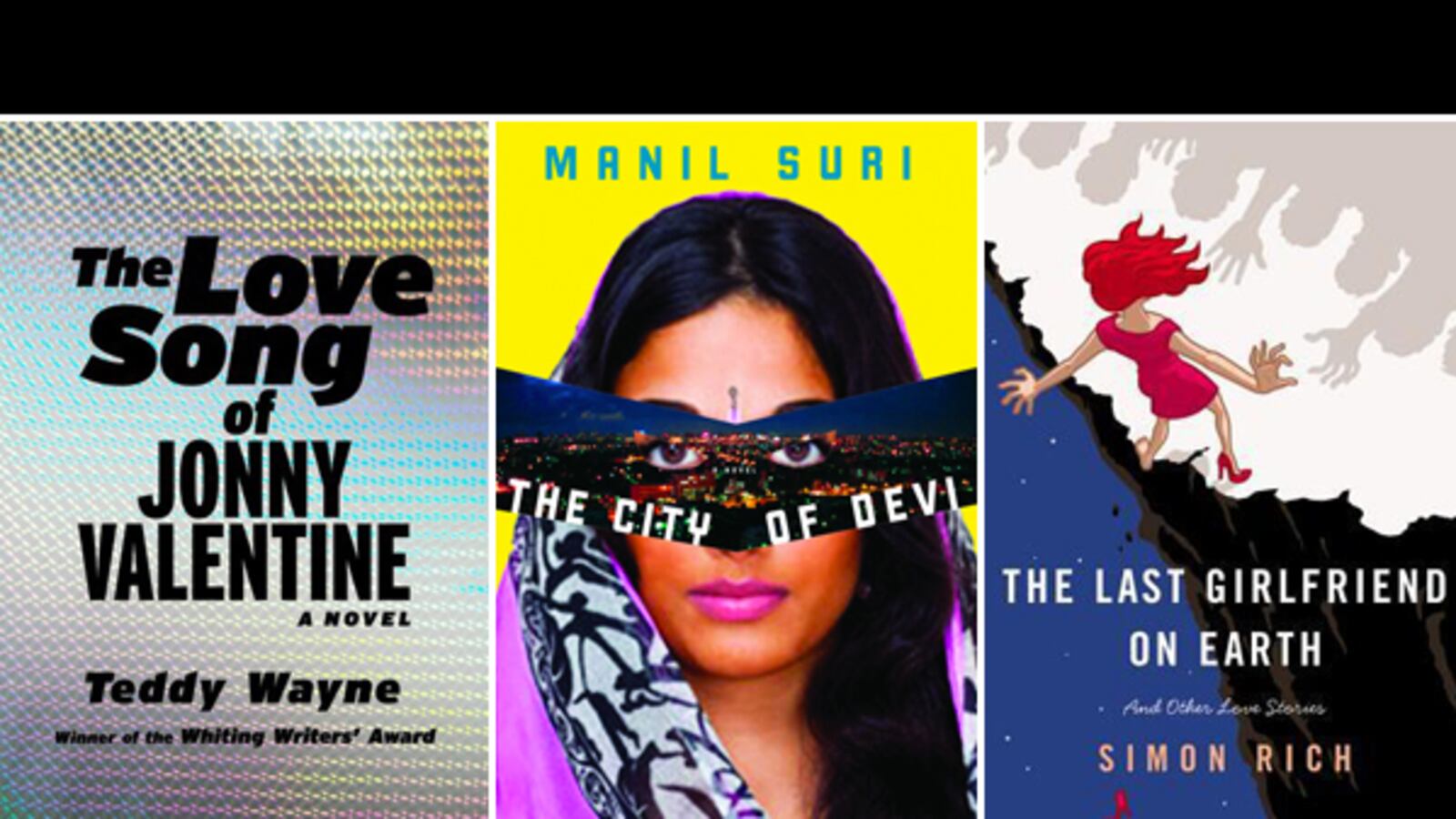

The Love Song of Jonny Valentine by Teddy Wayne

A pre-teen pop idol searches for his voice.

It’s not easy being a tween. Eleven-year-old Jonathan Valentino—aka Jonny Valentine—isn’t good at talking to girls, doesn’t understand why his parents separated, and isn’t even allowed to use the Internet by himself. Given the choice (which he isn’t), he would much rather play his favorite video game, Zenon, than study math. After all, it’s hard to see the point of doing homework when your album has gone triple platinum.

Jonny’s stardom is undeniable—nothing short of Bieberesque. Still, he doesn’t exactly have it made. His grueling tour schedule is wearing him down and he’s overheard enough conversations between his mother/manager Jane and the execs at his record label to know that the future of his career is in question. Concert tickets and album sales are lagging, and as he hits adolescence, Jonny’s entire act will require a massive overhaul. There’s also a bigger, unspoken question looming: Does Jonny even really want to be a pre-teen pop idol?

Jonny may still be a child, but his problems are decidedly adult. As the February 14th culmination of his tour draws near, he is forced to navigate everything from his mother’s drug problem to the reappearance of his long-gone father—not to mention the emergence of his own libido. Depicting the inner life of a protagonist who is not yet a full-fledged adult is no small feat, but author Teddy Wayne pulls it off masterfully. Jonny’s innocence could be a liability in a story so complex, but Wayne deftly uses it to show that Jonny, bright and conflicted, is as much an observer of his life as a participant in it. Jonny knows how to perform—but it’s not clear whether he can write his own act, too. In the end, there’s no business like show business, except, maybe the business of growing up.

