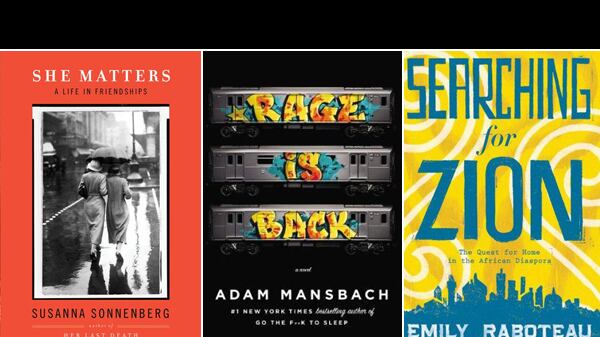

She Mattersby Susanna Sonnenberg

The author collects female friends like kitchenware, but engineers many interpersonal collapses.

One of the earliest stories in this searing volume recalls the weekend when author Susanna Sonnenberg’s mother visits her in college, meets her roommate Amy, and sets out to discover her secrets. She succeeds. After Amy confesses she and her boyfriend are having sex, Sonnenberg’s mother plans a birth-control expedition to Planned Parenthood with the girls. Amy is impressed—until her own parents appear a few hours later and Sonnenberg’s mother, “enjoying her dorm-room dominion, reassure[s] them that she had seen to their daughter’s contraceptives.” Amy moves out.

Sonnenberg collects female friends the way some people collect kitchenware; Amy is just one of the dozens of women who parade across the pages of this book. She Matters is both a remembrance of vital friendships as well as a deeply absorbing portrait of the author herself. The emotional hunger that propels her from one intimacy to another is laid bare as is the cocktail of character traits and quirks she seeks in a companion. Another thing gradually becomes evident: the pattern of her friendships’ life cycles. Most of Sonnenberg’s intense friendships end in misunderstanding and silence.

Sometimes, the culprit is simply life. Priorities shift, lines get crossed, circumstances and people change. But as Sonnenberg reveals more about her formative years, it becomes clear that she is the unwitting engineer of many of these interpersonal collapses. Many years after the Amy episode, watching the end of yet another close friendship, Sonnenberg writes, “I was worn out with forcing my ruin and longing upon woman after woman.” There are beautiful moments documented here—shared artistic journeys with Mary, the painter; deep bonds of respect and trust with C., the acquaintance of youth turned midlife friend; moments of confidence with Marlene, her father’s ex-girlfriend. But ultimately She Matters is a deeply affecting ode to the ones who got away.

Searching for Zionby Emily Raboteau

Her journey takes her to Israel, Jamaica, Ethiopia, Ghana, and even the American South. But home is where it’s at.

When writer Emily Raboteau reconnects with a childhood friend who has moved to Israel, she begins to feel a profound hankering for a spiritual homeland of her own. “As a consequence of growing up half white in a nation divided along racial lines, I had never felt at home in the United States,” she explains. “Now more than ever, I wanted to feel connected to a place, a people.”

And so, in plucky Eat, Pray, Love fashion, Raboteau sets off in search of Zion, travelling first to Israel, then Jamaica, Ethiopia, and Ghana, and finally touring the American South. (She rules out Sierra Leone and Liberia because “I knew too much about the civil wars that had devastated both countries to take either of them seriously as successful utopias.”)

“It’s such a ridiculous cliché,” she complains to a friend at one point. “The tragic mulatto whining about not belonging. I don’t want to be that person. That’s not who I am.” That said, this is ultimately the identity she assumes for the purposes of the book. Though she is a thoughtful tourist, curious about the culture and history of the places she visits and alive to experiences, Raboteau doesn’t entirely escape the pitfalls of banality. Her search for authenticity gets her strip-searched, high on pot, and into bar fights, among other things. But in the end? “To end any story, even one far simpler than this is a magic trick,” she writes. “The Promised Land,” of course, “is never arrived at.” What she finds instead is her own family, and a road stretching out, with promise and uncertainty, ahead of her.

The Great Agnosticby Susan Jacoby

The biography of the talented orator Robert Ingersoll, who championed secular ideas that American politics could not tolerate.

Early in life, Robert Ingersoll, talented orator and “self-made American achiever,” had ambitions to hold public office. But in the mid 19th century, religious faith was a requirement for prominence in American politics and Ingersoll was an avowed agnostic, so he gave up a promising career to serve as a champion of secular thought instead.

