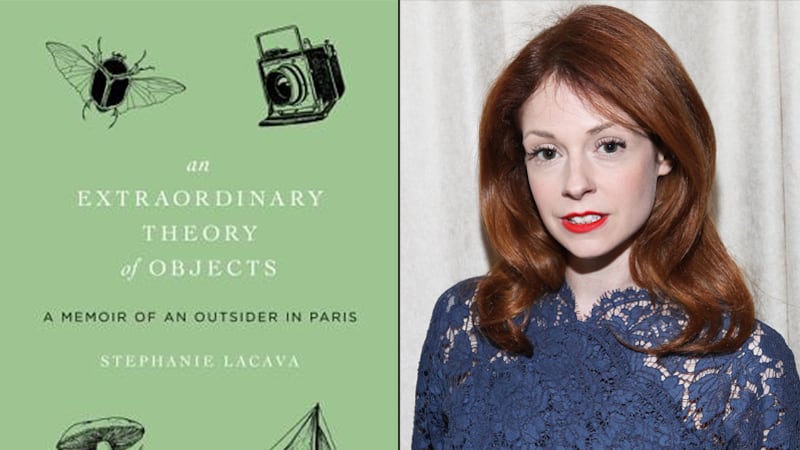

“I was always strange,” begins Stephanie LaCava’s memoir An Extraordinary Theory of Objects. It is clear from this that LaCava has always been an object of interest to herself, as well as to others. This was exacerbated when, at age 12, her father’s job caused her family to move to the posh western suburbs of Paris. In France, this outside interest wasn’t always kindly: the locals viewed her with disdain; the kindlier ones didn’t know what to make of her: “It doesn’t make sense: American girl, French accent.”

LaCava describes the difficult time she had fitting into her new environment through a series of curiously compelling objects, whose histories she details in footnotes below line drawings of the objects. A born collector, LaCava has a mania for the singular and unusual, and as a lonely, friendless teenager in France she cherished relics like a carved whale’s tooth, a ratty cardigan, a skeleton key, a beetle collection. Building this collection gives her a sense of control in a world where her parents were making major life decisions on her behalf. For LaCava these things are comfortable in their solidity, and the stories they tell give her fanciful distractions from her teenage angst. Although she didn’t want to move there, Paris turned out to be a great place for object collecting, and LaCava’s eccentric and indulgent father schooled her in the finer points of trinket-hunting at the flea markets.

But Paris can also be a cold, unfriendly place to those who don’t fit in. As is often the case for Americans in Europe, LaCava is disillusioned by her encounter with the Old World. When she first arrived in France, she writes, “I trusted everyone and everything, but in particular the things I could hold.” In time, however, the combination of her sensitivity and compulsiveness, the abusiveness of the other girls at her international school, and her constant anxieties about her father’s safety during the 1995 Paris Métro bombings produce a nervous breakdown in a forest in Burgundy.

Although on the surface An Extraordinary Theory of Objects is the charming illustrated story of a young girl’s intellectual obsessions with the objects and women who inspire her—Lee Miller, Jean Seberg, and Nancy Cunard are among her heroes, because they too felt the threat of depression along the edges of their lives—there is a darker, more serious undercurrent to this book, which demonstrates the violence young women can commit against their bodies when they are made to feel inferior.

LaCava tells us at the end that her problems turned out to be “chemical,” but her story indicates her difficulty transitioning not only from the U.S. to France but from childhood to adulthood. The psychoanalyst Anna Freud—whose father was a great collector of the weird and wonderful—famously studied the role of talismans in psychological development, noting that among children, objects functioned as a healthy, normal part of development, but prolonged attachment to these objects into adolescence could prove to be obstacles to happiness. LaCava’s talismans begin as protective elements against an unpredictable and frequently hostile environment, but they cannot help her fit in. If anything, they affirm her difference.

LaCava is a writer with a rich and quirky sensibility; her language is as ordinary yet as strange as the objects she seizes on. Her sentences are straightforward, dead-pan, and wonderfully weird: picking a mushroom from the forest floor, LaCava notes: “The classic storybook mushroom with its red cap and white spots is the drug of choice among Siberian-dwelling reindeer.” Each object receives a thoughtful drawing by Matthew Nelson as well as a footnote in which LaCava describes the object’s history, enrapturing the reader with her idiosyncratic stories and her flair for connecting unlikely subjects. An entry on the violet, for example, begins with violet-flavored candies, culminates with Napoleon placing flowers on Josephine’s grave, and concludes with perfume-making in Grasse using violets gathered between 5 and 7 o’clock in the evening.

Given that LaCava is a fashion writer, one wishes she had probed a little more deeply into the social value of objects, or made more explicit the connections between her lifetime of collecting and her success in the fashion world. A footnote toward the end of the book gives a short, wonderful history of human adornment, but the discussion remains didactic.

The “theory” of the title is summed up in the introduction: “As humans we crave beauty and we attempt to hold on to this experience through physical evidence.” That craving, LaCava realizes by the end of her story, set in 2009-10, doubles as a kind of control. “You’re OK,” her boyfriend tells her on a trip to Paris when she wants to feverishly comb the markets and he wants to relax and enjoy the city. “Don’t think so much. You’re missing everything.” This is, then, a memoir not only of holding onto things, but of letting them go, too.