Sadiquallah Naim was asleep in his room when his neighbors came knocking on the door of his mud-walled house in a remote village in southern Afghanistan on March 11, in the dead of night.

“The Americans are here,” they said.

Minutes later, the young teenager’s sister, his mother, and his brother were dead, gunned down along with six other adults and seven other children in a rampage that American military officials say came at the hands of an Army sergeant hopped up on steroids and alcohol.

Sadiquallah told his story from a base in Kandahar Friday evening during Staff Sgt. Robert Bales’s “Article 32” hearing, the military’s version of a criminal trial that could result in a court martial and death sentence for the 39-year-old officer and father of two children. Bales, who was on his fourth combat tour overseas, is charged with 16 counts of premeditated murder and seven counts of attempted murder in the deadliest alleged war crime since the conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq began—an atrocity that has added to an already tense relationship between the U.S. and the government in Kabul.

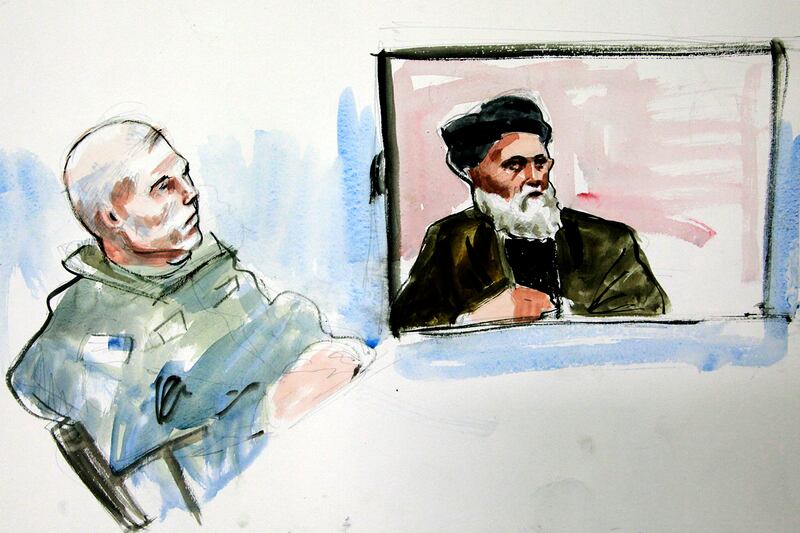

The boy was one of seven witnesses to take the stand at a proceeding that began at 7:30 p.m. Friday and lasted until after 2 a.m. that night, because it took place on Afghanistan time. Two guards and five villagers spoke in graphic detail of the brutal middle-of-the-night attack on their homes and families. Bales sat stone-faced, watching the videoconference feed in a courtroom at the Washington base where he was stationed and is now being detained. His wife, Kari, stayed through the entire proceeding, two rows back.

The hearing was at times impossible to follow, due to problems with interpreters, and the inherent challenge of cross-examining a witness via the Army’s version of Skype. Reporters sat in a nearby overflow room during the late-night proceeding, quizzing one another on whether the witness said he was shot in the “ear” or in his “hair.”

What broke through any language barrier, though, was the horror these villagers experienced that night in March, in tales they retold wearing the unmistakable countenances of anger and sadness.

During the proceeding, which began Monday and included the in-person testimony of fellow soldiers and officers who investigated the massacre, Sadiquallah lent clarity to a question that has come up often in the weeks leading up to Bales’s hearing: was the sergeant alone at the time of the shooting?

Bales’s attorney, John Henry Browne, insinuated in a recent Newsweek interview that some villagers would testify that they saw more than one American soldier during the gruesome spring rampage. None who spoke Friday night either identified Bales directly or mentioned multiple soldiers, though.

They saw just one man, wearing a black T-shirt and camouflage pants, a headlight obscuring his face, wielding an assault rifle with a light attached to it, mowing down men, women, and children as he stalked from house to house, room to room.

Sadiquallah’s neighbors told his family that night, “They shot our family”—a woman he knew well “told us he killed our men,” the boy testified—before an American soldier burst into his room. He ran, he said, and hid behind a curtain, but was shot in the ear by one of the many bullets that were being fired in his house.

