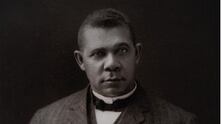

Against this dismal and deteriorating landscape, Booker T. Washington struggled valiantly to build one of America's great educational institutions, Tuskegee.

Starting with one dilapidated cabin, whose roof leaked so badly that a student had to hold an umbrella over Washington's hand when he lectured on wet nights, Washington built Tuskegee into the largest and wealthiest school in Alabama by 1900, attended by more students than attended any of the state's own (all-white) universities. He raised funds for buildings and to acquire land. Tuskegee's main business was to train teachers for segregated black primary schools. It also offered instruction in advanced farming techniques, brick making, and other skilled trades. Unusually for the era, Tuskegee was coeducational from the first.

Tuskegee's students could hardly afford the cost of tuition. Washington threw himself into the work of fundraising, achieving spectacular success by gaining the confidence of the richest industrialists of the North. They were impressed by results, and reassured too by the conservatism of Washington's philosophy.

Education, skills acquisition, capital accumulation: these accomplishments, not political protest, were Washington's path to black progress. As black Americans became indispensable, so they would overcome animosity and achieve progress. Years before Gary Becker won a Nobel Prize for the idea, Washington was already convinced of the economic irrationality of discrimination. He wrote in Up From Slavery:

[T]he whole future of the Negro rested largely upon the question as to whether or not he should make himself, through his skill, intelligence, and character, of such undeniable value to the community in which he lived that the community could not dispense with his presence. I said that any individual who learned to do something better than anybody else—learned to do a common thing in an uncommon manner—had solved his problem, regardless of the color of his skin, and that in proportion as the Negro learned to produce what other people wanted and must have, in the same proportion would he be respected.

It's true, as WEB DuBois and other later critics contended, that Washington avoided direct criticism of the prejudices around him. This was policy, not cowardice.

I early learned that it is a hard matter to convert an individual by abusing him, and that this is more often accomplished by giving credit for all the praiseworthy actions performed than by calling attention alone to all the evil done.

- UP FROM SLAVERY

It was Washington's method to seek allies and friends - to avoid fights he could not win - and to pursue his more controversial goals indirectly and discreetly. As Norrell reminds us, later researchers have discovered that Washington and Tuskegee financed the most important court challenges to segregation in the 1890s and 1900s - almost all of them tragically unsuccessful. Washington worked covertly because he needed to protect his university from real and violent danger.

Booker's keen sense of modern mass communications led him to engage the services of a professional photographer, Frances Benjamin Johnston, of Washington, D.C., to make a visual record of life on the Tuskegee campus, which the school would use in promotional efforts. WHen that work was done, Booker sent Johnston to make photographs of some of the little Tuskegees [i.e., schools launched by Tuskegee alumni]. She traveled by train to the Ramer Colored Institute School, ten miles south of Montgomery, where late one evening she was met by George Washington Carver and Nelson Henry, the Ramer school's founder and principal for the past six years. As Ramer drove the attractive young Johnson from the station toward his house, they were accosted by a group of white men who drew the conclusion that Henry had breached racial etiquette and shot at the couple three times. Henry fled Ramer as white patrols declared their intention of beating him to death. Carver walked all night to get away. Somehow Johnston escaped on a train. An investigation by the governor of Alabama concluded that the incident was the work of a few hotheads …. But Henry was unwilling to risk a return to Ramer, notwithstanding the years invested there. Blacks in Ramer had advised him not to come back. The school closed ….

(Norrell, p. 271)

Washington himself lived at constant risk of assassination.

Contra his critics, Washington understood very well the world around him. He died at 60, and it's hard to escape the feeling that his death was accelerated by the stress and strain of wearing the "mask that grins and lies." If he did not challenge that world as later critics wished he had, it was because he was working to change it.

The protest narrative by which Washington was later criticized makes two mistakes: it underestimates black weakness in the post Civil War South - and (more seriously) it grossly overstates white goodwill. The protesters of the 1950s and 1960s made headway by shaming white America into changing its behavior. They were supported by white America's reaction against Nazi racism and - much more - by the imperatives of Cold War competition. A federal government that felt itself to be competing for influence against the Soviet Union in Latin America, Africa, and Asia could not afford to indulge apartheid and racial violence home.

That, however, was not the world of 1900. The world of 1900 was a world in which Southern whites (and many Northern whites too) rejected Washington's pre Gary Becker vision of gains from trade in favor of a proto-fascist vision of a racial struggle for existence.

Norrell references an article published in 1905 by Thomas Dixon, one of the bestselling authors of the time, whose novels would inspire the movie, Birth of a Nation. In the Saturday Evening Post - the "60 Minutes" of its day - Dixon outlined a fierce critique of Washington's philosophy of black self-betterment.

The real tragedy would begin when black men and white men began competing in the industrial workplace. Would the southern white man allow the Negro to master his industrial system, take the bread from his mouth, and place a mortgage on his house, as in fact Booker had promised? Dixon emphatically answered "no": "He will do exactly what his white neighbor in the North does when the Negro threatens his bread - kill him!"

(Norrell pp. 325-326)