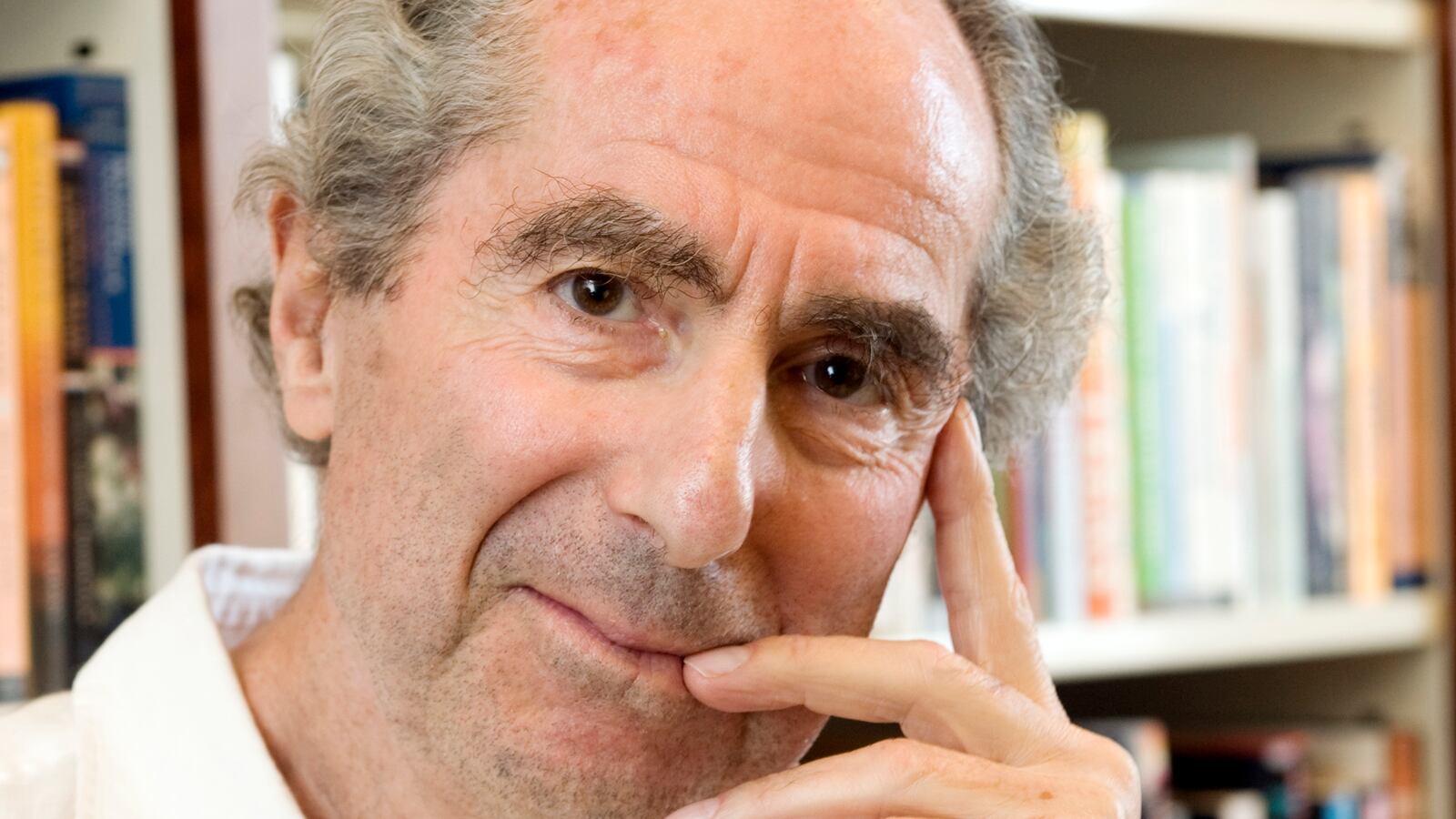

Philip Roth’s last word—that he’s done writing—is typically smart and self-conscious. It’s all about Roth—how could it not be?—but it also conceals a measure of wisdom about the hazards of an inevitable literary diminuendo.

Only a writer so preternaturally alert to the fickle processes of fiction could have quoted the heavyweight boxer Joe Louis to such effect, namely, that he had done the best he could with what he had. His admirers will struggle with dismay and disbelief. Roth always seemed to be invincible. Indeed, he has so often breathed new life into his art that it’s a shock to hear that his last novel, Nemesis, will definitively be his last.

Roth, who is now 79, has had so many literary lives. First, there was the wunderkind author of Goodbye, Columbus, a landmark postwar debut. Next came the enfant terrible of Portnoy’s Complaint, the late ’60s comic sensation, dubbed “a wild-blue shocker” by Life magazine. Then there was the experimental satirist of Our Gang and The Breast. In young middle age, Roth continued the exploration of his turbulent self in My Life as a Man and The Professor of Desire. Later, he nurtured a more secure literary alter ego in his acclaimed Zuckerman novels.

But the best was yet to come. In 1997, when Roth was in his mid-60s, he embarked on a sequence of novels, well-wrought explorations of America’s recent past, that were hailed by critics on both sides of the Atlantic. Here—in American Pastoral, I Married a Communist, The Human Stain, The Dying Animal, and The Plot Against America—was a vigorous refutation of Fitzgerald’s bitter aside that “there are no second acts in American lives.” No writer in living memory has had such an extraordinary late-season surge. Lately, Roth’s mood had become valedictory (Exit Ghost) but still defiant (Indignation). And now he has, like Joe Louis, hung up his gloves.

It’s a good retirement, as Roth himself must surely know. Literary lives generally end badly. Poor health, rejection, and neglect, even madness, are the most likely final chapters. Late work is often inferior and last books just downright embarrassing. In the past, death has been the best career move, especially for young writers (Keats, Dickinson), but also for novelists mid-flight (Stevenson, Lawrence, Orwell). Dickens died of a stroke aged 57, in the middle of Edwin Drood. His near contemporary, Herman Melville lived on in worsening debt and obscurity, until 1891, forty years after the publication of Moby Dick.

Such retirement is few writers’ preferred option. The ability to go on telling stories, or at least to make a daily rendezvous with the keyboard, is often synonymous with life itself. In modern times, only a few great writers have been reprieved by the grim reaper. W.G. Sebald died in a car crash in 2001. Ted Hughes died prematurely in 1998. These are the exceptions. For most, there remains that creative rallentando: the thankless treadmill of the book-festival circuit, literary critical interviews, and the recycling of old readings. The pressures of Grub Street play their part, too. A cocktail of vanity, optimism, and defiance, spiked with raw economic necessity, keeps old writers in the game long after they should have bowed out with dignity.

For all these reasons, then, Roth’s announcement, though sad news for his fans, deserves a dignified salute. He joins a very select fraternity, including William Shakespeare who abjured “this rough magic” (the theatre) in 1611, and lived on quietly in Stratford until his death in 1616. Posterity thinks well of him for that. Perhaps Roth, with an eye to his standing on the literary stock market, has made a similar calculation.