It’s 5:30 a.m., and the Monterey, Calif., coastline is awash in aqua, green, blue, and brown, similar to the pattern of the multicolored blouse worn by Rosemary Malone Cleveland. As we navigate the sharp turns along the 101 Freeway past Gilroy, “The Garlic Capital of the World,” the 56-year-old grandmother is feeling a bit anxious, a bit like a high-school girl just minutes before meeting her prom date.

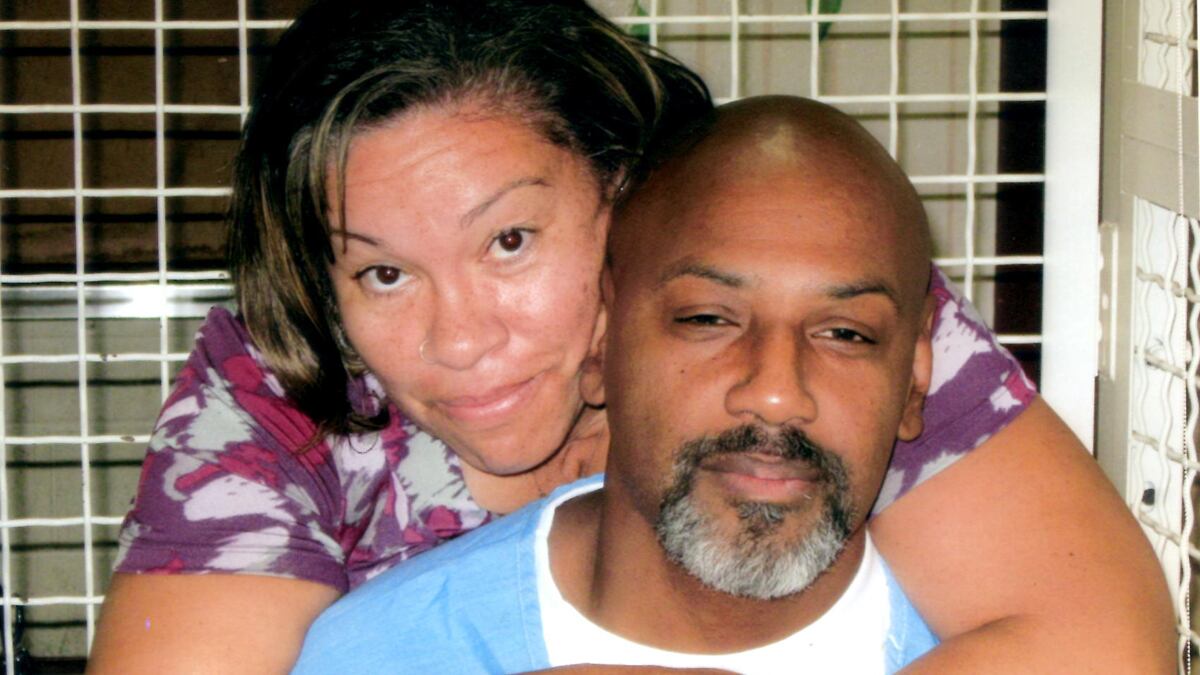

“I couldn’t get my hair right this morning,” says Rosemary as she tugs on her honey blonde locks with hints of gray. It’s been almost one month since Cleveland has taken the 127-mile ride to San Quentin State Prison’s death row to visit her husband of six years, Dellano Cleveland. “I feel like this every time I go visit him. Every time I cross the bridge I get butterflies, like it is our first date,” she says.

Their relationship is hardly a fairytale romance. Cleveland, who was sentenced to death on Dec. 19, 1991, was allegedly involved in the drug-related murder of two men who were shot execution style as they knelt in front of a mirror in a Pomona, Calif., motel room. Cleveland and Rosemary met on death row after Rosemary visited her brother, Kelvin Malone, there before he was extradited to Missouri, where he was executed in 1999 for an alleged multi-state murder spree.

