Fears of white supremacists infiltrating the U.S. military date back at least decades. In the 1970s, a chapter of the Ku Klux Klan was discovered operating at California’s Camp Pendleton. It was not until 1986 that then Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger issued a directive requiring everyone in the military to “reject participation in white supremacy, neo-Nazi, and other such groups which espouse or attempt to create overt discrimination.” Recruiters were asked to screen potential recruits for incriminating tattoos and associations with potentially troubling groups. Yet as recruiting levels during the first years of the Iraq War continually failed to meet targets, incentives to look the other way were huge.

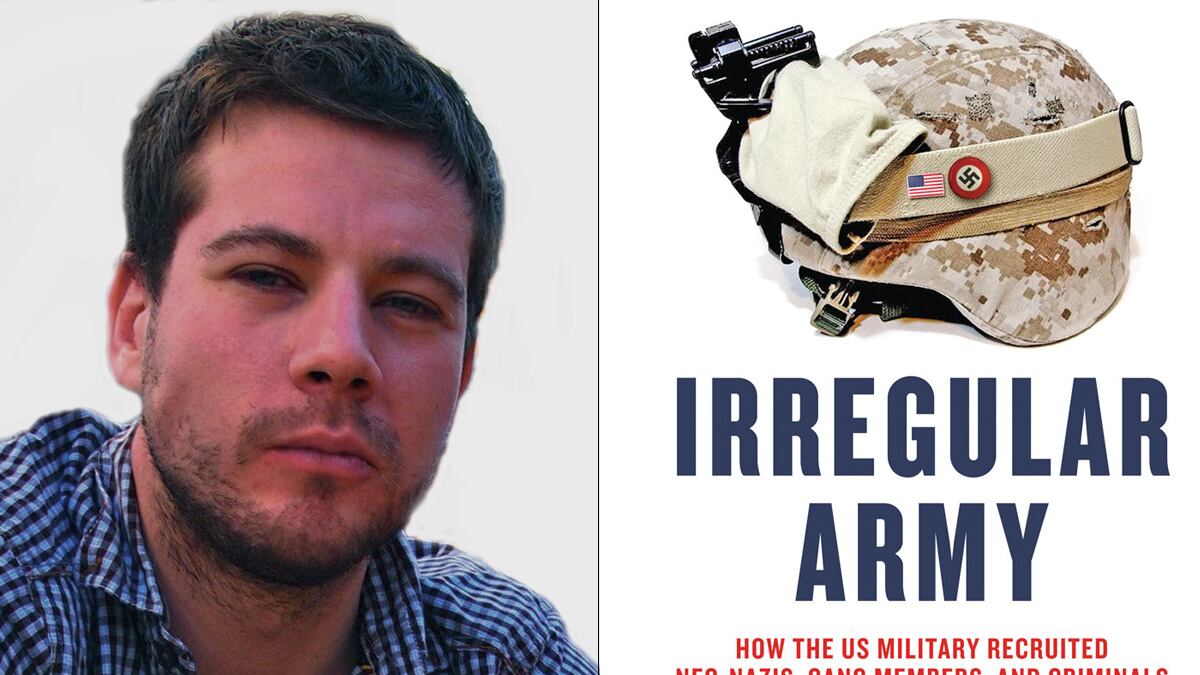

Matt Kennard’s Irregular Army: How the US Military Recruited Neo-Nazis, Gang Members, and Criminals to Fight the War on Terror is an angry account of how the Bush administration’s handling of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have necessarily reshaped the essential character of the armed forces—very often for the worse—by imposing operationally untenable political ideals on them.

Irregular Army begins by focusing on the prevalence of white supremacists and former gang members, groups that have had an increasingly easy time slipping through the military application process. “I get into fights myself twice a month because I’m a Nazi … I’m completely open about it,” one subject admitted to Kennard. Forrest Fogarty served in Iraq as a military police officer in 2004 and 2005, and had previously been associated with the National Alliance, the largest neo-Nazi organization in the country founded by The Turner Diaries author William Pierce. Fogarty is also the lead singer in the neo-Nazi hardcore band Attack, whose album Survival featured a photo of Fogarty in uniform and on duty in Iraq.

Many white-supremacist groups informally encourage people to enlist, not necessarily because of love for the government, but in order to gain weapons and combat training for the inevitable racial holy war, or RaHoWa. After the Trayvon Martin killing in Florida, a heavily armed group of National Socialist Movement members patrolled the streets anticipating retaliatory attacks on white people. The group has also sent volunteers with camouflage uniforms and assault rifles to patrol the U.S.-Mexico border. In a 2009 report to the Department of Homeland Security, analyst Daryl Johnson focused on these groups, writing that the “greatest fear is that domestic extremists … [carry] out a mass-casualty attack.”

