If the latest Washington gridlock rankles you, turn your eyes to the structural flaw in American elections that perpetuates these stalemates and that will plague us for another decade, unless we fix it.

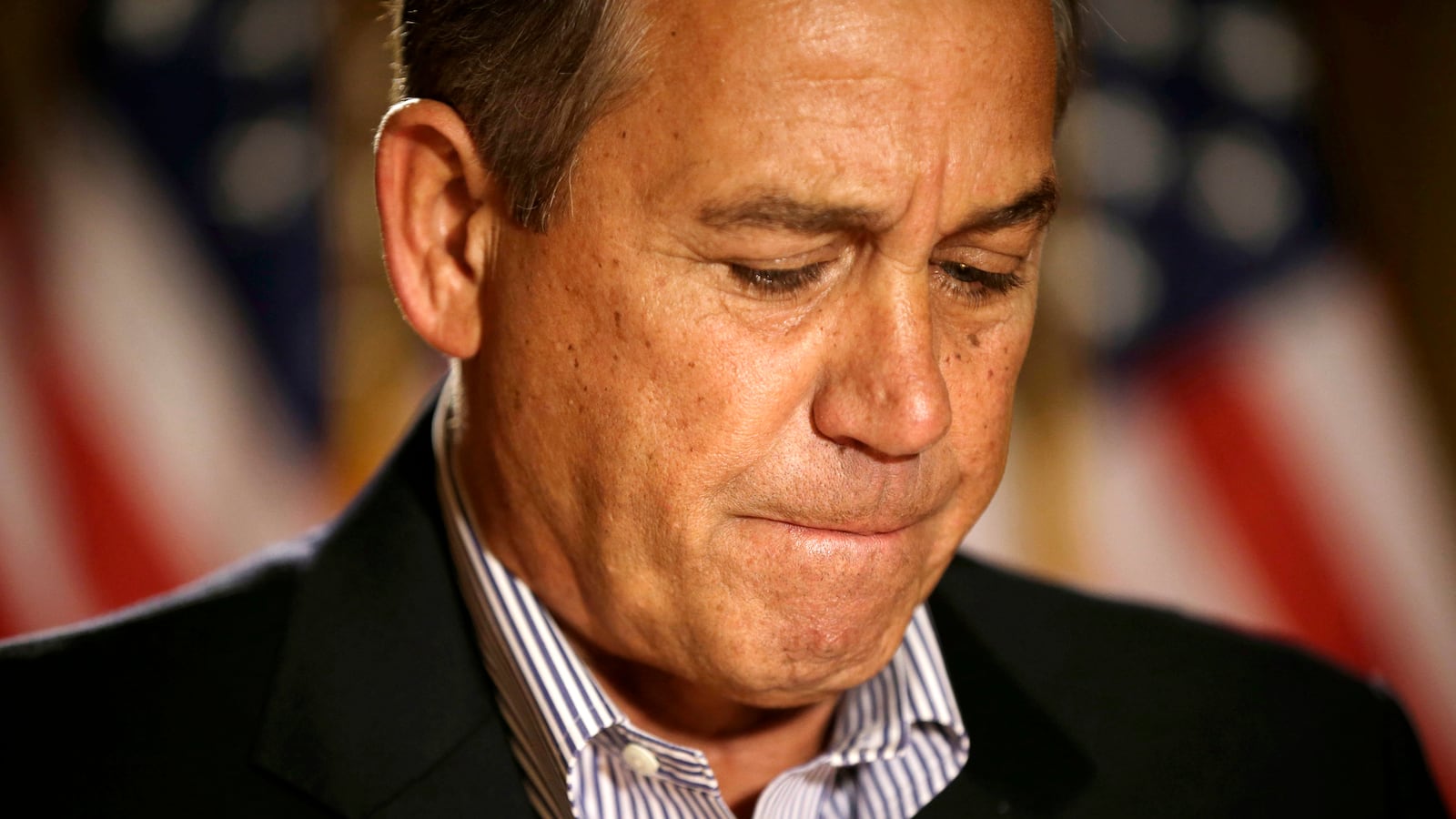

On the surface, it looks as though the American electorate deliberately split power between Democrats and Republicans and created gridlock. House Speaker John Boehner’s rejection of President Obama’s bid to raise income tax rates on the wealthy rests on the continuing Republican majority in the House and the claim that House Republicans won a mandate from American voters in November to keep all the current tax rates in place.

But that’s false. Republicans did not win an electoral mandate. In fact, they lost the popular vote for the House of Representatives. More Americans voted this year for Democratic House candidates than for Republicans and yet the GOP wound up with the House majority. That happened once before—in 1996.

By the Associated Press unofficial vote tally, Democratic candidates for the House won a million more votes than Republicans—56,056,564 to 55,028,230—and yet the Republicans got a House majority, 234 to 201.

