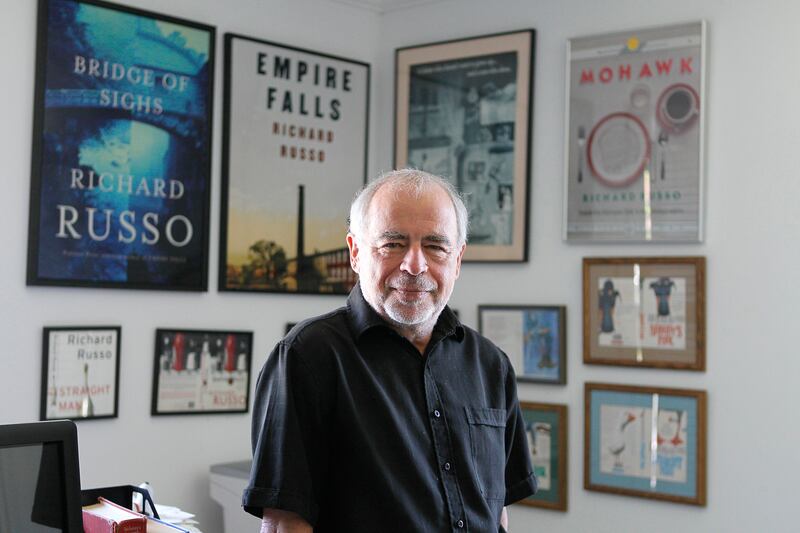

Richard Russo has created a series of indelible portraits of his hometown of Gloversville, N.Y., a fading working-class community in the foothills of the Adirondacks. He called it Mohawk in his 1986 first novel by that name (and The Risk Pool, its sequel), North Bath in Nobody’s Fool (1993), Empire Falls in his 2001 Pulitzer Prize–winning novel, and Thomaston in his 2007 novel Bridge of Sighs. All of his novels are, he says, “snapshots of an America vanishing before our eyes.”

Add his evocative, unsentimental new memoir, Elsewhere, to the list. It’s about growing up in the real Gloversville with his stylish, ambitious, and unstable mother. "From the time I was a boy I understood that my mother's health, her well-being, was in my hands,” Russo writes. “How often over the years did she credit me, or my proximity, with restoring her to health? My rock, as she was so fond of saying, always there when she needed me most. My own experience, however, had yielded a different truth—that I could easily make things worse, but never better." He spoke to me by phone from his home in Camden, Maine.

How were you inspired to write Elsewhere?

John Freeman, the editor of Granta, played a key role. He was planning an issue for Granta about going home. He’d been driving along the thruway, and saw the sign for Gloversville and contacted me on the off chance I might be willing to write about Gloversville the real place, as opposed to the fictional avatars I’d used over the years.

I was vulnerable to the idea. My mother had recently died. John called at a moment I was thinking about my mother’s life and death, and our deep ties to Gloversville, and how my mother and I had so much in common. Nature (we were both obsessive people, I as much as my mother), and nurture (we’d both grown up in this same small town that time doesn’t affect very much). If John hadn’t called right then, I might not have written this book. Over the years I have had very few impulses to tell the truth. This book may have exhausted them.

Reading Elsewhere, I was intrigued by the references to her mental state by people who knew your mother well. Her parents tried to stop her from going with you when you drove to Arizona to begin college, referring to her “condition.” When you were 21 your father told you he couldn’t bear to live with that “crazy” woman. At what point did you realize she was truly unstable?

I didn’t know when we went off to Arizona together. I was 18. I won’t say I didn’t have any clue. I just knew that in the female line of my mother’s family, there was a tendency to what was euphemistically referred to as “nerves,” but amounted to incapacitation, an inability to leave the house. It wasn’t just my mother. My maternal grandmother and her sisters had it too.

When was the first time I realized this was beyond a predisposition to anxiety? I was married. It was only then, when my mother begin to display the symptoms more overtly, that my wife’s family and other people outside the family circle began to raise questions.

Did living in her world affect your vision of reality?

I don’t doubt it. As a kid I was desperate for order and for things to proceed logically. When you’re an only child, you don’t have anyone to compare notes with. I was married and in my late 20s before it dawned on me this was something more serious than nerves.

Toward the end of Elsewhere, you describe your newly married daughter’s diagnosis of obsessive-compulsive disorder. The doctor says that with treatment she will be fine; without it, the disorder “would eat her alive.” How much time did you spend looking back, then, at your experiences with your mother?

I had to reinterpret everything about our lives together, going back to my earliest memories. This was part of the business of writing the book. And the other thing that my daughter’s diagnosis did was, since she got expert help immediately, and was fine, I was overwhelmed with guilt. I had done everything wrong. I had enabled my mother. What she wanted and what she needed were two different things. Later in her life, when I should have investigated her condition more fully, I failed to do that.

What do you think it would have meant if your mother had been able to have treatment? Do you think about who she might have been?

I think about it all the time. She went to her share of doctors, from the time I was very young. Some of them watched her very carefully. But her condition was not even in the medical literature the way it is now. She would have lived an entirely different life if she’d had access to the professional help we have today.

Did you and your mother talk about your books?

We did. As you can imagine, her reaction was mixed. She loved them, but her reaction was often rueful. She recognized my father, her husband, in characters like Sam Hall from The Risk Pool and Sully in Nobody’s Fool. She remarked to me on more than one occasion that she liked these guys better in my novels than in real life. And it mystified her that I could, in writing about Empire Falls, Thomaston, Mohawk, and North Bath, show such affection for the place she felt had circumscribed her life.

Did she recognize herself in the work?

If my mother ever recognized herself in, say, Ned Hall's mother in The Risk Pool, she never said so. She'd sometimes admit to seeing herself in minor characters like Mrs. Gruber in Nobody's Fool, who didn't drive and whose sense of direction was so bad she had no idea how to get to places she'd been going to her whole life.

Was your mother alive when you won the Pulitzer for fiction for Empire Falls?

She was. The Pulitzer and good reviews and good sales were enormously satisfying to her because she did such a courageous job when I was little, and did much of it on her own. She took enormous satisfaction in my success as a writer, as a family man, her granddaughters. The Pulitzer was the high point. On the other hand it was difficult for her to process. She kept saying it’s like it was happening to somebody else. I understood that. I was obviously writing about the Gloversville she knew. Her life’s work was to get me out of Gloversville and away from what she considered to be narrow, small-minded people. Despite the fact that I had won my prize and had the kind of success writers dream of, she felt that as long as I kept returning to Gloversville in my fiction, it probably meant I wasn’t free, and her job remained incomplete.

How were your wife and daughters able to accept your devotion to your mother, how you seemed to put her first?

My daughters treated their grandmother with infinite forbearance and affection. They recognized that she was struggling mightily, even though nobody could put a finger on what it was she was struggling with.

Over 35 years of our marriage, Barbara was willing always to grant me my need not to turn my back on her. I simply could not walk away. Barbara was faced with about as cruel a decision as any woman who loves her husband. There was no cure for whatever ailed my mother that anybody knew about at the time. And as I put it in Empire Falls, “What can’t be cured must be endured.” It was the ground zero of our lives.

What are you working on now?

Robert Benton and I just finished a screenplay first draft. I’m putting finishing touches on a novella, which will come out in January in an online magazine called Byliner. And I’m working on a sequel to Nobody’s Fool called Everybody’s Fool.