“I think the essence of love is being there for the other person, no matter what that involves,” says Michael Haneke.

An exploration of love is one of the last things you’d expect from the oft-prickly Austrian auteur, whose sinister oeuvre, includes—but is not limited to—the sad travails of a sadomasochistic piano professor (The Piano Teacher), a dark French-Algerian race-relations allegory (Caché), and a stark portrait of the origins of fanaticism (The White Ribbon). Haneke, however, is in a decidedly genial mood on an overcast fall day in midtown Manhattan—and with good reason.

His latest film, Amour, won the Palme d’Or at Cannes, is the Austrian submission for the Best Foreign Film Oscar (despite being in French), and recently was named not just the best foreign film of the year but the best film of the year by the Los Angeles Film Critics Association as well as A.O Scott of The New York Times. It has a great chance to be the first foreign-language film to be nominated for the Best Picture Oscar since 2006’s Letters From Iwo Jima, and the first entirely foreign production to achieve that milestone since 2000’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon.

ADVERTISEMENT

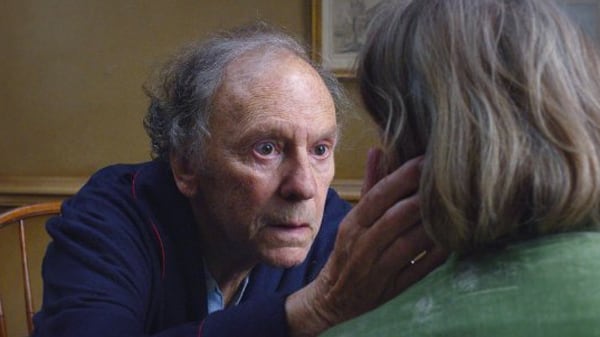

Amour, like most of Haneke’s films, centers on a bourgeois couple—Georges (Jean-Louis Trintignant) and Anne (Emmanuelle Riva). They are a pair of retired music instructors in their 80s living in a beautiful apartment in Paris. They are very much in love. One morning over breakfast, Anne stops talking mid-sentence and goes silent. Georges’s attempts to get her attention prove futile, for she is catatonic. Moments later, she snaps out of it and has no recollection of the incident. Later, Anne has surgery on a blocked carotid artery, but the operation is botched, resulting in wheelchair confinement and partial paralysis. Anne makes Georges promise to never return her to the hospital, and he abides by the agreement, despite their daughter’s (Isabelle Huppert) protestations. Anne eventually suffers another stroke and Georges, ever the loving husband, becomes her sole nurse and caretaker.

“The starting point of the story is that there was an aunt of mine who was suffering, and it was very unpleasant for me to have to witness that,” said Haneke. “But the story that I tell onscreen has little to do with the story that I experienced myself.”

In order to be as precise—and respectful—as possible, the director spoke with friends who have relatives that experienced similar circumstances, consulted with doctors, and spent time in hospitals observing the speech-therapy sessions of stroke victims. After the copious research, Haneke wrote his screenplay with French actor Jean-Louis Trintignant in mind. Trintignant hadn’t shot a film in 14 years, but agreed to the role due to, according to the actor, Haneke’s “complete mastery of the cinematic discipline.”

Then it came time to cast the role of Anne.

“As a young boy, I had seen Hiroshima Mon Amour but hadn’t heard much from [Emmanuelle Riva] since,” said Haneke. “When I was casting the role, I met with many actresses in her age group and not only was she by far the best actress, but she formed the most believable couple with Jean-Louis.”

The film was shot in seven weeks sans rehearsals, since Hanekes says he’s “not a fan of long, preparatory discussions about the script” and believes onscreen chemistry hinges on “casting the right actors, getting on set, and working through the mistakes.”

And the two actors’ esprit de corps is extraordinary. As Anne deteriorates, Georges is there by her side every step of the way, injecting love and compassion into every noble assist, from helping her relieve herself to calming her frequent night terrors. It’s as seemingly genuine a depiction of love, humanity, and empathy as has ever been captured on film.

“I don’t see the film as romantic,” said Haneke. “It’s true that the film represents love, so it’s tenderer than many of my other films, which represent violence. But if I shot a commonplace love story with young actors, I’d never dare to call it love. It depends on the context. In the context of this film, it’s about love.”

He adds, “I don’t think love is necessarily a relationship that has to last eternally; there are momentary desires as well. But it’s true that lust and love are very different in the same ways passion and love are very different, since love is a wider notion and can encompass many different aspects.”

The son of German actor/director Fritz Haneke and Austrian actress Beatrix von Degenschild, Haneke became a film critic and editor at the German TV station Südwestrundfunk, after a failed attempt at acting. He grew up admiring the works of Bresson, Tarkovsky, Hitchcock, and Cassavetes and, after directing several films for television, made his foray into feature films with 1989’s The Seventh Continent.

He’s grown to become one of the most celebrated voices in cinema, and is one of only eight filmmakers to be awarded multiple Palmes d’Or. His next production will be an opera—Mozart’s Così Fan Tutte, a more risqué love story about the age-old practice of “fiancée-swapping.” But our conversation eventually circled back to his initial profession. And, when asked about the current state of film criticism, the filmmaker took a long pause.

“If our film comes out and the reviews are uniformly negative, it’s unlikely that we’ll find an audience,” he says. “That’s not true for blockbusters, which play to the kind of people who don’t read reviews; they seem immune to reviews. But for author films, they rely on reviews to reach an audience. It’s also not just a matter of the review, but the reviewer as well. In general, I’d say 5 percent of reviewers are excellent, 15 percent are just fine, 10 percent are bearable, and the rest are complete idiots.”

He pauses again.

“Although that applies to every profession, including directors. It’s only really a problem when you’re talking about doctors.”