“Writing, at its best, is a lonely life,” Ernest Hemingway said in his 1954 Nobel Prize acceptance speech. “He grows in public stature as he sheds his loneliness and often his work deteriorates. For he does his work alone and if he is a good enough writer he must face eternity, or the lack of it, each day.” For full access to a genuine voice, Hemingway argues that a writer must depopulate his or her world, physically or metaphysically. (Though Hemingway seems to have depopulated his world of big words instead.) To write is to be completely and utterly alone during the course of the process—or at least pretend to be.

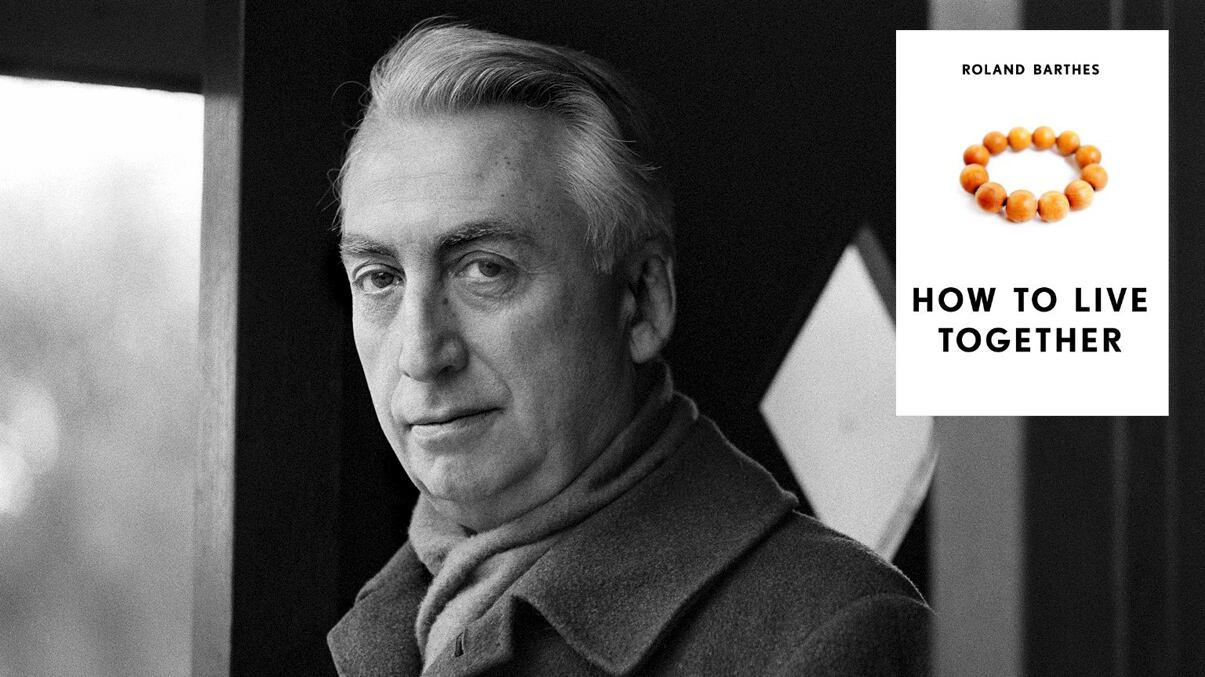

But what if you could be alone and together at the same time? In 1977, French literary theorist Roland Barthes gave a lecture course on precisely that, the notes of which have been translated by Kate Briggs and gathered into the book How To Live Together.

Central to Barthes’s argument is the idea of idiorrhythmy. It is a term most often associated with monks and which describes a method for people to live together but also apart——individual planets orbiting in a communal galaxy. In a monastery, the wall is a symbolic divide between the believer and the non-believer, between sacred and civilian space. Boundaries tell us who we are not as much as they tell us who we are. Houses are usually made of 90-degree angles, but rarely do we find them in nature. In the same way that square or rectangle frames separate a work of art from “reality,” our homes frame, define and separate us. Ninety-degree angles might be artificial, but they do allow homes to be organized efficiently into apartment complexes, neighborhoods and cities. Alone and together.

