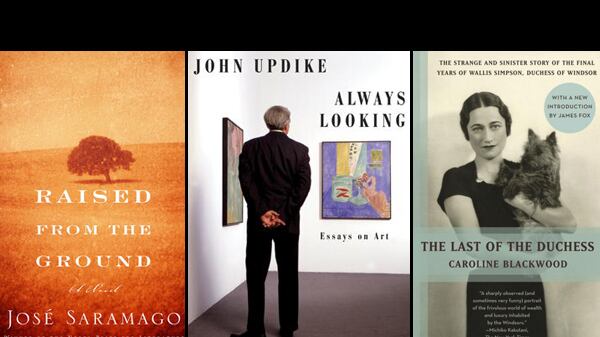

Raised From the Ground By José Saramago

The Portuguese Nobel laureate’s 1980 novel of landless peasants is finally available in English in a translation by Margaret Jull Costa.

Before the workers’-rights struggle began, life for the landless peasants on the Portuguese latifundios was brutal. Laborers were expected to work from dawn to dusk for next to nothing, facing backbreaking labor and, often, premature death. José Saramago’s Raised From the Ground, originally published in 1980 and now available in English, is an ode to the majesty of the land and the workers who poured their sweat and blood into it. Saramago follows four generations of the Mau-Tempo family through the tumult of 20th-century Portugal and the rise of the communist movement, chronicled through Joao Mau-Tempo’s gradual entrance into activism to his son Antonio’s passionate embrace of the cause. He brings this history to life using many devices: telling a gruesome tale of torture and death from the eyes of an ant, dispatching fireflies as escorts and guides for weary workers, and introducing us to Portugal’s Robin Hood, who steals pigs from the rich to sell to the poor at a reasonable price. It is a beautifully written epic, but Saramago’s single-minded focus on politics comes at the expense of building a deeper connection to the Mau-Tempo family; they anchor the story and help guide us through the decades, but fall short of becoming emotionally alive characters. Despite this, Raised From the Ground presents a breathtaking view of this momentous period in Portugal’s history that was so personal to Saramago and sets the tone for his distinctive style of writing.

—Allison McNearney

Always LookingBy John Updike

A final collection of essays on art by the prince of American letters, who began his career with aspirations as a cartoonist.

“My transition from wanting to be a cartoonist to wanting to be a writer may have come about through that friendly opposition, that even-handed pairing, of pictures and words,” John Updike writes in the preface of Always Looking, a posthumous companion to his other celebrated collections of essays about art, Just Looking (1989) and Still Looking (2005). Before he became a prolific novelist, Updike aspired to a career in cartooning and studied at the Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art at Oxford University. It’s no surprise, then, that reading his accounts of exhibitions is like seeing them in person with an informal (but extremely well-informed) curator—one with a novelist’s gift for narration and psychological insight. Always Looking, his third and last collection, includes reviews of museum exhibitions that he wrote for The New York Review of Books and The New Republic. He decodes Max Beckmann’s cryptic triptych Departure, which has inspired infinite interpretations. He explores works by Monet, Klimt, Degas, Miró, and Magritte, among others, and the movements of impressionism, pop art, minimalism, and surrealism. (He reflects on America’s problem with surrealism: “American art in general ... takes to surreal exaggerations and metaphors; but its Puritan work ethic has little use for the playful self-indulgence behind Parisian Surrealism.”) It’s worth mentioning that his descriptions of the experience of seeing exhibitions are no less remarkable than his analyses of the art on display. He captures the comic atmosphere at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s exhibition of paintings by Gilbert Stuart: “Fourteen portraits of the Father of Our Country in one grand custard-yellow room—a herd? a flock? a bevy? of George Washingtons! Such a concentration has its comedy as well as a surreal grandeur. The image is so familiar as to leave an art reviewer wordless. Even the chirping children were momentarily hushed.” Always Looking showcases a man who was a magician with words and—like all of his work—allows us to see the world through the eyes of a savant.

