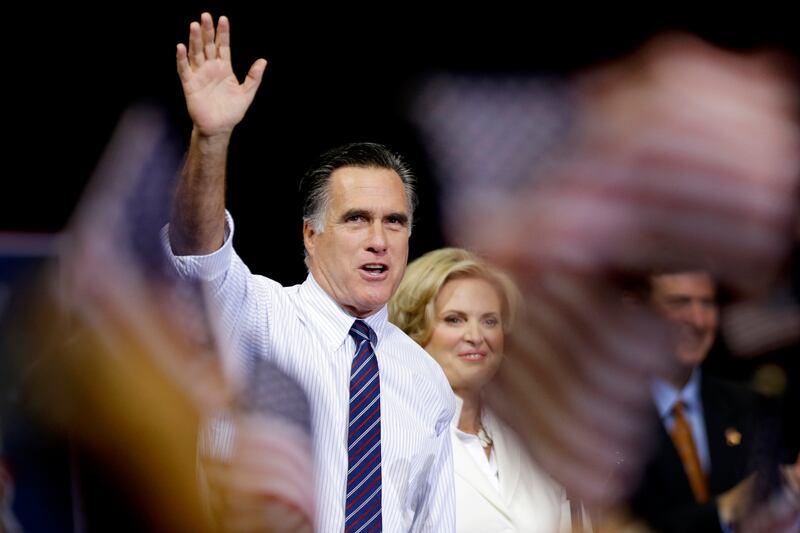

In his final day of campaigning for the prize he has chased for six years, Mitt Romney is playing the bipartisanship card, accusing President Obama of stiffing the opposition party.

By contrast, Romney told audiences on Monday, as he raced from Florida to Virginia, Ohio and New Hampshire, that he will work with the Democrats to get things done.

“Instead of bridging the divide between the parties, he’s made it wider,” Romney said. “You hoped the president would bring people together to solve great problems. He hasn’t; I will. We have to be a united nation—out of many, one.”

What is striking about this closing argument is that it flies in the face of what transpired in Washington for the last four years—and casts Romney in a different role than the “severely conservative” ex-governor he had pitched in the primaries. In effect, he is trying to hijack Obama’s theme from the 2004 convention, that there are no blue states or red states, only the United States.

The president, on his last day fighting to keep his job, stuck to his theme that voters have come to know and trust him. Campaigning in Wisconsin, Iowa, and Ohio, he said: “You see the scars on me, the gray hairs on my hair to show I know how to fight for change.” Obama again cast himself as a champion of the middle class, saying: “I’m not going to turn Medicare into a voucher just to pay for another millionaire’s tax cut.” And: “America works best when everybody gets a fair shot.”

The last-minute barnstorming comes as national tracking polls are showing a photo finish: Romney 49, Obama 48 (Gallup and Rasmussen). Obama 50, Romney 48 (PPP). And while the president continues to lead in most swing states, the snapshot remains blurry. Four polls in Ohio give Obama leads between 1 and 6 points, but one (Rasmussen) has him tied with Romney at 49 percent. Similarly, a Morning Call poll in Pennsylvania, long thought to be a safely blue state, has Obama ahead by just 3 points—which may explain why both Joe Biden and Bill Clinton were dispatched to the Keystone State.

The Romney argument on bipartisanship draws on his days as Massachusetts governor, when he was faced with a state legislature more than 85 percent Democratic. For most of the campaign, the Republican nominee barely mentioned his years in the statehouse, to avoid being drawn into a debate over his health-care plan while he was bashing Obamacare. It was his signature achievement in Boston, where Democrats refused to cooperate with him on a number of other issues.

As for Obama’s track record, it’s certainly fair to say he has had trouble reaching agreement with congressional Republicans. But any fair reading of the situation has to factor in a deliberate strategy of GOP intransigence.

Obama’s stimulus law, which included tax cuts favored by the other party, received no Republican votes in the House and three in the Senate. Obama’s health-care law passed with just one Republican vote, in the House—which conservatives routinely cite as evidence of the president being partisan. Obama also agreed after the midterm elections to go along with Republican demands to extend the Bush tax cuts, when he had explicitly campaigned for letting them lapse for wealthy Americans.

It was the House GOP, objecting to a renewal of the debt ceiling, that triggered the crisis that brought the country to the brink of default. As documented most recently in Bob Woodward’s book, the president met repeatedly with Republican as well as Democratic leaders to hammer out the compromise—involving automatic spending cuts and tax hikes—that averted that calamity.

On other issues, including immigration, the president can be faulted for not trying to forge a consensus with the opposition. But mostly he got raked over the coals by his own party for trying too hard to accommodate the Republicans—a practice Obama abandoned only after failing to reach a grand bargain with John Boehner during the 2011 budget crisis.

On the trail, Romney faulted the president for holding no economic meetings with Republican leaders since June—although no one expects Congress to do anything significant in the final months of an election year. Obama could never even get a House committee vote on the jobs bill he proposed last fall.

Romney’s indictment may be little more than shorthand for a president who, by his own admission, has failed to change the culture of Washington. It is the challenger’s way of saying that Obama, however well-intentioned, just hasn’t gotten it done, and that he, as a career businessman, will bring an outsider’s focus and execution to the job.

Obama, by casting Romney as the champion of the wealthy and himself as the protector of the middle class, is returning to the case his campaign began building last spring with its attacks on Bain Capital and on Romney withholding his tax returns. What Obama seems to have dropped in recent days is his “Romnesia” refrain, the argument that his opponent keeps forgetting his past positions. Perhaps that reflects a recognition that Moderate Mitt was getting traction in the polls as many voters felt they were seeing the real Romney—one who wouldn’t make radical right-wing changes.

The tactical decisions, the geographic choices, the attack ads, the gaffes, the hurricane’s impact—all that is about to fade into history. Barack Obama and Mitt Romney have completed their campaign—a hard-fought one, but hardly an inspiring one—and now must await history’s verdict.