Say what you want about Barack Obama: he learns from his mistakes. In the early debates of the 2007–08 primary campaign, his answers were often long and meandering. By the end he was outclassing Hillary Clinton night after night. In his first debate with Mitt Romney, he seemed focused, above all, on being polite. In the second and third he focused on winning every exchange.

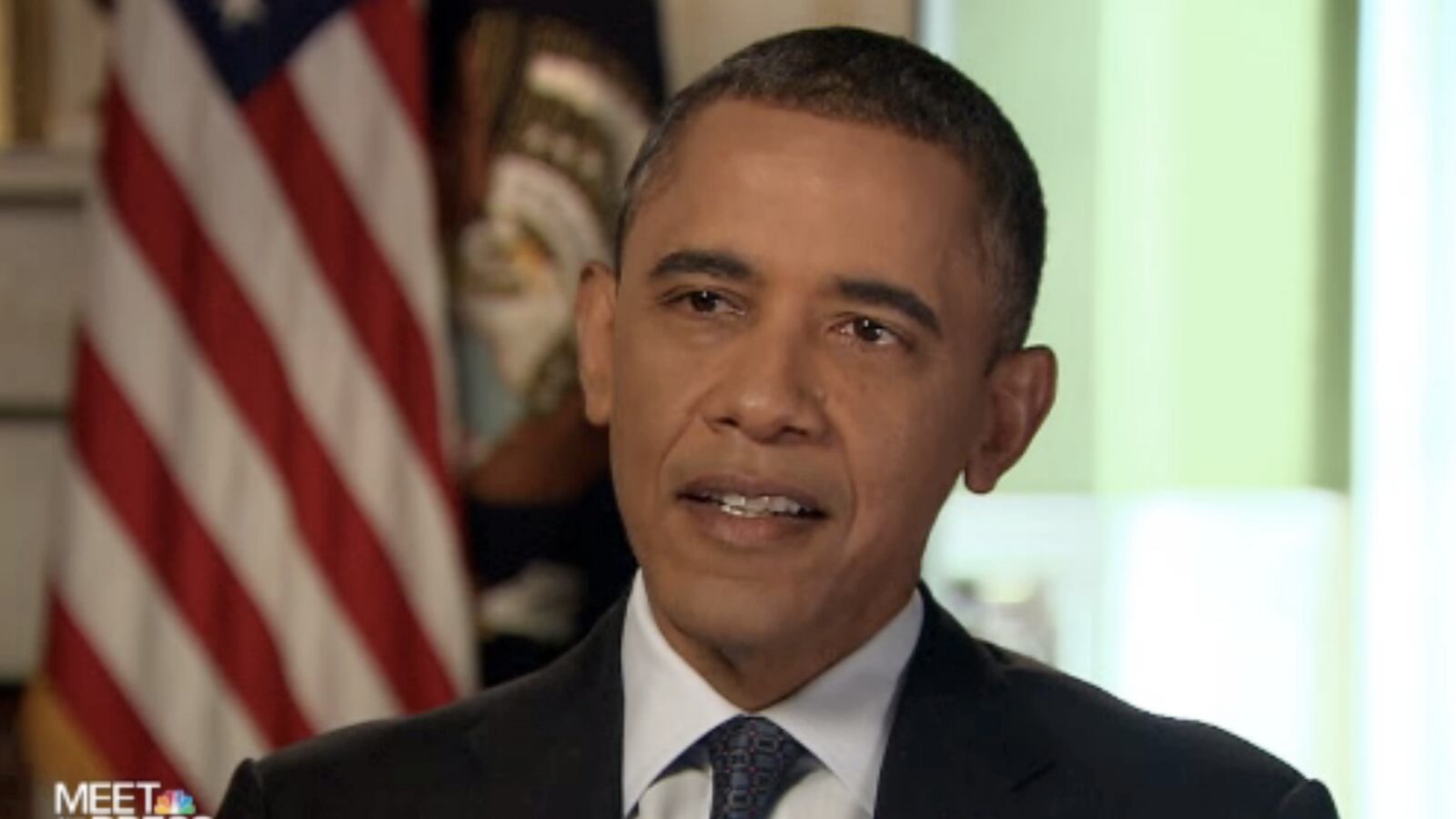

You can see the same improvement in Obama’s televised tussles with a different sort of political foe: David Gregory. On Sept. 20, 2009, in the midst of the battle for health-care reform, Obama sat down with the Meet the Press anchor and talked like a man who thought he was ushering in a post-ideological age. Instead of highlighting the differences between his health-care vision and the one championed by Washington Republicans, Obama blurred them. Instead of insisting that the 2008 campaign represented a public endorsement of his health-care agenda, he treated the campaign as a bout of unpleasantness best forgotten.

