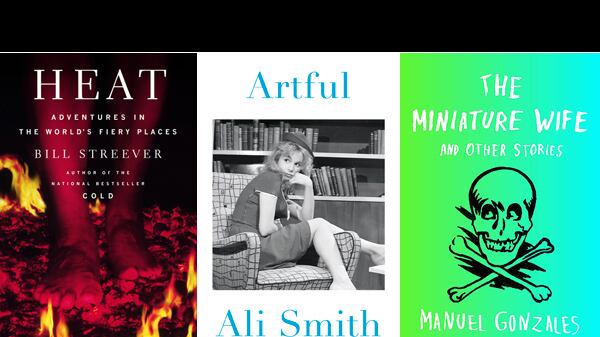

ArtfulBy Ali SmithWeaving between a ghost story and a meditation on literature, the British writer offers a master class in what creative writing is and does.

“The arts babblative and scribblative,” the poet Robert Southey once said. It’s not so much declarative as demonstrative, a sentence that displays its point: the arts are dumb, and they don’t need to “say” anything. Artful is Southey expanded. Through four chapters, Ali Smith muses “On time,” “On form,” “On edge,” and “On offer and on reflection,” alternating between commentary—usually in bullet points like “Putting the For in Form”—and a story where her lover, once a writer, comes back from the dead and haunts her house. The ghost does not understand words such as “two” and “time.” But when the narrator asks about the world on the other side, the ghost narrates a story of a bright-headed girl who hides on a boat and eats the crew’s bread and cheese with a look of total happiness. The ghost is also able to say words like “Trav a brose. Spoo yattacky. Clot so. Scoofy.” This specter is a wonderful reimagining of a muse, and the narrator’s love of Dickens (particularly Oliver Twist—Artful as in the Artful Dodger), Michelangelo, and poetry is reawakened. Smith offers a master class on writing by tip-toeing over the line between declarative and babblative, demonstrative and scribblative.

Revenge By Yoko Ogawa, Stephen Snyder (translator) Macabre stories whose darkness functions as a display of the wounded courage of women and men who manage to hang on to life.

A woman enters a bakery intending to buy two strawberry shortcakes, but there’s no one in the shop. Another customer enters—a short, plump woman, who turns out to be the bakery’s spice supplier—and offers to go behind the counter and do the serving herself. Yoko Ogawa’s early works focus almost solely on the cruelty of humanity, and accordingly she enjoys a reputation as Japan’s best teller of macabre tales. (She’s extraordinarily popular in France, too.) So you’d expect the bakery to be hiding something grotesque. The 11 stories in this collection are short, dark mysteries, and you might be familiar with E.M. Forster’s famous breakdown of the form: “The queen died, no one knew why, until it was discovered that it was through grief at the death of the king.” But Ogawa is such a master that she pushes the boundaries and suspends the mystery—the “no one knew why”—so much so that she never delivers the climax, or rather that she delivers it elsewhere. There’s nothing wrong with the bakery itself, and there’s no one in the store because the clerk is in the back room, crying on the telephone, though we never find out why. Turns out, the morbid secret belongs to the female narrator, who’s haunted by the chilling death of her son. Unlike her earlier stories, the macabre in Ogawa’s later works function to highlight humanity’s wounded courage. There’s great beauty in the woman’s sympathy for the crying clerk and how two strawberry shortcakes bring them closer together. The next story is about a girl who asks a boy she barely knows to go with her to meet her dad for the first time, but she never thanks him until many years later. Elsewhere, an old landlady, who gives massages to her tenants with extraordinarily cold, hard, bony hands, turns out to have killed her husband and buried the corpse—which is missing the hands. You never know “why,” only that humans are slaves to time, and we keep on with our lives so that someday we might understand.

HeatBy Bill StreeverA survey of high temperatures, from what extreme heat does to matter in a supercollider to what it’s like holding your hand over a candle flame.