The Last Girlfriend on Earth by Simon Rich Sweet and zany tales of young love from the dog park to outer space.

What do a condom awaiting its fate in a wallet and a CIA agent who uses his invisibility serum to tail his ex-girlfriend on a date have in common? Like every other character in The Last Girlfriend on Earth, they desperately want love.

Humorist Simon Rich’s compendium of heartbreak is divided into three sections of very short and sweet stories about the quest for love: Boy Meets Girl, Boy Gets Girl, and Boy Loses Girl. Some of these stories are all punch-line, like “Dog Missed Connections” (“Not sure if you’re male or female, but either way, I’d like to smell your genitals”) or “NASA Proposal” (in which a male astronaut proposes “to determine the effects of zero gravity on human mating” with his sole colleague in outer space, a woman). Other tales get a little messier—“Occupy Jen’s Street,” for instance, follows the plight of a sexually frustrated activist who stages a protest to demand the woman he’s been pursuing go out with him. His movement gains traction, but will Jen ever come around?

No matter how zany things get, there’s an endearing simplicity at the heart of these inventive tales. Shy Oog wins Girl away from arrogant Boog. Master of deduction Sherlock refuses to put together the evidence that his girlfriend Alyssa is cheating on him. Love doesn’t always conquer all, but these stories suggest Rich thinks it certainly ought to. His story “Center of the Universe” spells out as much: Even God would rather keep his girlfriend’s affection than rule the universe.

See Now Then by Jamaica Kincaid As years go by, a domestic idyll turns dark.

In Jamaica Kincaid’s first new novel in 10 years, family life comes under the microscope. See Now Then is the story of Mr. and Mrs. Sweet and their two children Persephone and Heracles. The Sweets’s days pass as though in a dream. Past and present merge and divide as the project of “the seeing of Now being Then and how Then becomes Now”—the lifelong project of trying to understand experience itself, that is—quietly grips them.

Full of love, Mrs. Sweet sings, bakes, gardens and knits for her family. But all is not well in her marriage. Mrs. Sweet “could not see it and could not understand it even if she could see it: her husband, the dear Mr. Sweet, hated her very much.” To Mr. Sweet, his wife’s very voice is a “red light, irritating and interrupting everything that was pleasant.” He often imagines her dead.

Kincaid weaves Mr. and Mrs. Sweets’ interior worlds into the routine of their daily lives as Mr. Sweet’s passive hatred intensifies and the gulf between Mr. and Mrs. Sweet’s experience grows. What starts as a domestic idyll turns out to be something much darker. “Things change!” Mr. Sweet tells Mrs. Sweet, articulating in just two words See Now Then’s refrain: “right now is so certain, right now is forever; what is to come will make, distort, and even erase right now; right now will be replaced by another right now: and right now is all there is over and over again.”

City of Devi by Manil Suri

Holding on to love through Mumbai’s end-days.

The threat of a nuclear attack from Pakistan has emptied out Mumbai. As Hindus and Muslims turn on one another and “the curds of social order begin to thicken and clump” into lawlessness, Sarita sets off in search of her husband, clutching one of the last pomegranates in the city. Though she doesn’t know it, Sarita’s not the only one trying to find Karun, a gentle physicist who vanished days before without explanation. Unscrupulous, charming Jaz is after him too—for reasons she can’t even fathom.

Wry in its diagnosis of pre-apocalyptic Mumbai’s tensions (for political reasons, “Bugs Bunny has become ‘Khatmal Khargosh’”) and perceptive in its development of Sarita and Jaz’s identities, the first half of City of Devi is a pleasure to read. In Bombay native Mani Suri’s hands, the early scenes of a city in collapse are something to marvel at too. Suri’s taxonomy of factions and sub-factions that emerge as the city unravels is fascinating for its precision and detail.

But as the story reaches its climax, leading Sarita and Jaz to Devi, the unlikely child goddess said to protect the city, Suri struggles to convincingly connect the pieces. Sarita, Karun, and Jaz’s storylines converge, but by the final chapters, their triangle has transformed from uncomfortably believable to inexcusably mawkish. It’s a disappointing end to a world built with so much creativity and care.

Drinking With Men by Rosie Schaap

A heartwarming tale of a life lived in bars.

“They were a tribe and I wanted in,” writes Rosie Schaap, in the opening pages of her beautifully rendered memoir of a lifetime—over “13,000 hours” and counting—spent drinking, talking, reading, flirting and working in bars. Schaap got started young, regularly sneaking into the bar car of Metro North trains to read commuters’ fortunes in exchange for beer. But it’s the camaraderie, not the alcohol, that she comes to depend on as she struggles through her teens and twenties, alighting from Connecticut to California, Dublin, Vermont and then, inevitably, New York City. Shiftless and often lonely, she comes to find solace, friendship and, eventually, purpose as a regular in a series of bars and taverns, each so lovingly rendered that it's easy to overlook the dangers inherent—especially for a woman—in such devotion. But while Schaap rubs up against melancholy, she mostly avoids the darker issues of the drinking life, opting instead for heart and abundant humor. These days, Schaap has done more then find her tribe; she's become its de facto spokesperson, penning the popular “Drink” column in the New York Times Magazine. But she has also remained true to her low-lit, mahogany past, and on slow Tuesday afternoons can still be found at a certain Park Slope watering hole, pouring pints and shots for a crowd of friends and locals—her people, all.

—David Goodwillie