“I actually think that we’ve [Democrats and Republicans] agreed to about 80 percent” of the substance of a future health-care law, Obama told Gregory in his first answer of the interview. “The key is now just to narrow those differences.” But “those narrow differences can also, in some cases, be very big differences,” replied Gregory, virtually begging Obama to distinguish his vision from the GOP’s. But Obama refused, instead pointing proudly to his efforts to erase the very ideological distinctions he had spent the 2008 campaign outlining. “I’ve already made some pretty substantial changes—in terms of how I was approaching health care” as a candidate, Obama insisted. A few minutes later he cited his embrace of medical-malpractice reform as one of “a whole series of Republican ideas, ideas from my opponents during the campaign, that we have incorporated.” He ended his discussion of health care by pleading that “we’ve got to get past some of these ideological arguments to actually make something happen.”

How did all this post-ideological talk work out for the president? Not well. Washington Republicans, as it turned out, didn’t want to narrow differences on health care. To the contrary, they told Americans that the difference between their view and the president’s was the difference between freedom and tyranny. And because Obama never effectively framed the ideological debate, or even quite conceded that there was an ideological debate, he never rallied the public to his side.

How times have changed. In that first presidential interview with Gregory, Obama mentioned the word “Republican” twice in relation to health care. In his second, conducted yesterday, Obama punctuated his discussion of the looming “fiscal cliff” with seven references to the opposing party. And the emphasis was on opposing. Again and again, Obama stressed that on the budget, he and the Republicans have vastly different priorities, and that Americans chose between them last month.

“There is a basic fairness at stake in this whole thing that the American people understand and they listened to an entire year’s debate about it,” Obama told Gregory. “They made a clear decision about the—the approach they prefer ... They rejected the notion that the economy grows best from the top down.” Then in his next answer: “The way they’re [Congressional Republicans] behaving is that their only priority is making sure that tax breaks for the wealthiest Americans are protected. That seems to be their only overriding, unifying theme.” And soon after that: “What I ran on and what the American people elected me to do was put forward a balanced approach. To make sure that there’s shared sacrifice ... And it is very difficult for me to say to a senior citizen or a student or a mom with a disabled kid, ‘You’re going to have to do with less, but we’re not going to ask millionaires and billionaires to do more.’”

The analogies between Obama’s 2009 and 2012 interviews aren’t perfect. By September 2009, 10 months had elapsed since Obama’s election victory. Obama’s November 2012 win, by contrast, occurred less than three months ago. When Obama talked health care with Gregory in September 2009, the legislative process was far from playing itself out—there was no imminent deadline like the fiscal cliff—which may have inclined Obama to be more conciliatory.

But what the two interviews show unmistakably is that Obama has learned a hard but crucial lesson about contemporary American politics. In 2009 he was so enthralled with his ability to see the reasonableness in conservatives that he ended up patronizing them. Like many a technocratic liberal before him, he assumed that the real divide between left and right was over how government should intervene to solve national problems. Had Obama been dealing with the Republican Party of the Eisenhower or Nixon years, that assumption would have made sense. But that GOP died long ago. And in 2009, Obama didn’t sufficiently grasp the right’s core conviction that no matter how grave the problem, enhanced government intervention in the economy will make it worse because enhanced government intervention in the economy threatens freedom.

We don’t know how the current budget fight will resolve itself. But this much is already clear: Obama is treating it as an extension of the campaign he just won. That’s a very good thing, because although the GOP is today a deeply anti-government party, Americans are not in a particularly anti-government mood. And thus, as Obama showed John McCain and Mitt Romney, when a Democrat takes the GOP’s anti-government ideology seriously enough to forthrightly reject it, the American people usually do too.