—Lizzie Crocker

The Last of the DuchessBy Caroline Blackwood

Not a biography of Wallis Simpson, but the story of Blackwood’s dogged attempt to get past the duchess’s cunning “necrophiliac” lawyer.

Caroline Blackwood belonged to the age of aristocracy, heroic talents, and monstrous personalities—it helped that she was married to two of the most talented and monstrous of the bunch, the painter Lucian Freud and the poet Robert Lowell. In other words, she belonged to the age of Wallis Simpson, the Duchess of Windsor, whom King Edward VIII married, in scandal, after his abdication. Simpson did a lot to bring the English monarchy crashing to earth, but really the historical change was inexorable. Blackwood is critical of Simpson’s extravagant lifestyle—she and the duke traveled war-torn Europe with more than 200 suitcases. But, being herself one of “the last of,” Blackwood set out to find out what had happened to the aging duchess and ends up being somewhat sympathetic to her fate, for she discovered that Simpson’s French lawyer, Suzanne Blum, was lying to her about her condition and restricted any visitors apart from her doctor and nurses. In Blum, Blackwood had found her ultimate villain, so much so that as a journalistic account it probably can’t be trusted entirely, since there are too many unsupported rumors and speculations and the book was not published until after Blum’s death, in 1995. (Blackwood died the next year.) But the writing is funny and light in a way that doesn’t exist anymore, like a Fred Astaire tap dance. Reissued with a new introduction by James Fox, Blackwood’s book is not a biography of Simpson—she never got to see the duchess—but an examination of how the rich and famous so often “at the end find themselves at the mercy of those in their employ” and succumb to the tragedy of the twilight of the gods—a tragedy that Blackwood herself was determined to avoid.

The GateBy Natsume Sōseki

Pico Iyer provides an illuminating essay on what might be the frontrunner for Japan’s national novel by its undisputed master.

Pico Iyer, in his introduction to this new NYRB Classics edition, points out that nothing much happens in this midcareer novel by Japan’s greatest modern novelist—that Japanese literature is often precisely about nothing much happening. Instead, Sōseki depicts seemingly unimportant conversations and gestures between a married couple, Sōsuke and Oyone, who married without their families’ blessings and whose gentle tug-of-war betrays the continued consequences of such an act. They struggle to make a living in Tokyo, but when Sōsuke’s younger brother needs money for his education, the new load bears heavy on the couple, and Sōsuke goes to a Zen monastery to meditate and find answers. Of course, a deliberate quest for answers usually yields none, at least not to the obvious question at hand. So it is that The Gate doesn’t look like much ostensibly, like a Yasujirō Ozu film. But as an allegory it is a quiet masterpiece in a country known for its quiet soul. Sōseki said it was his favorite novel, and it is a symbol of Japan by its greatest master.

I Told You So By Gore Vidal, Jon Wiener (editor)

Vidal glows when he talks about politics—that much is evident in these four interviews about his favorite subject.

Gore Vidal died in July, leaving us many memorable quips to admire. But most mourners would also just as willingly ignore his political views, which tended toward the extreme and provocative, including believing that the Bush administration was “out to lunch” and let 9/11 happen and that Roosevelt provoked the Japanese to attack Pearl Harbor in order to enter the war. But this slim volume, which collects four interviews on politics that Vidal conducted with historian and The Nation journalist Jon Wiener in 1988, 2000, 2006, and 2007, shows us that you can’t have Vidal’s wit without his politics. He admired his grandfather, the populist U.S. Sen. Thomas Gore. He said his only beef with his distant cousin Al Gore was that he didn’t fight hard enough in the 2000 election. He liked Hillary Clinton, he said, and anyone who can get rid of “this Bush gang.” He was most proud of his political and historical novels in his Narratives of Empire series, which included Burr, Lincoln, Empire, Hollywood, and The Golden Age. Vidal grew up with politics in his blood and was his most free and uninhibited while talking about that rough world.