Most of us know that what mostly stacks the deck is the gerrymandering of congressional districts. After the 2010 Census and the 2010 elections, Republicans controlled the most state legislatures and governors’ mansions and that gave them the power to draw district lines in their own favor.

As we learned in high school history, Gov. Eldridge Gerry of Massachusetts pioneered the practice of manipulating the boundaries of congressional districts for partisan advantage in 1812. Since then we’ve passively ignored how this partisan tactic distorts the way Congress writes our laws. But in the past few decades, gerrymandering has become so egregious that it undermines the credibility of House elections.

Right now, this stacked election deck threatens to have pernicious consequences for the winners and losers in Washington’s fiscal civil war. Gerrymandering also makes reaching political compromise much harder, because it makes it more difficult for moderates to win elections, and moderates have historically often been the key to congressional compromise.

Even in the current lame-duck Congress, the dynamics of the fiscal-cliff battle would be different if the popular vote were more accurately reflected in the partisan lineup in the next House: The Republican majority starting in January would be smaller—closer to parity with the Democrats. That prospect would change the balance of power in the current Congress.

“It would obviously generate more pressure on Speaker Boehner for compromise on big issues,” asserts Rep. Chris Van Hollen, the ranking Democrat on the House Budget Committee. “It would have a moderating influence in the House. It would make it easier to strike a grand bargain.”

Consider the five states that epitomize the gerrymandering distortion—Pennsylvania, Michigan, North Carolina, Wisconsin, and Arizona.

In Pennsylvania, Democratic House candidates outpolled Republicans by 2.7 million to 2.6 million votes, but the Republicans got 13 House seats to just five for Democrats. In Michigan, Democrats outpolled Republicans by 2.3 million to 2.1 million, yet Republicans won nine seats to five for Democrats. In North Carolina, Democrats won 2.2 million popular votes to 2.1 million for Republicans, but the Republicans have won nine seats to three for Democrats, and one race is deadlocked in a recount. In Wisconsin, Democrats had an edge of 43,000 votes, but Republicans won a five-to-four seat advantage. In these four states, a more accurate reflection of the popular-vote percentages would have given the Democrats 11 more seats and Republicans 11 fewer—a big swing.

One state cut the other way. In Arizona, Republicans won more popular votes than Democrats in House races, but Democrats got five seats, Republicans four.

What’s more, the partisan manipulation of congressional districts garbles more than the numbers. It sharpens the partisan divide in Congress. Both parties try to create safe districts and within those highly partisan lines, moderates tend to lose out and extremists tend to win. Both parties become more polarized. Without gerrymandering, red states would be less red, and blue states would be less blue. The middle would have more chance to re-emerge.

Take Massachusetts and Connecticut, where Democrats employ gerrymandering to knock off moderate Republicans, such as former Representative Chris Shays of Connecticut. In fact, last month, Republicans won about 30 percent of the vote in those two states, but Democrats won all 14 House seats. Republicans got none. In Maryland, too, Republicans won 38 percent of the vote but got far less than their share of seats—only one out of eight.

The tables were turned in Texas, where gerrymandering gave Republicans six more seats than justified by their popular-vote percentage. In many less-populous red states, from Alabama and Virginia to Indiana and Oklahoma, Republicans gained extra seats through gerrymandering. Coupled with the upside-down results in Michigan, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, the GOP piled up enough extra seats to overturn their nationwide loss in the popular vote.

Political scientists like Tom Mann of the Brookings Institution caution that it is impossible to assume that popular-vote percentages based on 56 million Democratic voters vs. 55 million Republican voters would translate automatically into a Democratic House majority in January, even if district lines were drawn by some impartial Solomon.

This is largely because of where people live, asserts Mann. “Democrats tend to cluster in big cities and so it’s hard to draw districts that evenly match popular votes,” he observes. “Republicans are more efficiently distributed (for voting results) than Democrats. They’re more spread out, and so they get a natural advantage from that.”

But reformers in nonpartisan movements like Third Way contend that congressional elections could be made much fairer if the job of drawing district boundaries were taken out of the hands of the two political parties and turned over to the courts.

They point to the experience of California, where twice since the 1970s lawsuits have forced redistricting of state legislative districts into the courts and where retired federal judges drew the district lines. Each time, the parties wound up with less of a political lock on districts and for several years, California had more competitive elections that reflected the the periodic swings of public opinion. Voters had more sway.

With Congress now at its nadir in public esteem, critics argue that it is time to restore an honest count in congressional elections by removing the stain of gerrymandering and putting courts in charge of restricting nationwide. In terms of electoral fairness, argues former conservative Oklahoma Republican Congressman Mickey Edwards, “political parties have turned out to be a disaster.”