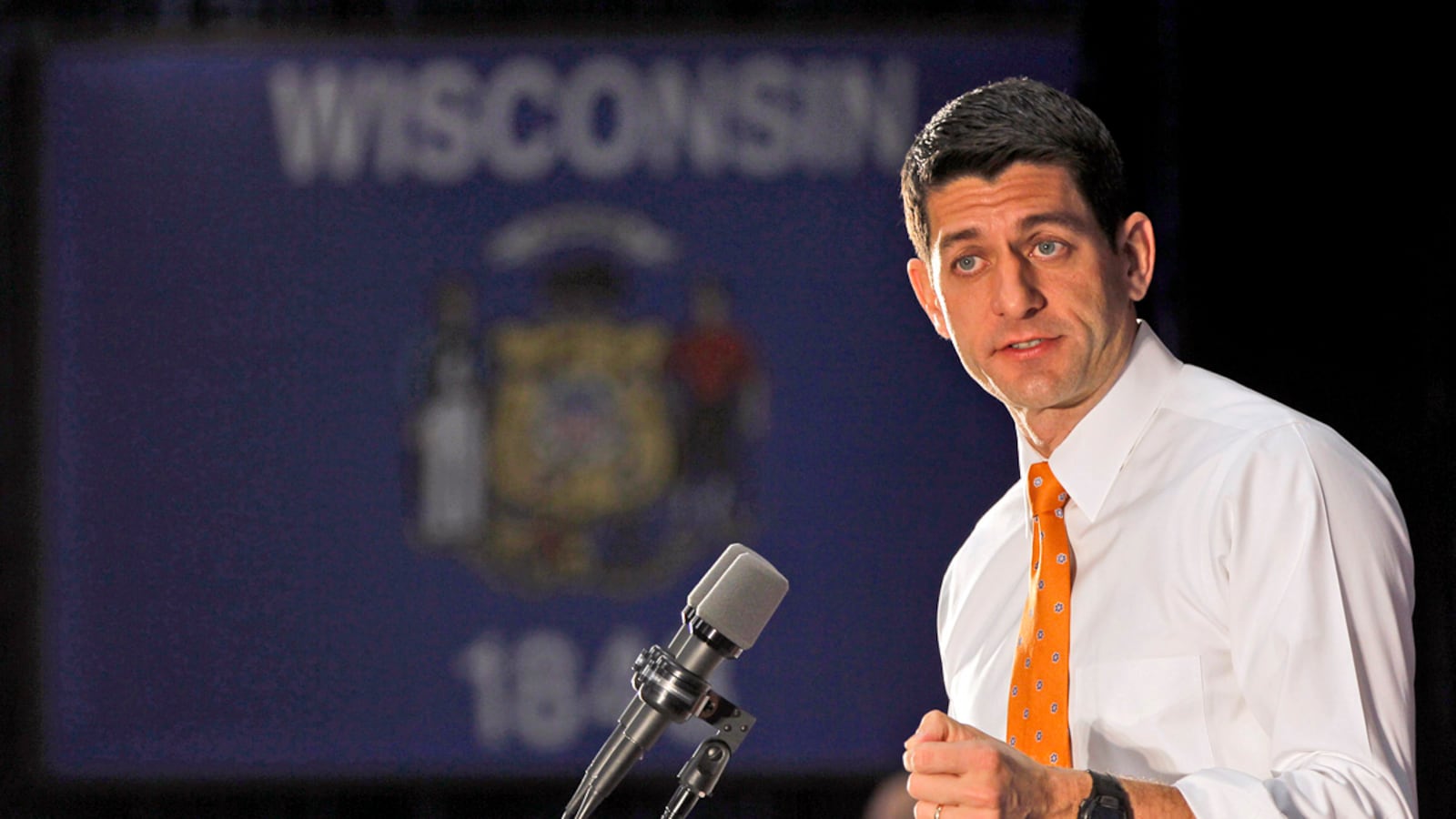

Mitt Romney won plaudits from conservative activists and Beltway insiders alike when he picked Rep. Paul Ryan, the media-anointed Republican budget guru and rising congressional star, as his running mate this August.

