Where did you grow up?Washington, DC, just a few blocks from Politics and Prose bookstore.

Where and what did you study?I majored in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at Yale.

Your brother is also a popular writer. Was writing a self-evident career early on in both your lives?Certainly not in mine. Writing happens to be a good vehicle for my interests at the moment, but I often fantasize about doing something else.

Where do you live and why?I live in New Haven, Connecticut. My wife is a medical student at Yale.

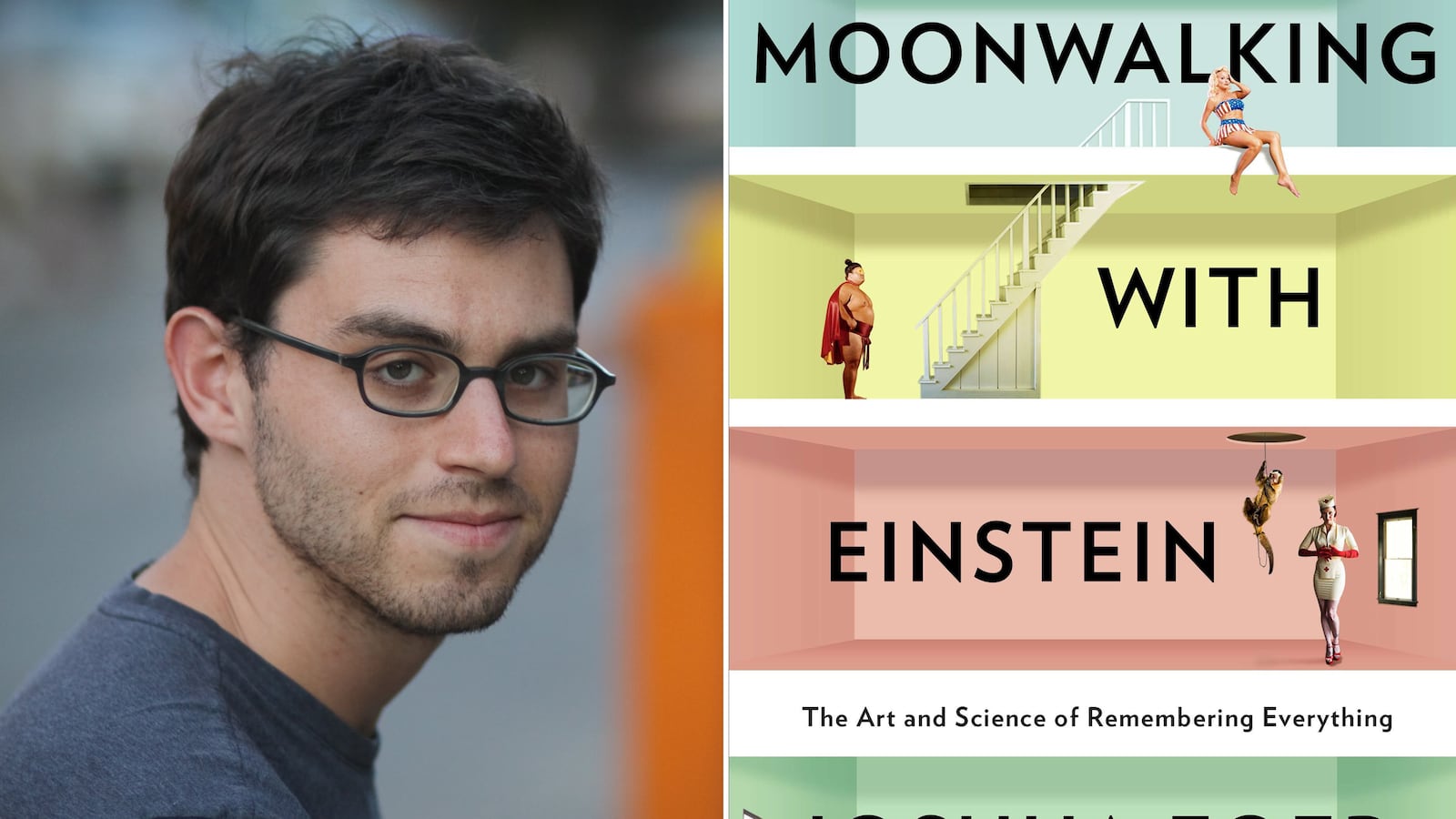

Before writing Moonwalking with Einstein, you were a journalist for a number of good magazines. At what point did the article you researched on memory competitions suddenly feel like a book to you?From the beginning of my reporting, it felt like there was a bigger story to tell than could fit in a single magazine article. But I think it took me a while to realize how the story could work as a book. In fact, the book about memory I first set out to write was going to be quite different from the one I ended up writing. For one thing, I was not supposed to be a character in it. Actually, this may sound surprising to anyone who has read Moonwalking, but the original model I had in mind when I started thinking about my book was John McPhee’s Levels of the Game. If I’d followed that path, it would have been a terrible book.

Is there one of your articles that you’re particularly pleased with, that you consider a good example of your journalistic writing?It’s rare that I’m proud of anything I write, but I’m proud of my recent New Yorker profile of a former DMV employee who spent 30 years trying to invent a more perfect language. Five and a half years ago, I had gone to a conference on invented languages, on an exploratory mission, fishing for a story. At that conference, I met John Quijada, the man I ended up profiling. At the time, his story hadn’t yet ripened into the wild, crazy tale it would become, but I stuck with him and stayed in touch, and when his story took a major turn for the weird, I was there to tell it.