In August, The New York Times published a series of photographs by Carlo Bevilacqua of individuals who have separated themselves from society, usually for spiritual reasons—the subjects are mostly monks, hermits, and recluses. One image looks like a Dr. Seuss illustration, showing a house perched atop a looming rock formation. There’s something irresistibly attractive about these images—they show us the freedom we have over how we live our lives. Alone looks alluring in this age of hyperconnectivity and lack of privacy. “Today more than 50 percent of U.S. residents are single, nearly a third of all households have just one resident and five million adults younger than 35 live alone,” a New Yorker article published in April showed. Does living alone satisfy something in us that we’ve been denied, or are we simply incapable of living together?

Barthes himself did not live alone—he lived with his mother until the day she died. They shared a house in the country and a house in Paris that they bounced between, depending on the season. I wondered whether Barthes preferred it that way, so I spoke to the Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Richard Howard, who was Barthes’ translator and friend for 30 years. “I knew his mother. I met her at the airport and we had days together,” Howard told me. ”She was a wonderful woman, just remarkable. Roland lived with her. He had a room where he worked in the attic that he sometimes slept in. He lived a perfectly satisfactory, not very happy life in the room upstairs.”

To Barthes, idiorrhythmy is the ultimate domestic ideal. “Fantasmically speaking, there’s nothing contradictory about wanting to live alone and wanting to live together,” he wrote. But Barthes never had to accustom himself to the domestic idiosyncrasies and habits of a roommate, which many of us struggle to learn like a foreign language. That, perhaps, was the source of Barthes’s deep belief in idiorrhythny. “They had an understanding of each other and the life they wished to lead,” Howard said about Barthes and his mother. “I’ve never seen anything like it. He wanted to try to explain the possibility of lives being satisfactory that weren’t ordinary.”

In his lectures, Barthes used literary examples like Robinson Crusoe and The Magic Mountain to explore atypical living arrangements, but also to think about the way we define space. For example, nicknames are another way of establishing emotional enclosure: “The invention of new names: a way of breaking with everyone else and creating a supremely safe enclosure, a new integration; in short, a conversion.”

Despite being tied to his mother in ways most contemporary Americans would find slightly embarrassing, Barthes was not socially awkward; nor was he a recluse. He enjoyed his stature as a public figure in Paris. “He became a very famous man, and was known in the streets of Paris. When I would walk to lunch with him, people would point,” Howard said. “He wasn’t weird about being famous. He accepted it.”

As Howard pointed out, Barthes, who died in 1980, is now more popular than ever—“he’s hot stuff,” as he put it. Howard’s new translation (with Annette Lavers) of Barthes’s classic study of pop culture, Mythologies, came out earlier this year. How to Live Together is quite different, composed of notes that Barthes probably never meant to publish. It is more of an outline than a polished and complete project, consisting of fragments, questions and poetic gestures in a dialogue that rely on his students—or the reader—to participate in.

Even in this aspect Barthes did not validate the cliché of the solitary writer. “I loved translating him and he loved being translated,” Howard told me. In 1974, he wrote an essay on Barthes that pointed out that although “reading is still the principal thing we do by ourselves in culture,” we read alone in order to not feel so alone, to connect with the voice of another human being. Barthes himself wrote that Robinson Crusoe is “an epic tale of solitude [that] enjoys the mythic status of a novel conceived for the express purpose of enriching the experience of solitude: ‘the book you’d take to a desert island!’” That, also, is the best thing about Barthes—he enriches our experience of solitude by leaving us images like this: “Living together: perhaps simply a way of confronting the sadness of the night together. Being among strangers is inevitable, necessary even, except when night falls.”