I first heard about Ciudad Blanca, or the White City, in 2008 while reporting a magazine story about the drug trade in Honduras. People had been searching for the lost city at least since the conquistador Hernán Cortés wrote to the Spanish emperor in the 16th century about a wealthy and hidden place deep in the jungle. Over the years, explorers were driven by stories of gold, priceless artifacts, overgrown temples and “monkey gods.” “I always thought about going out there to find it,” an ex-military man who had spent time in Honduras told me. But, worried that he would never escape the jungle, he never tried.

Some nights, when my wife and 3-year-old daughter were asleep, I sat at my computer in the living room and mapped the Honduran jungle, shooting Google’s satellite camera downward, flying over the winding rivers and tightly packed trees that made up one of the largest rainforests in the world. I called archaeologists, prospectors, adventurers, and crackpot conspiracy theorists. My curiosity crossed into obsession when I encountered the story of Theodore Morde, an American spy who in 1940 claimed that he found the sacred place only to die mysteriously before disclosing the location.

“You want to do what?” asked Amy, when I first told her my plan.

“I want to find the White City,” I said.

She laughed, swallowed a sip of red wine and, though she’d heard many of my phone conversations with people about the city, searched my face for a sign that I might be joking.

“I feel old,” I said.

“Is that what this is about?”

“I’m just saying.”

“You’re not the only one.”

“I’d just like to do this.”

And so it was that about a year later, I found myself face to face with a man called Rana (Spanish for “frog”). A machete dangled off his leather belt, and he smoked a cigarette that I’d watched him roll. My three guides suspected that he, like others who strayed out here into the heart of Mosquitia, the jungle in southeastern Honduras, was a desperado, a convict, or some kind of trafficker. But all he wanted to talk about was the voices of the dead.

“There are people out there,” said Frog. “You can’t see them. You only hear them now. The ancient people.”

He pointed at his right ear, which glinted in the firelight with a silver stud earring, and his mouth extended into a sly smile, as if he possessed an old secret.

“They are dead, of course. These people.”

His cigarette smoke drifted around us in the humid jungle air. He shook his head. It was early July. There was nothing, and no one, around us for miles. And though it was the rainy season, the rain had stopped and the two-room thatch hut was alive with noise—chirping, tweeting, burping, groaning.

I squinted through a cutout in the hut: nothing but thick rainforest. The closest road was probably two days of walking and my satellite phone wasn’t working.

Frog looked to be in his late thirties, skinny and tough, in a red tank top emblazoned with dragons, ripped camouflage shorts, and a scuffed cowboy hat cocked forward on his head. We had encountered him and two of his friends, all of them armed with rifles or machetes, a couple of weeks into our search for the White City, on a desolate stretch of the Cuyamel River.

Frog said he was on the run, but didn’t say what he was running from or what he was doing now in this remote part of the country. We didn’t want to join him, but we had no choice; they had a boat, and we had no other way of getting down the river.

We had been trying to follow the trail of Theodore Morde, hoping that his journals, which few had ever seen, might lead us to the White City. I was itchy from the bugs, aching everywhere, blistery, and wet. My boots were shot. My back hurt. I stunk. I hadn’t slept in days, had run out of Valium the night before, and longed for my wife and daughter, whose 4th birthday I was about to miss.

"You’re a long way from home,” Frog said, as the rain returned.

I laughed, but he didn’t crack a smile.

"Are you lost?” he asked.

He looked me hard in the eye. He said it was easy to lose your way in the jungle. “Don’t follow the voices of the dead,” he warned. “That’s my advice for you.”

I said goodnight, retreated, and slumped into my hammock, the rain slapping the tarp over me. I looked out at the wet, impassable hell of the jungle and heard my wife’s voice over and over again from the day I left home. “What are you thinking? What are you really looking for? Why are you leaving?”

Morning was still hours away, but I couldn’t sleep.