A public intellectual well ahead of his time, Ingersoll tirelessly promoted equal rights for men, women, immigrants, and people of color, and advocated for scientific inquiry. His rhetoric mixed humor and passion with anecdote, making him a popular speaker, even among those who weren’t certain they shared his beliefs. But despite the influence he wielded in his lifetime, Ingersoll today has been all but forgotten.

In this persuasive biography, Jacoby makes the case that Americans are dearly indebted to Ingersoll, and would be well-served to revisit his life and writings at a time when religious thought continues to be a divisive force in American civic life. Ingersoll dreamed of a future when “the altar and the thrones have mingled with the dust,” when “aristocracy of land” was no more “and all the gods are dead.” It would be a time when free thought solved medical and social problems, ending oppression and deprivation. It’s a lofty vision of secularism not as the mere absence of religion but as a call to action heavy with moral responsibilities of its own. In this important volume, Jacoby illuminates a mind worth celebrating and the story of a life well lived.

Rage Is Backby Adam Mansbach

A novel of bright and vulgar prose from the author of the faux children’s book ‘Go the F**k to Sleep.’

“I know more about nostalgia than anyone my age should,” Kilroy Dondi Vance says. Eighteen-year-old Dondi doesn’t have much to show for himself—he’s been kicked out of “Whoopty Whoo Ivy League We’s A Comin’ Academy” because of his “botanical enterprises,” but his unusual upbringing lends him a layer of sophistication. Dondi is the son of Billy Rage, one of New York’s graffiti legends, and grew up immersed in the lore of graffiti-as-a-way-of-life. He’s sure there’s more to city life than the usual hustle and grind. He just hasn’t figure out what yet.

For now Dondi spends his days wandering the city and getting high, much to the chagrin of his mother, Karen. His lack of direction might have something to do with the fact that his father has long been out of the picture, but Dondi is too self-aware to accept an explanation that simple. “I haven’t sidestepped all the other hood clichés just to blame my problems on skewed values in the home, or a dearth of positive male role models.”

Still, Billy’s sudden return, 16 years after he skipped town for Mexico, gives Dondi’s life new purpose. Billy and the other members of his old crew have some unfinished business with NYPD officer turned MTA chief Anastacio Bracken, the cop they blame for the death of one of their closest fellow “writers.” Bracken is now making a bid for New York City mayor. Can the old gang stop him? Dondi is willing to try. Rage Is Back is a funny, macho-but-vulnerable coming-of-age-story. It’s seeped in New York nostalgia and narrated in bright and vulgar prose that succeeds in hinting at no small quantity of swagger and soul. As Dondi says, “it’s not easy to talk from your heart and out your ass at the same time.” Delightfully, Rage Is Back manages to do both.

Truth in Advertisingby John Kenney

A single 40-year-old copywriter for Snuggies ads takes a chance on family and visits his dying estranged father.

When Finbar Dolan is alone, a small voice in his head taunts him. “You don’t think about words. You use them like you use paper towels,” it says. “Without thought or care.” Fin’s relationship with words, in fact, is bound up not with paper towels, but with diapers. He’s a copywriter at an ad agency whose biggest client is Snuggies. (Other products they represent include chocolate toffee Doodles and a major petroleum company responsible for a catastrophic oil spill.) He makes his way muddling through slogans about happy babies.

Advertising agencies are fine subjects for dark comedy, and Kenney has a knack for painting both the absurdities of the workplace as well as the existential weariness of just “getting by” in New York. However, this is really a book about family, not work. Despite warm flirtations with his coworker Phoebe, Fin’s personal life is largely in disarray. Never married and approaching 40, his last long-term relationship ended in a jilted bride and returned registry items. As he points out, he spends his days with diapers, yet he has never had to change one. Nor has he managed to forge any other kind of lasting kinship ties.

But when Fin learns that his estranged father is on his deathbed and none of his siblings plan to visit him, he decides to take a chance on family. It’s a decision that forces him to confront his past—and to work up the courage to finally search for “that elusive thing called happiness.” Truth in Advertising balances the droll with the hopeful and the glib with the heartfelt. “The annoying thing about life is that it screws up the production,” Fin muses. “It’s rarely neat and tidy. And yet sometimes it can surprise you.”