“I try not to get excited when he says he will come home,” she says matter-of-factly. “I lost my brother that way.”

Rosemary, who lives in Monterey with her five Yorkshire terriers, a tea cup Maltese, a pit bull/Lab/boxer mix, and a yellow-headed Amazon parrot, makes the trip to San Quentin twice a month to see her 49-year-old husband, who she affectionately calls Blue. “He doesn’t want me to get burnt out, but it is part of my life,” she says. “I can’t walk away from it.”

This Sunday, Rosemary can’t help but be a bit more anxious than usual about her visit. Voters in California are about to decide on Proposition 34, the measure that would repeal the state's death penalty in exchange for life in prison without the possibility of parole. In April, Connecticut became the 17th state in the nation to repeal the death penalty.

Support for the ballot measure has increased rapidly. According to the latest Field Poll, 45 percent of Californians say they will vote in favor of Proposition 34 while 38 percent will vote against it. Seventeen percent of voters reported they were undecided. In September, only 33 percent of Californians were in favor of the proposition and 51 percent said they would vote against it, according to a poll by USC Dornsife/Los Angeles.

What is appealing to some voters is the idea that Prop. 34 will save $130 million annually, and the money will be spread to local law enforcement agencies to hire more detectives and clear up homicide and rape backlogs.

“As former secretary of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation and former warden of San Quentin State Prison, where I oversaw four executions, I know what works and what does not. I can tell you, without question, California’s death penalty is all cost and no benefit,” Jeanne Woodford, a Prop. 34 proponent, said in a statement Monday.

For Rosemary, the idea that her husband would be spared execution in exchange for life in prison is—perhaps surprisingly—of little consolation. “It is bittersweet,” she says, as she clutches her stomach and shifts uncomfortably in the passenger seat because of a recent hernia operation. “It is still murder no matter what you call it, but life without the possibility of parole is a slow death. I want him home so badly.”

Ironically, many death row inmates and their significant others want to see the measure defeated—in part because it would mean that a large chunk of funding for lawyers and investigators who could help prove their innocence would evaporate. Many of the prisoners would rather take the chance of being executed than lose their lawyers. Natasha Minsker, an American Civil Liberties Union policy director who is running the campaign to pass Prop. 34, says that “a lot of death row inmates feel that by having lawyers and a legal team, it gives them hope, even if they aren’t innocent and there is no chance they will get out.”

Minsker says one of the main reasons for repealing the death penalty is that it simply doesn’t work as intended. “Killers are walking the streets,” she says. “If you are looking to reduce the murder rate, the best thing to do is to catch them quickly and get them off the street. I think most people don’t think the death penalty is a deterrent because it takes 25 years to go through the appeals process and you are more likely to die from old age.”

Case in point: California has sentenced 900 people to death and carried out just 13 executions since 1978. Death row inmates already are more likely to die of old age, cancer, or suicide than by the executioner's needle.

Even so, the death penalty has plenty of ardent supporters, even in liberal California. “I think the death penalty should be enforced in California,” says Tyler Izen, president of the Los Angeles Police Protective League. “The fact we aren’t doing something right isn’t a good reason to throw it out. We need to do a better job of enforcing it. I am concerned that the argument that it saves money to get rid of it is resonating with people who have not been affected by a violent and brutal murder or think that money trumps doing the right thing. ”

Izen, a former LAPD detective, says that the 724 inmates on death row deserve to die for their vicious crimes. “I don’t think certain killers who murder police officers, children, husbands, and wives in cold blood should be able to walk the same earth they prevented other people from walking,” he says.

It’s 9 a.m., and San Quentin State Prison looms in the distance, a short drive across the John F. McCarthy Bridge. A small smile is beginning to spread across Rosemary’s face. The butterflies are back. Instinctively, she begins to look through a clear plastic purse she calls her “prison purse” to make sure she has all her necessary items. Drivers license. Check. Dollar bills. Check. Quarters. Check. Inside her purse, she keeps needles, thread, scissors, and a piece of cloth she can quickly sew onto her blouse if a guard thinks it’s too low cut.

