Super PACs: in the lead-up to the 2012 presidential election, those two words caused rejoicing among conservatives and dread among liberals. But both sides agreed that the massive influx of private money into the race—suddenly legal after the Supreme Court’s controversial 2010 ruling in Citizens United—would forever change the nature of American politics.

It didn’t quite work out that way.

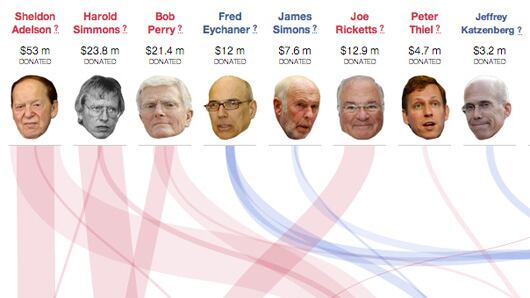

As has already been well documented, enormous amounts of money did, in fact, get spent by private citizens in support of Barack Obama or Mitt Romney or other officials running for office—more than half a billion dollars in all—and yet the biggest donors were in many cases the biggest losers.

The most spectacular failure was perhaps the casino magnate Sheldon Adelson and his wife Miriam, who together put more than $53 million into the pot—including $15 million to Newt Gingrich in the Republican primaries and then $20 million to Mitt Romney once he became the nominee. On Nov. 6, Adelson-backed candidates went 1-for-9.

In the end, the super PACs’ influence was counteracted by several factors: for one, they were forced to pay higher rates than the candidates for ad time, and in our DVR age it wasn’t hard to just tune the TV spots out altogether. In the end, the GOP’s advantage in super PAC spending translated into a loss of seats in both the House and Senate, not to mention the presidency. Given this, the 2016 race seems more likely to be decided by voter turnout, as it was in 2012, and not by a few rich guys with a limitless commitment to their candidate, right?

To the contrary, top political operatives say. In fact, the search for the next Sheldon Adelson is already set to begin.

But why, if they were so ineffective this time around? The current thinking in political circles is that even if super PACs have limited efficacy in a general election, they can have an outsized role in the earliest days of the 2016 primaries. In the months to come, candidates can use the extra campaign funds to boost their name recognition in early primary states, and vault themselves from a second- or third-tier contender into someone making a serious play for Iowa and New Hampshire.

“I don’t think you will see any candidate approaching 2016 without a super PAC behind them,” said one GOP operative who helped run one such group this cycle.

Super PACs played a big role in the 2012 primary season too, but they were like an Italian sports car laced with more high-tech gadgetry than its driver can handle. Instead of boosting candidates in the early days, the PACs did not get fully engaged until late, after much of the voting had already happened, so rather than vault an under-the-radar candidate to the top tier, long-shot candidates like Newt Gingrich and Rick Santorum managed to stay in the race longer.

“It allows someone who is a dark horse to have a few major funders put them on the map, which allows them explode over the course of the primaries,” said Greg Strimple, a top Republican strategist. “It enables someone at the granular level of a campaign, who can’t raise super-sized funds to be in a position to be a major party nominee.”

And in the early states, being “on the map” can make all the difference, as Barack Obama will tell you. In Iowa, New Hampshire and South Carolina, voters frequently tell pollsters they are looking for a candidate who they think can beat the other side in the general election. But success in politics has a way of breeding success, so the sooner candidates can convince early-state primary voters that they are a plausible nominee, the more establishment support is likely to follow.

If there is one thing the 2012 super PAC experiment did get right, however, it is that Santorum, Gingrich and the rest were propelled not so much by outside groups but by outside individuals who provided the bulk of the funding for their run—in Santorum’s case, by wealthy investor Foster Friess, and in Gingrich’s case, by Adelson, a casino mogul.

So as the early positioning for the next presidential race gets under way, the charge for would-be contenders is as follows: Find a rich guy and make nice.

Unfortunately for would-be candidates, there aren’t that many rich people around who are willing to pour cash into the possibly quixotic dreams of a small-state governor or senator. And the existing major outfits, like Rove’s Crossroads GPS and the Democratic Priorities USA, are likely to hold their fire until the general election.

Operatives on both sides of the aisle say that there are likely more potential donors out there for Republican super PACs than for Democratic ones, for at least two reasons: wealthy liberals are slightly more likely to want to power-fund causes than candidates, and for many on the left, the idea of super PACs still has the stench of corruption.

“Super PACs are the drone missiles of the political scene,” said Robert Zimmerman, a prominent Democratic donor who said he hadn’t—and wouldn’t—give money to outside groups. “Their mission is a destructive one, by definition.”

On the Republican side, the top “gets” are considered to be those that were around the last time—Adelson, Friess, the Koch brothers, and Texas home builder Bob Perry. The Democratic side remains less explored, although several operatives mentioned George Soros, former Obama finance chairwoman Penny Pritzker, and entertainment mogul David Geffen.

“Major donors like that are likely to be more ideological, but there has to be a relationship that develops over time,” Strimple said. “Iowa, New Hampshire, South Carolina are all pretty cheap states as far as media goes, so if you find some guy who willing to put in $15 or 20 million, all of a sudden you become the real deal.”