Rarely has a book that’s this much fun to read touched on so much ethnic anxiety. Jewish Jocks: An Unorthodox Hall Of Fame is a new collection of essays on Jews, sports and Jewish athletes that’s destined to be a perennial birthday and bar/bat mitzvah present. The question is whether it should be. As a piece of writing, the answer is a definitive yes. As an occasion for tribal self-reflection, the answer is—eh, it’s complicated.

Editors Franklin Foer and Marc Tracy, both of The New Republic, start out their collection with a falsehood: “It would be absurd to ask us to enjoy sports without engaging our Jewishness as it would be to ask us to live our lives without engaging our love of sports.” Stop right there, because no one's asking you to do that, Jew or gentile. Philip Roth long ago emphasized the centrality of sports to Jewish life by having a character in The Counterlife proclaim that "Not until there is baseball in Israel will Messiah come!" And if any gentile thinks Jews and sports don't mix, it's pointless to engage that kind of bigotry. Let's not over-think this.

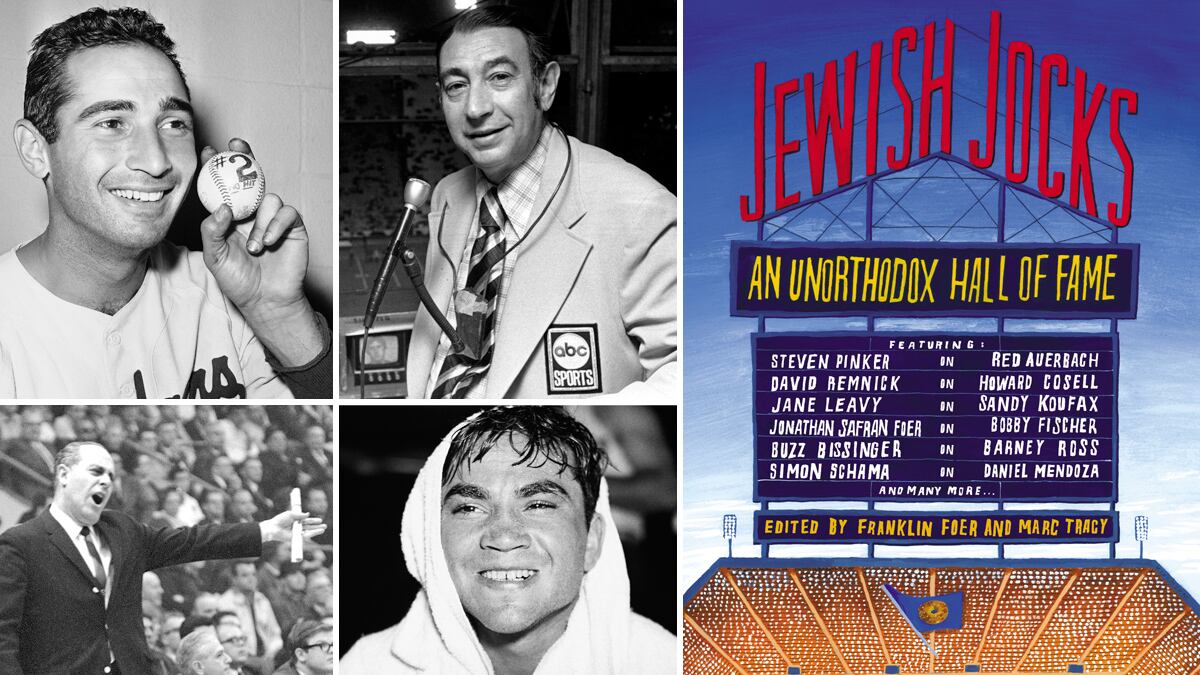

The book elegantly recovers from that early stumble. (To get the disclosures out of the way: Foer fired me from a job that Peter Beinart hired me for, so he’s not my favorite person.) Tracy offers a warm, lovely essay about the forgotten Dirk Nowitski-like forward Dolph Schayes, now an octogenarian whom he occasionally calls for a chat. Jonathan Safran Foer Jonathan Safran Foers Bobby Fischer. But the highlight reel comes from Joshua Cohen, who tells the unbelievable story of Helene Mayer, a Jewish fencer who actually competed for Hitler in the 1936 Olympics. When Mayer silvered, “she, with that long limb, gave the Nazi salute—memorable, public, captured on film.” You come away from Cohen’s essay wanting to read an entire book about Mayer. And of course there are chapters covering the classic Jewish sports heroes Hank Greenberg, Sandy Koufax and Sid Luckman.

Not all of the choices made in the book are as successful. Buzz Bissinger writes a four-page sentence that ruins a requiem for welterweight Barney Ross. David Leonhardt is too soft on MLB commissioner Bud Selig, of whom the best can be said that he didn’t single-handedly compromise baseball’s integrity. George Packer excuses the serial obnoxiousness of Dallas Maverick’s owner Mark Cuban on the grounds that “if being a billionaire in America means anything, it’s that you don’t need to control yourself.” Not exactly Good For The Jews.

But there’s a bigger problem with Jewish Jocks. The book is weighted toward nostalgia for an earlier era—namely the first half of the 20th century, when prejudice barred most professional avenues for Jews and accordingly raised the stakes for Jewish athletics. By the time Foer and Tracy get current, they mostly give us profiles of upper management, competitive eaters, ping-pong champions and sportswriters. (Seriously: why no profile of White Sox third baseman Kevin Youkilis, probably the most visible Jew in contemporary sports?) What does that mean? If an inescapable premise of the book is that Jewish athletes need recognition, then the book ought to do a more thorough job of addressing the implications of their latter-day absence, before an anti-Semite steps into the void with a few theories.

There are any number of ways to address that absence. Here’s one: It means nothing. Nothing about who we are as a people or who we are as individual Jews follows from our endless cataloging of tribespeople in sports, crime, high finance, media or government war councils. It only reveals the anxieties of the self-appointed ethnic actuary. True, it can be fun to know that this-or-that athlete is Jewish. But if your Jewish son or daughter started to internalize the invisibility of Jewish athletes, you would probably want to instruct him or her that role models don’t come from just one community. It’s a short step to saying that Jewish athleticism is an indicator of Jewish virility, and before you know it you’re in the briar patch of self-hatred. And that’s an unfortunate subtext of this book, so much so that the editors discuss foreskins in the Greek gymnasia during the very first paragraph of their introduction. Guys: relax.

Jewish Jocks punts on fraught identity questions, but the exhumed stories of weird, crazy boxers; gangsters fixing sports bets; and Hezbollah’s enthusiasm for the wrestler Goldberg more than cover the spread. Best of all, a current tale of heroism vindicates the book. Adam Greenberg had his career ended in 2005 in his first at-bat by a fastball to the head from Marlins hurler Valerio de los Santos. While it came too late for Stephen J. Dubner’s profile of Greenberg to address, Greenberg stepped back to the plate earlier this month, thanks to a one-day contract from the Marlins. Greenberg struck out against knuckleballer R.A. Dickey, but he reminded everyone of the theme that Jews and sports inescapably share: redemption.