Kennard cites a number of U.S. Army Criminal Investigation Command cases where neo-Nazi accusations were barely taken seriously. One soldier at Fort Hood was found to be posting on a prominent neo-Nazi message board, but no further action was taken because the investigator couldn’t find him for an interview. Another investigation in San Antonio found that a soldier had provided an Improvised Munitions Handbook to a leader in the supremacist group the Celtic Knights, which planned to attack five different methamphetamine labs around the city. The suspect was interviewed only once, and after the group failed to get explosives, the investigation was dropped in 2006. When Fogarty enlisted, his girlfriend at the time sent pictures of him at neo-Nazi rallies to his superiors. Fogarty was called before a committee and offered only one defense: his girlfriend was a “spiteful bitch.” The committee let him serve.

Discharge for misconduct numbers have fallen dramatically, from 2,560 in 1998 to 1,435 in 2006. Denials of reenlistment almost completely disappeared, dropping from 4,000 in 1994 to only 81 in 2006. These lax standards also made the military a more welcoming place for people in street gangs, like the Bloods, Crips, Latin Kings, and others. One of Kennard’s sources, Army Reserve Sgt. Jeffrey Stoleson, estimated street-gang members to make up as much as 10 percent of all soldiers. Stoleson served two tours in Kuwait and Iraq and reported gang members at every level, many of whom bragged about what they would do with their newfound military know-how. Stoleson reported what he saw to superiors, complete with large photo dossiers of gang graffiti tagged around military bases in Iraq, but was immediately labeled a snitch.

Military-trained gang members were especially in demand along the Mexican border. One 2007 report found 40 Folk Nation gang members stationed at Ft. Bliss who had been involved in drug distribution, robberies, assaults, weapons offenses, and even a homicide. The connection between organized crime and military experience have led to several domestic blowouts, and in many cases city governments have had to seek out either the military or National Guard assistance to fight against gang violence. All the while the military continued to hand out waivers to new recruits in record numbers. By 2007, one in every five military recruit received a waiver for something that would have otherwise flagged them for further review or rejection.

Kennard describes how this lowering of recruiting standards exacerbated many of the military’s worst institutional flaws. For instance, there are only 500 mental health professionals working in an Army of more than 1 million. Unsurprisingly, post-traumatic stress disorder rates for American soldiers are close to 30 percent, but for British soldiers who’ve fought in Iraq that number is only 3 to 4 percent. For German soldiers who fought in Afghanistan, the PTSD rate is 2 percent.

A woman serving in the Army is more likely to be raped by a fellow soldier than killed by enemy fire, and yet only 8 percent of all rape allegations in the military are ever prosecuted. Among the waivers issued to soldiers in 2006, 30 percent were for medical reasons, often related to being overweight. Yet, in the Green Zone, fast food companies like Pizza Hut and Burger King were allowed to compete with mess halls to feed soldiers. Likewise, there are more than 50,000 narcotic prescriptions filled for soldiers every month, including the amphetamine Dexedrine, which is used to help soldiers stay alert through long shifts.

Irregular Army might have made an even stronger case by widening its view of history. The composition of the American military and its connection to criminal groups is a long and complicated one, from the collaboration with Lucky Luciano to protect the New York waterfront during World War II to the rise of the Pinkertons and their role in attacking 19th-century unionizers.

Yet, Irregular Army makes a narrow but strong case that nothing good lies in the future so long as the American government continues to dissolve its standards of human decency to keep the pipeline filled with new soldiers. “What the War on Terror has shown us is that the Pentagon is prepared to dispense with both its regulations and its moral compass when faced with the need to stock future wars with soldiers,” Kennard writes. When the Rumsfeld-led Pentagon insisted on invading Iraq with 130,000 troops despite General Tommy Franks’s “Generated Start” plan that had asked for 275,000 soldiers, a titanic set of operational problems were set in motion. With as many as two-thirds of all Americans believing the war was worth fighting, and only one in three men in America met the physical, mental, and educational requirements that were the standard pre-9/11, the difficulty of recruiting new soldiers became a dire problem. The last 10 years have seen a prolonged and widespread lowering of standards that has left us with an army that is less fit, less well cared for, and less reliable than it had been before the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

More than a decade after the decision to invade Afghanistan, and more than nine years after the debate over invading Iraq ended, the dramatic reams of rhetoric have evaporated and left in their wake an operational mess. At some point the terror we are sending American military to fight will become indistinguishable from the terror it is creating, if only because we have begun to lose control over what we are doing and why.