A few minutes later, she pulls into an outdoor parking lot at the gates of San Quentin, where she enters the visitor’s check-in station. She is greeted by name by two female guards before she goes through a metal detector. “We were wondering who this woman was who was on Dellano’s list,” teases one of the female guards as she looks toward me. “We thought he might be up to no good.”

“She’s with me,” laughs Rosemary.

The visitor’s room—which is, perhaps ironically, located next door to the death chamber—is filled with 15 small 8-feet-by-4-feet cells. The cells are filled with inmates wearing blue jumpsuits who are talking or playing scrabble or dominoes with their wives or girlfriends. “Before, it was like an auditorium,” she says about the cramped space. “It was neutral ground. No one fought. They put the cages in there because they allowed two people who didn’t like each other in, and they got stabbed.”

Blue, who is already sitting in one of the cells, hardly has time to say hello to his wife before she darts off toward the vending machines and pulls out her dollar bills and quarters. Within minutes, she has filled a tray with piping hot hamburgers, a chicken burger, and a cheese sandwich, along with a bag of potato chips and three bottles of water. The guard opens the cell and lets us inside. He attaches a large lock to the door and snaps it shut, locking us in the cell.

Blue, a muscular man who stands 6-feet-5 maintains his innocence and says he is against the death penalty—but he isn’t in favor of some of the conditions set forth in Prop. 34. “I want it repealed,” he says introspectively. “I appreciate the sacrifices. They don’t want us dead. But there are innocent people that need to prove their innocence. Life without the possibility of parole is so much better, but if you are trying to prove your innocence from your trial, you are pretty much up shit’s creek. We aren’t begging to be set free. We want to prove our innocence. Some of these people may be innocent and we still have to fight for them.”

If Prop. 34 passed, death row inmates would still be allowed to appeal their convictions in state court, but except in rare situations they would not be allowed lawyers to file their habeas corpus petitions; those petitions raise evidence the trial court didn’t get to hear, and can be heard in federal court once state appeals are finished.

Blue, who eats a hamburger prepared for him by Rosemary, says he lost his appeal battle with the state and now his only recourse is with a habeas corpus petition. “We have no faith in the California system,” he says. “With the feds, we feel they will really look at our case and apply the law. We believe federal judges apply the law and stick to the law.”

“I have been a victim of the state court,” he says. “California courts ignore the evidence and violate their own rule of law.”

Also, Blue thinks that if Prop. 34 passes, the money saved shouldn’t be given to law enforcement. “They always give grants to law enforcement,” he says. “They don’t give the inner city kids a chance. If you don’t give kids a chance they will do what I did. I graduated from Youth Authority.”

Blue says he grew up in Pomona, Calif., idolizing the gang life and the quick money that came along with it.

“Growing up around people with drugs and cars were cool,” he said. “They represented the neighborhood.”The inmate says that, contrary to what Prop. 34 proponents might have you believe, life for death row inmates is hardly cushy. “Prop. 34 people say we get special privileges such as attorneys, cable television, Internet, and food brought to us on hot trays,” he says. “It is not true. We get food that is so distressed you can watch it rot. The only cable we get is the wire.”

He adds: “We don’t have the amenities people think we have. There is nothing personal about these cells. We walk everywhere in handcuffs.”

Regardless, Blue says moving away from death row would be a hard adjustment. “You spend 20 years by yourself, and now you have to smell someone else’s feet and feces,” he says.But what’s the alternative? “If [the death penalty] isn’t overturned, they will start the one-drug execution and they will start lining people up.”

At 1:30 p.m., the guard tells Blue that his time for visitors is up. He and Rosemary kiss tenderly as Blue is handcuffed behind his back and taken out of the cell. Rosemary blows him a kiss as he disappears inside the building.

As she walks back to the car, she says: “I hate saying goodbye, but I wouldn’t change it for the world.”