“Were you scared?” the military prosecutor asked the boy. “Yes,” he replied, his face bowed. “How many Americans did you see?” the officer asked. “One,” answered Sadiquallah.

The boy’s 14-year-old brother, Quadratullah, took the stand next, smiling and curious, until the officer asked him to remember that night, and his face fell. He testified that a woman with most of her clothes ripped off had come running to their house, screaming, “They shot my man! They shot my man!”

Then came the American soldier, shooting indiscriminantly, scattering Quadratullah’s eight brothers and sisters. They yelled at him in Farsi, he said, again and again, “We are children! We are children!” But that did not quell the rampage, said Quadratullah. Two of his sisters wound up dead, along with his mother, before the soldier disappeared into the darkness.

Quadratullah hopped on his motorcycle, he said, to try to find help for his wounded family members, including his father, shot three times. Other villagers piled the dead and the living into a car and drove to Bales’s base. By the time the sun came up, there were droves of Afghans there, also with dead bodies in their vehicles. They had considered burying the victims, another witness testified. But someone said if they did, such killings would only continue.

The next day, Quadratullah said, he followed the soldier’s footsteps from his house. They led straight to that base.

Next, Quadratullah’s father, a farmer named Haji Naim, took the stand, in a long white beard and turban. He awoke to dogs barking and gunshots, he said, and turned on a kerosene lantern to see what was going on. He thought maybe the Afghan National Army had come to the village, searching for someone.

Moments later, an American soldier stormed into his room, Naim said. He didn’t get a great look at the soldier’s face, just “the light on his head.” Then, “he just started shooting,” Naim testified, pointing at his own neck, his collarbone, and his shoulder before the interpreter translated: “He shot me right here, and right here, and right here.” The shooter was only a foot or two away from him, Naim said.

“My son told him, ‘What are you doing? What are you doing?’ He didn’t say anything. He just stood right here, shooting at me.”

Bales’s military attorney objected to this venue and the videoconferencing at the hearing’s outset. He said that two of the witnesses had passports and wanted to attend the hearing in person. “Objection noted,” said the Army’s investigating officer, Col. Lee Deneke, the hearing’s version of a judge, before proceeding.

Though the video relay made things confusing, it didn’t dampen the drama. A man named Khamal Adin testified that he came to the village from nearby Kandahar City that night after his cousin, who lived there, called him on his cellphone. Adin arrived to his cousin’s house to find bodies, stacked atop one another and smoldering from a fire.

Adin saw his cousin’s mother by the door, he testified.

“She was shot on her head, and the brain was outside,” Adin said, his arms folded, frowning. “I had not seen her other injuries. When I grabbed her, half of her head fell down, with her eyes on the ground.”

The man spoke in generalities, of the stack of bodies he saw, of separating the males and females from the pile and dragging them outside, to be driven to the Army base.

“They were all shot up on the heads,” Adin said. “One woman, her brains were still on the pillow.”

The prosecutor asked him to slow down.

“I’m sorry, but I want to ask you about the bodies, one at a time,” the officer said. “I would like to ask you about the children.”

One by one, Adin described their bodies. Everybody was shot in the head, he said. One was split in two. They were all burned. A 4-year-old was shot in the face, and it looked like she was kicked there, too, he said, “because I saw some foot shoe mark on her face.” A 3-year-old was also shot in the face, he said, also with a shoe print.

Then he talked of the baby, Nadia, who the officer said was between 18 months and 2 years old.

“Did you see her wounds?” the officer asked.

“No, I have not seen her wounds,” Adin said. “It seems like she was just grabbed alive from her bed and thrown on the fire.”

Adin was asked if the bodies were naked, and he said yes. He asked if it appeared that their clothes were removed, or if they had burned off in the fire.

“Nobody was alive that we could ask if the clothes were burned off if they were naked before they were burned,” Adin said.

When he finished testifying, Deneke thanked him, and Adin rose.

“This is my only request,” he said, “to get the justice.”