***

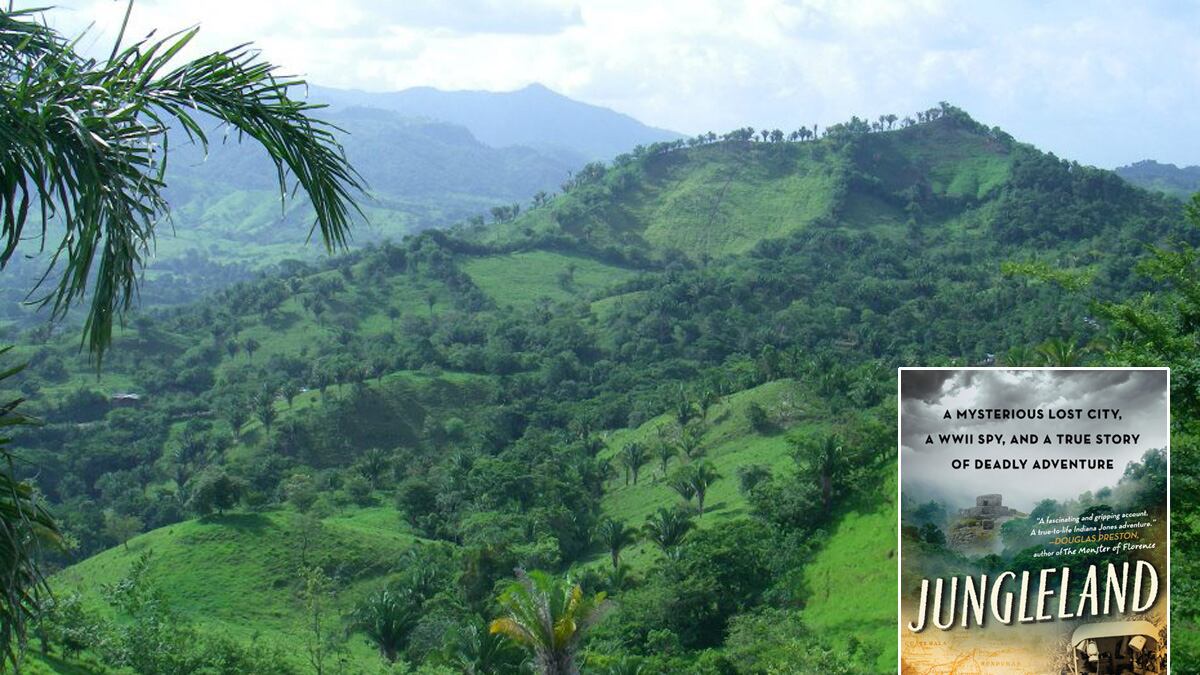

A week later—and many more miles of trekking over mountains, across valleys, and through swamps—we found the ruins. It was Aug. 1, about a month from the day I arrived in Honduras. Around us, the forest alternated with land that was burned and cut, where copper-red shapes of mahogany stumps stood out of islands of second-growth grass and vines.

Steadily, our gunman pushed forward, his mule high-stepping through brush. We saw the large mounds that some nearby villagers had mentioned the night before. Some as high as 10 feet and in groupings of twos and threes, they were larger than the mounds we’d spotted along the river. “They’re everywhere,” exclaimed Chris Begley, my guide and an American archaeologist. He was stunned. I couldn’t stop thinking about the entombed giants, and I had the feeling I was walking through a graveyard.

Chris paused in a stand of tall trees. “Look there,” he said, flicking his machete at the shaded ground. “It’s easy to miss.” He kicked away some vines, revealing disfigured cobblestones scattered about in what resembled a crude pathway. “It’s a road,” he said, excitedly.

“A road?” I repeated, imagining asphalt with yellow broken lines.

“Yeah, a road. It’s probably a thousand years old or more.”

He said that roads were built between neighboring cities and from city centers to the closest river, where people and goods were shipped in and out of the jungle. “You couldn’t move here without a road. Think of all that mud we walked through.”

Chris scrambled ahead, until he stopped again at an open expanse, where two large stone walls protruded from the grassy earth. Several feet tall, rounded off at the top, with creepers and weeds engorging them, the wall extended for many yards, like giant anacondas, before disappearing into the horizon.

“Do you see it?” Chris asked. He pointed across the upturned carpet of green wilderness. It was early afternoon. For the first time in days, there weren’t any dark clouds in the sky. But the rain would come. It always did.

“What?” I said.

He smiled. “The city,” he said.

“What city?” I didn’t see anything. Of course, I had been imagining great ruined white buildings, tall vine-strangled columns, the spooky statues of giant monkey kings that Morde had talked about.

Chris chuckled. “You’re standing on it,” he said. “It’s all over.”