Tiergarten, Berlin’s central park, the only place in 1930s Berlin where one could feel free from eavesdropping. One result of that visit was the title of the book, Garden of Beasts being the literal translation of Tiergarten.

Is there anything distinctive or unusual about your work space? Besides the obvious, what do you keep on your desk? What is the view from your favorite work space?

First of all, my office is tiny. I think most people would be shocked if they came to my home and saw it. It is, in fact, the former makeup room of a gorgeous local TV newscaster. I keep a neat desk. Clutter makes me anxious. I’ve got a lot of photographs of my wife and daughters, and various toys, including two Nunzillas, a Frederick the Great action figure, the severed head of a Ken doll, and a very lifelike copy of the kind of rat that once spread the bubonic plague but that now my wife and I use to try to terrorize each other. I’ll quietly spirit the thing off and tuck it, say, into the sleeve of one of my wife’s blouses so that at some later point, when she least expects it, this rodent will fall out onto the ground and hopefully terrify her. She will then, at a time of her choosing, tuck it, say, into my carry-on bag just before I leave on a research trip. Even though we both know the rat is out there, we are invariably startled. We’ve agreed, however, to never ever deploy the rat in a moving car.

What saves the office, given its tiny size, is a tall bank of four windows that look out to the north-northeast. In winter, when the leaves fall off the Japanese plum just outside my window, I get a lovely view of the North Cascades, a snippet of Lake Washington, and the concatenation of intervening hills. In spring, the plum goes wild and blossoms so intently that it’s almost hard to look at. The office is gloriously quiet, and always nice and cool, given the ambient Seattle climate and the orientation toward the north. Now and then a pair of eagles will soar past. I love the rainy windy days of fall when thousands of crows populate the near landscape, cawing and scowling. My middle-daughter used to rush out onto the adjacent balcony and shout out, “Fly my pretties!” This gathering of crows is really very impressive, very end-of-daysish. Sarah Palin should visit.

What is something you always carry with you?

My draft card, in my wallet. So I, at least, never forget how this country can blunder into stupid wars. The card is a little worn now, owing in large part to the fact that one afternoon my middle daughter and I flipped a canoe in Lake Washington, with my wallet still in my back pocket. I never went to Vietnam, by the way. By the time my number was picked, in a televised draft lottery, the war was winding down. I was number 60, as I recall. But I never even had to show up for a physical.

Tell us a funny story related to a book tour or book event.

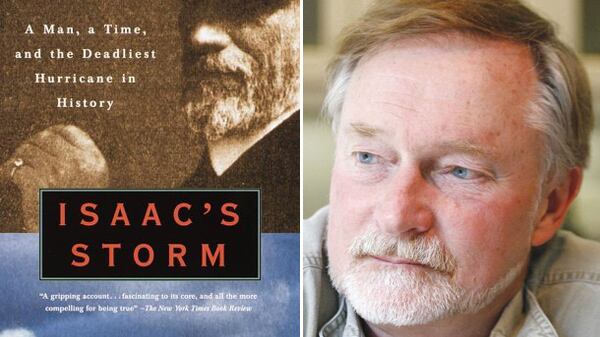

I was in Kansas City, making a stop at a very large chain bookstore during my tour for Isaac’s Storm. I arrived at the store with my media escort. His job was to be much more forward than I, and to ask the store to gather up all its copies of my book so that I could sign them, the point being that once a book was signed, it couldn’t be returned to the publisher. Also, there was always a benefit to be had by discreetly leaving a pile of books on a table or counter at the front of the store for book shoppers to see. My escort asked where we might find the book, which essentially is about the giant hurricane that destroyed Galveston, Texas, in 1900. The clerk said it was in “earth sciences,” not the most positive of signs. So, we rode up an escalator—a very long escalator—and found the book. My escort tucked all eight copies under his arm, and we headed back to the escalator. I got on first. My escort, with the eight copies, followed. A clerk got on behind him. The clerk saw all those Isaac’s Storms under his arm and said, “Phew, I didn’t think anybody was going to buy that book.” My escort looked at him and deadpanned, “Well, I’d like you to meet the author.” I always think of it as the escalator of sighs. A very long quiet ride followed.

But lots of funny-ish things happen on tour. Once a guy introduced me at a big talk, with about 5,000 people in the audience, and as he spoke it became clear to me, if not to anyone else, that he had pulled biographical material off the web for a different Erik Larson, apparently a University of Kansas professor. At another event, the sponsors obligingly sold copies of my books—as well as a number of books written by a novelist with my same name. (Note, however, that this was not nearly as strange as when I received a check meant for that same novelist, sent by a newspaper as payment for an op-ed he’d written.)

And of course there was the time when I visited a large bookstore in Florida for the last stop on my Isaac’s Storm tour, which had been very successful: The store had gone all out. Forty chairs. Brochures in each chair. And no one showed up. Absolutely no one. Which, as all writers will agree, is at least infinitely better than having one or two people show up. But look, I’ve been lucky in this respect. My friend Tony Horwitz, while touring for his book “Confederates in the Attic,” had Civil War reenactors show up with live vintage weapons, including on one occasion a large cannon.

But I’m grateful to have tours. As one of my media escorts, the great Bill Young of Chicago, always says, “There’s only one thing worse than a book tour—and that’s not having one.”

Tell us something about yourself that is largely unknown and perhaps surprising.

The first presidential candidate I ever voted for was Nixon.

What advice would you give to an aspiring author?

If you’re serious about it, you need to do it every day of the week. But never binge-write. A lot of would-be writers wait for inspiration, then write for 10 hours straight, with the result that the next morning they’ve got nothing left. I always advise writers to work in manageable, relatively short periods, and always to stop at a point where they know they can pick up the next day. I’d also quote my favorite maxim: if you don’t ask, the answer is always no. If you don’t send that short story to The New Yorker, one thing is certain, it will never be published in The New Yorker.

What would you like carved onto your tombstone?

“Wish you were here.”