How do you approach writing a 1500 word article differently from an 80,000 word book? Where are the points of expansion?A magazine story and a book are nearly as different as a photograph and a film. An article is typically read in one sitting, which means you’re not asking a lot of the reader’s time and energy. And that means you can get away with things that you can’t get away with in a book. If you’ve got a compelling subject, you can write your way around a less-than-compelling character, or a narrative arc that doesn’t actually transport the reader a great distance. An article that doesn’t hit every note can still work. But a book is typically read in multiple sittings, which means the story needs to have momentum behind it to compel the reader to pick it back up each time she puts it down. Sequencing—the careful striptease by which you reveal information to the reader—matters in an article, but it is absolutely essential to a book.

Describe your morning routine.I had a kid a few weeks ago, so my routine is in the midst of getting reshuffled. It used to be I’d get up early and make sure I was at one of the local coffee shops when it opened, at 7. These days I wake up half dazed, and maybe, just maybe, get a half hour of real work done before lunch. I’m looking forward to getting back to the old schedule.

What is your favorite item of clothing?ExOfficio boxer briefs. You can wash and dry them in like 30 seconds. As a traveler to humid locales, they’re utterly indispensible.

What is a place that inspires you?Back when I lived in Brooklyn, I’d sometimes take the Q train all the way out to Coney Island and back, and work on my laptop. There’s something about pushy New Yorkers looking over your shoulder that really makes you produce sentences.

Describe your writing routine, including any unusual rituals associated with the writing process, if you have them.I have a woodshop in my garage. If I’ve made good progress in the morning, I’ll reward myself by going out back to spend an hour making sawdust, before returning to work for the afternoon. Woodworking requires a completely different kind of thinking and problem-solving ability than writing. With writing, you take a set of facts and ideas, and you reason your way forward to a story that pulls them together. With woodworking, you start with an end product in mind, and reason your way backward to the raw wood. If you can’t envision the entire journey that a plank of wood will take on its way to becoming something finished, you will make uncorrectable mistakes. With writing, each step of creation justifies the one that comes before. With woodworking, each step has to justify the one that comes after. On a good day, I’ve had a chance to exercise both kinds of reasoning.

Is there anything distinctive or unusual about your work space? Besides the obvious, what do you keep on your desk? What is the view from your favorite work space?Several days a week, I work in the Young Men’s Institute Library in downtown New Haven. The Institute Library is New Haven’s greatest secret. It was founded in 1826, and is one of the oldest remaining private lending libraries in America. Membership is just $25 a year. I work at a big round oak table in a gorgeous old room that is like a little piece of the 19th century perfectly preserved in amber.

Describe your evening routine.I try as hard as possible not to work in the evenings. That’s family time. Wife time. Kid time. Baseball time (in season).

Do you have any superstitions?I’m an observant Jew, so yes, my whole life is structured by superstition.

Do you continue to keep up any of the memory training you describe in your book? When you write about it, it does sound feasible, but also sounds like a lot of work and commitment to maintain.Yes and no. I don’t memorize decks of cards anymore, but I do try to memorize speeches, when I’ve got the time to do that. I recently memorized the entire Lingala-English dictionary, to help me prep for a reporting trip to the Congo.

I was thinking about the appeal of feats of memory, and thought back on Giordano Bruno, and got to thinking that memory demonstrations are akin to magician’s illusions—they seem otherworldly, we admire the skill and determination required to pull them off, and a part of us cannot imagine that we could pull it off ourselves. What are your thoughts on memory feats and magic?Feats of memory are exactly like magic: Utterly unbelievable, until you find out it’s all just a simple trick—one that you can do yourself.

If you could bring back to life one deceased person, who would it be and why?Athanasius Kircher, the eccentric seventeenth-century Jesuit polymath, collector of curiosities, and borderline crank. He’s my hero.

Was there a specific moment when you felt you had “made it” as an author?Yes, the first time I saw a stranger reading my book in public. I’d tried my best to prepare myself for the possibility that this might, someday, happen. But still I managed to have a completely uncool freak out. To the guy I nearly mauled on Shattuck Avenue in Berkeley… I apologize.

What do you need to have produced/completed in order to feel that you’ve had a productive writing day?Most days: a paragraph. It’s the days when I disappear down the Internet rabbit hole that are the real problem for me. So long as that hasn’t happened, I consider the day a success.

Tell us a funny story related to a book tour or book event.I was standing by the door, about to go on stage at Elliott Bay in Seattle, when a young couple got out of their seats and frantically rushed out past me. On her way out the door, the woman whispered to me, “Sorry, you lost out to Sacks.” I thought to myself, “Yeah, no hard feelings, if Oliver Sacks were in town, I’d probably choose to see him over me, too.” But, as I was walking up to the podium, it suddenly hit me. It wasn’t Sacks I’d lost out to. That’s the wonderful thing about Seattle: in New York, a horny couple would never have the common courtesy to explain to you why they were leaving your book reading.

What advice would you give to an aspiring author?There is a short window at the beginning of one’s professional life, when it is comparatively easy to take big risks. Make the most of that time, before circumstances make you risk averse.

What would you like carved onto your tombstone? "Joshua Foer. 1982-2102"

What is your next project?It’s about the world’s last hunter-gatherer societies, and what they can teach us. As part of my research, I’ve been spending time in Central Africa living with a group of Mbendjele pygmies.