The logic behind the Ryan pick was simple: quiet any lingering conservative discontent with Romney’s nomination and recast the presidential election as a starkly ideological choice. But in the campaign’s final days, Ryan was absent from the national conversation, and his impact on the race proved to be something of a dud.

Unlike Sarah Palin, who boosted Sen. John McCain’s standing among conservatives four years ago and simultaneously alienated large swaths of independent and moderate voters, Ryan doesn’t appear to have had a tremendous impact on undecided voters. Republicans were always going to be pumped for the chance to take out President Obama, especially after a monster debate outing from Romney in Denver.

And despite Democratic insiders expressing glee at the prospect of running against the Ryan budget and its proposal to change Medicare into a voucher program, health care was not at the forefront of the candidates’ closing arguments.

Ryan’s quiet finish on the trail is attributable to two things, insiders from both parties say: Romney effectively stepping up and serving as his own best attack dog, and Ryan’s conservatism clashing with the new, moderate Romney of the final month of the campaign.

“There’s a limited list of scenarios where you would’ve had Paul Ryan going out and making the case against Barack Obama harder,” says Rick Wilson, a veteran, Florida-based GOP consultant. “But they were all dismissed after Oct. 3, when Mitt Romney cut off Barack Obama’s head in that debate.”

Republicans were thrilled with the Denver debate, and Romney—both on the stage that night and in his subsequent TV ads—appeared to feel safe to pivot sharply to the center on social issues such as abortion. He ran TV spots in swing states refuting Democratic claims that he would overturn Roe v. Wade. The shift to the middle was calculated to improve his odds at winning over moderate suburban women, who do not tend to be fans of the anti-abortion-rights conservative lawmaker from Wisconsin.

“I think they realized that the problem they were having with women was exacerbated by Ryan’s positions,” says longtime Democratic strategist Tad Devine, a veteran of the Al Gore and John Kerry presidential campaigns. “As Romney tried to move to the middle, the distance between Romney and Ryan on the public record was enormous.” Allowing the congressman to move front and center to wax poetic on policy issues would have drawn yet more scrutiny to those disparities.

Or as Robert Shrum, another veteran of the Gore and Kerry campaigns, puts it, “The pick was inconsistent with Mitt’s moderate makeover, so [Ryan] had to go into the background.”

Operatives from both parties believe Ryan was genuinely committed to the ticket and did everything he could to help Romney win. But keeping a low profile in the campaign’s final days had the added bonus for Ryan of creating some distance from Romney’s looming defeat, setting the congressman up for an even brighter future in conservative politics.

“He’s immediately on shortlists for 2016,” says Republican strategist Rob Stutzman. “What he doesn’t have, and will have to start building quickly, is a national political organization.”

Thanks to a few weeks of barnstorming in states such as Iowa and Florida—neither of which appeared late Tuesday night to have voted as Republicans had hoped but which remain a sure bet to play a significant role in choosing the next Republican presidential nominee—Ryan is well on his way.

What’s more, Ryan was careful to do what Joe Biden did four years ago and run for reelection to Congress even as he joined his party’s national ticket. Early returns showed a tighter race than might have been expected in Ryan’s Janesville-based House district, but his name is bigger than any one race now.

“Paul Ryan is now a brand who exists outside the confines of the congressional universe,” says Wilson, the Florida-based GOP operative.

Unlike Palin, who was content to resign as Alaska governor and cash in on lucrative book deals and speaking gigs, Ryan is likely to do everything he can in the coming months to remain near the levers of power in Washington. Going forward, he has a reservoir of good will among the conservative faithful to lean on in future political endeavors.

“He’s gonna try to move into the leadership void in the party,” says Devine, who knows firsthand what the aftermath of a losing campaign looks like.