Bill Streever has now covered the full spectrum. As he did with his previous book, Cold, Heat reminds us that our survival depends on maintaining ourselves within a very narrow range of temperature, but Streever has gone ahead and surveyed the extremes, up to 7 trillion degrees Fahrenheit, the highest temperature ever created in a laboratory, using supercolliders that recreate the heat just after the Big Bang. Heat changes things from one state to another, and to better understand the transformations of matter—or of the soul—Streever, following in the footsteps of the old-timer naturalists who came before him, goes on a personal journey to experience all types of heat. Just a six-degree change in our core temperature can give us heatstroke and kill us, and Streever tries to avoid that fate as he walks across Death Valley. He goes to the Kilauea shield volcano in search of molten rock, and gets to stick a hammer into lava, although in between flows the tip of his walking stick bursts into flame and he can’t stop walking lest his boots—and he along with them—melt. He gives passing mentions to physicists such as Antoine Lavoisier, whose theory of heat as liquid was wrong, but inexplicably leaves off every giant of thermodynamics such as Lord Kelvin, James Prescott Joule, Rudolph Clausius, and Sadi Carnot. Barefoot, he walks on burning coals, and learns that “in firewalking as in life, your mind has to be in a certain place.” But those temperatures don’t compare with those of the supercollider, which generates controlled heat hotter than the center of a supernova. In such extreme conditions scientists study quarks, the building blocks of matter. Perhaps no amount of heat can reduce quarks into smaller pieces, and quarks are the end of the road. Then again, maybe not.

The Atlantic OceanBy Andrew O’HaganClassics of the essay form that look at what’s going wrong in the Anglo-American world, from youth violence to Hurricane Katrina.

Andrew O’Hagan has become one of the greatest practitioners of the worldly essay on the state of affairs, a reputation cemented by the British publication of The Atlantic Ocean in 2008. It is finally available in the U.S., though lovers of Alistair Cooke, another jet-stream traveler, should beware: this is no Letters From America. O’Hagan has a similar intimacy, elegance, range, and depth. But Cooke embodied the best of the Anglo-American bond as he rounded out the dimensions of a soaring and ever-more-free New World to listeners and readers in the Old. He believed and loved America. Whereas O’Hagan is critical of the West, as he sees the darker forces pulling the two sides of a narrow ocean closer and closer together into baser territories. He’s horrified at the violence that characterized the norm during his boyhood, a culture of abuse that reawakens in 1993 with the torture and murder of 2-year-old James Bulger at the hands of two 10-year-old English boys. On the other edge of the pond, Hurricane Katrina left him equally dismayed, as he followed Sam and Terry, two foul-mouthed relief workers who talked about how much they admired George W. Bush, all the while transporting a handgun in their truck, even burying it in the ground to get past a Volunteer Command Post military checkpoint. Sam, who is white, and Terry, who is black, talk a lot about race, each accepting the other’s racism masking as crude jokes. It’s enough to make one believe that the English-speaking people are beyond salvation. “The attempt to make sense of these things might be doomed to failure,” O’Hagan says in the collection’s final piece, where he writes about one of Bulger’s killers, Jon Venables. But not attempting to make sense of things is exactly what’s taking us down the spiral, and is exactly why O’Hagan is so necessary. “It feels very natural to me to have believed that writing could be a way of speaking up for all of us.”

The Miniature WifeBy Manuel GonzalesA darkly smart collection that circles time and space with an eagle-keen eye for the humanity of its characters.

The short-story collection from Manuel Gonzales is a promising debut—a volume of artfully structured tales that dine on science fiction and fantasy tropes before leaving cliché and expectation behind in a wild adventure through the human condition.

Gonzales’s most outlandish (or rather extraterrestrial) story, “Life on Capra II,” begins with a perhaps intentional nod to Robert A. Heinlein’s Starship Troopers: “Just as we bag that piece of shit swamp monster, the robots attack. Ricky goes down immediately, and that’s a fucking shame, because he was a good guy, and also he owes me—owed me—a pack of cigarettes …”

Other stories include that of a hostage aboard a hijacked airplane who, well beyond the point of Stockholm syndrome, has embraced his incredible 20-year aerial limbo as the only life left for him, and the titular story, “The Miniature Wife” about a scientist whose wife becomes inexplicably reduced to the size of a coffee mug, and, understandably, blames him for her condition. She spends her time carrying out a guerilla war of passive-aggressive acts against him that escalates with each passing day.

But every story’s ending need not be dark for Gonzales. Ever having fun with his readers, he writes a clever biographical and anthropological legend of the origin of clowns in “William Corbin: A Meritorious Life.” Clowns are those who now practice the lost arts of a long-dead Eastern European race of Klouns, “big-footed, of pale complexion, and with an over-expressive face, [who] would often steal the show through popular movement skits and drama tumbles and the performance of ineffable sleights of hand.” Regardless of fantastical concept, Gonzales carries off the task with his own ineffable qualities, and hopefully there will be more to come.

—G. Clay Whittaker