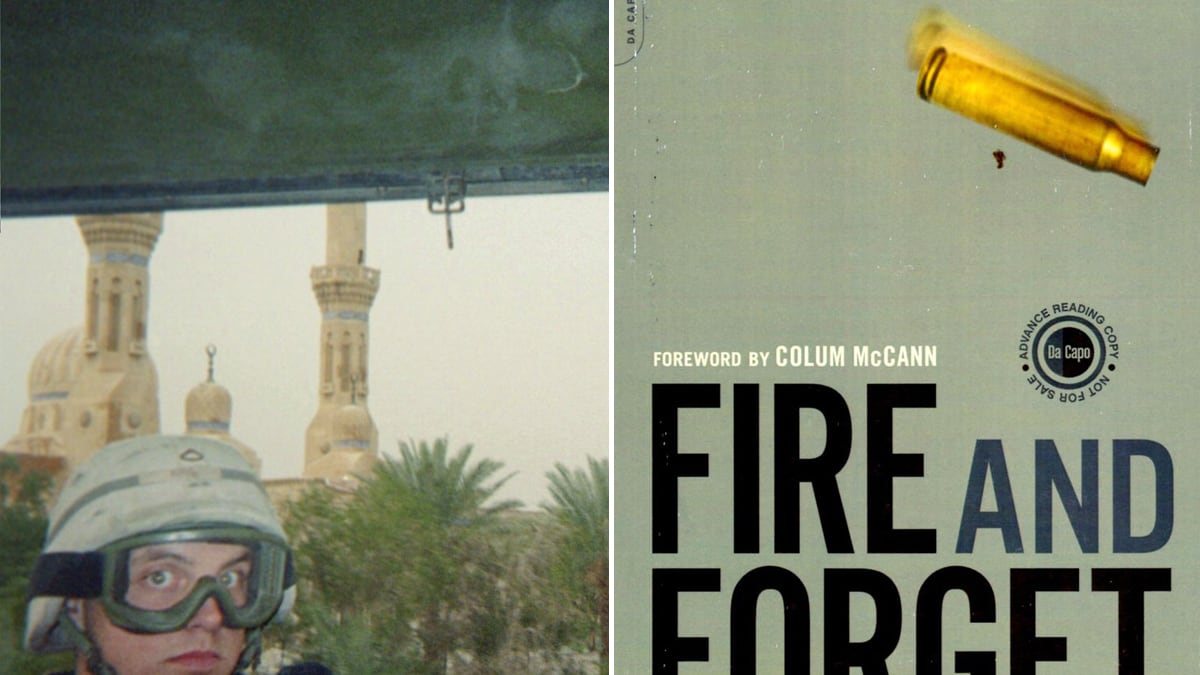

Fire and Forget is the first anthology of short fiction about our post-9/11 wars, and what comes next for those who served in them. It was edited and written by service members who deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan, along with one story by a military spouse. In an excerpt from the collection’s preface, editor Roy Scranton details how the core group that assembled the anthology met in New York.

One thing a vet will always tell you is that it’s never like it is in the stories. Then they’ll tell you theirs.

We convened at the White Horse Tavern, under the glum and bleary eyes of Dylan Thomas, Norman Mailer, and Jack Kerouac. It was a warm March day, not spring yet but with winter fading, eight years and change since we’d invaded Iraq. Afghanistan loomed shadowy behind that, then 9/11, then the Cold War, Vietnam, Korea, World War II, Pickett’s Charge, the Battle of Austerlitz, the conquest of New Spain, Agincourt, Thermopylae, and the rage of Achilles—stories upon stories—stories of war.

We had our own stories to tell, and in each other had found just the right audience to test the telling. There’d be no bullshit, yet we shared among us a subtle understanding that the real truth might never make it on the page. We each knew the problem we altogether struggled with, which was how to say something true about an experience unreal, to a people fed and wadded about with lies. As Conrad’s Marlowe put it, somewhere in another “war on terror”: “Do you see the story? Do you see anything? It seems to me I am trying to tell you a dream—making a vain attempt, because no relation of a dream can convey the dream-sensation, that commingling of absurdity, surprise, and bewilderment in a tremor of struggling revolt, that notion of being captured by the incredible which is of the very essence of dreams.”

There’s always that wobble in war between romance and vision, between reality and imagination, between propaganda and what you lean on to survive. Each story has one ending, the same ending, and it can come sudden, silent, unseen: the street blows up under your feet or a sniper gets lucky. Who knows? Meanwhile, home is a place you lived once, a different person, a different life, and all the people you loved somehow alien. You come to depend on the hard matter of things, because what’s “real” so quickly goes up in smoke.

How do you put that on a page? How do we tell you? How do we capture the totality of the thing in a handful of words? How do you make something whole from just fragments?

We’d met, the five of us, through the NYU Veterans Writing Workshop and other vet events in New York City. There was Jake Siegel, Brooklyn-born, still serving in the National Guard; Perry O’Brien, Airborne medic turned peace and labor activist; Phil Klay, Dartmouth grad and smooth-talking Marine public affairs officer, earning his MFA at Hunter; Matt Gallagher, a rangy westerner, once a cavalry officer in a big blue Stetson and now fighting for vets’ rights with the nonprofit Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America; and myself, college dropout and one-time hitchhiker made good, now at Princeton earning a PhD in English. We came from different places and had different wars, but we shared a common set of concerns: good whiskey, great writing, the challenges and possibilities of making art out of war, and the funny gray zone we found ourselves in, where you shape truths out of fiction pulled out of truth—which might only be the illusion of truth in the first place.

We made a date for the White Horse, where this anthology took root. Over the next year, we collected stories, soliciting, nurturing, pruning, trying to put together something we could feel proud of, something if not representative, at least vivid enough to inscribe on the wars our mark—our signature.

Truth, truthiness, in this mass media cacophony we live in, comes up something for grabs. Well, here’s some. Grab it. We were there. This is what we saw. This is how it felt. And we’re here to say, it’s not like you heard in the stories.

We all have our personal remembrances—to those who didn’t come back and to those who did, but found themselves so weighed down by what happened that they couldn’t make the transition. In a sense, our collection is dedicated to every soldier and Marine who found coming back to the Mall of America stranger, even, than their first time under fire.

We tossed around several ideas, including Did You Kill Anybody? and I Waged a War on Terror and All I Got Was This Lousy T-Shirt, but stuck with Fire and Forget because it seemed to touch so aptly on the double-edged problem we face in figuring out what to do with our experience. On the one hand, we want to remind you, dear reader, of what happened. Some new danger is already arcing the horizon, but we tug at your sleeve to hold you fast, make you pause, and insist you recollect those men and women who fought, bled, and died in dangerous and faraway places. On the other hand, there’s nothing most of us would rather do than leave these wars behind. No matter what we do next, the soft tension of the trigger pull is something we’ll carry with us forever. We’ve assembled Fire and Forget to tell you, because we had to—remember.Excerpted with permission from Fire and Forget: Short Stories, forthcoming from Da Capo Press in February.