I did not come to essay writing immediately, but fell in love with the form after fiddling around with fiction and poetry, even publishing books in those two genres. In time I came to see the essay as so capacious and flexible that it could accommodate the storytelling impulse of fiction and the associative, quicksilver moves of poetry, enabling me to draw on my training in both. But this is how it first came about. By chance I happened on a Selected Essays of William Hazlitt in the bookcase of a summer bungalow I was renting in Wellfleet, and the passionate, hot-headed Hazlitt turned me on to his gentle, humorous friend Charles Lamb and their literary forerunner, Michel de Montaigne, and by then I was hooked. Virginia Woolf came next, with her dazzling, sensuous essays and literary criticism. She too wrote about Montaigne and Hazlitt, because all the great essayists seem to refer to, draw strength from, and converse with one another: as I tried to show in my anthology, The Art of the Personal Essay, the tradition is a loose chain that stretches over centuries, and the surprising thing is how intimate, candid, and trustworthy the voices from near and far remain. The best essayists are supremely companionable. They become like your old friends. I include in my personal friendship circle Montaigne, Hazlitt, Lamb, and Woolf, George Orwell, James Baldwin, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Max Beerbohm, Robert Louis Stevenson, E.B. White, Mary McCarthy, Susan Sontag, Roland Barthes, Walter Benjamin, Edward Hoagland, Seneca, Edmund Wilson, and many others. I am indebted to them all, and hope to continue to steal from them, unconsciously or otherwise.

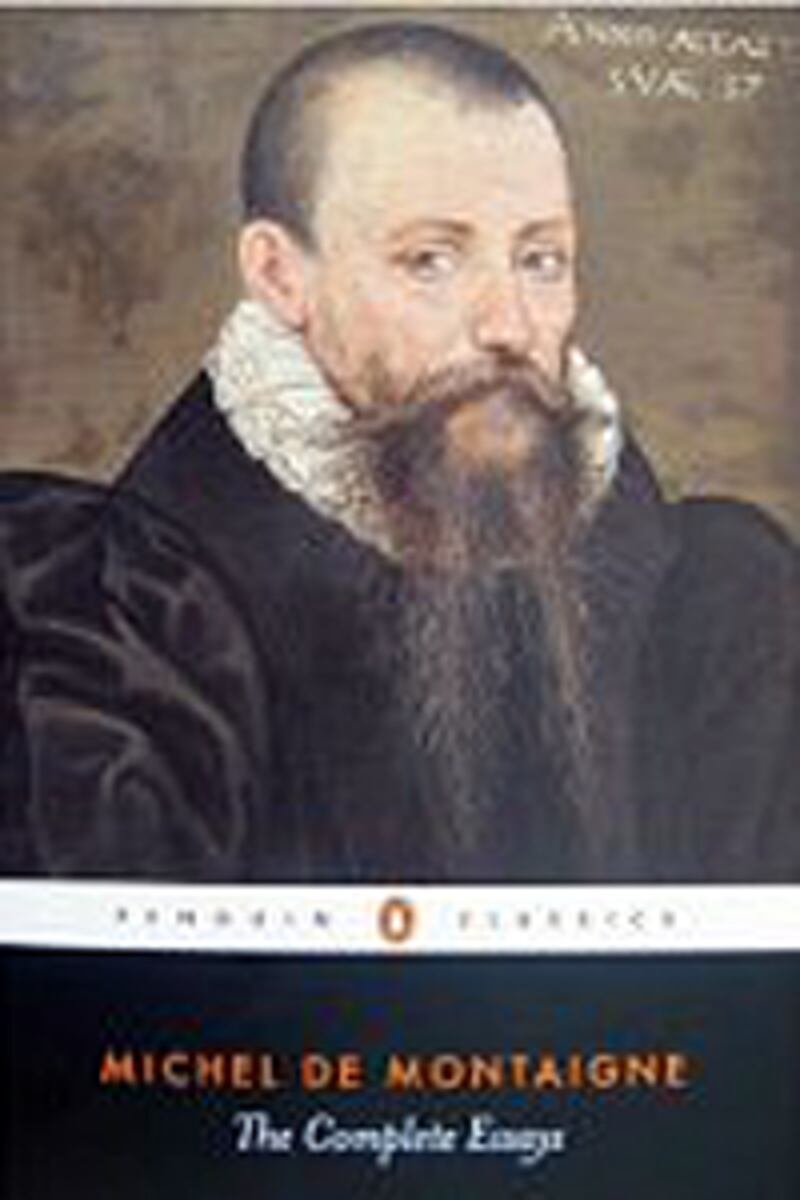

The Complete WorksBy Michel de Montaigne

This is the one inexhaustible book anyone interested in the form must have. (I much prefer the Donald Frame translation, which is available from Everyman). Montaigne really thinks on the page, right in front of you. He’s playful and uses a remarkable amount of humor and irony, much of it self-deprecating. He sees himself as changeable and inconstant. He had this insight that man is divided, contradictory—the self is fluid and memory is unreliable. You can draw a straight line from Montaigne to Freud, in viewing one’s self as basically strange, mysterious, full of paradoxes and secrets. His main subject was—himself. He studied himself in almost a scientific way, not because he thought he was unique, but because he regarded himself as ordinary enough to illustrate universal truths. What’s unique about him is the great mental freedom he exhibited, allowing his mind to drag him from subject to digression, often without pursuing any formal argument. It’s like free association. This all-over style makes him the Jackson Pollock of essayists. He established a wide template for the essay: everyone after him narrowed it down.

Selected Essays of William Hazlitt 1778–1830

One of the greatest prose stylists in the English language, Hazlitt wrote with enormous power and cogency, drawing on emotional heat and a strong intellect. You’ve only to read his contrarian “On the Pleasure of Hating,” or his paean to boxing, “The Fight,” which is one of the classics of sports writing, or his enthusiastic pieces about art, “On the Pleasure of Painting” and “On Gusto,” or his outspoken memoir of Coleridge and Wordsworth, “My First Acquaintance with Poets,” to see how close he got at all times to his feelings, how thin-skinned, irascible, and yet generous and broad-minded he could be. Hazlitt was, in short, a character. You get swept along by his rhetorical energy, his rants; and if a part of you thinks, Now, wait a minute—! that doesn’t bother Hazlitt; he’s not out to win any congeniality awards; he just wants to convey himself, in the fullest terms possible. And for that, I can’t help loving him.

Essays of EliaBy Charles Lamb

In this, one of the beloved comic classics of English literature, Lamb chose to speak through a made-up clerk named Elia, in order to have more fun with himself and his cheeky, mischievous narrator. Lamb had been a clerk for many years, and his perspective was ever that of a low-status outsider, defending the less powerful in society, such as chimney sweepers or poor old women. In “A Bachelor’s Complaint of the Behavior of Married People,” he pokes fun at the complacencies of middle-class couples, while in his heart-wrenching “Dream-Children,” he fantasizes about the offspring he might have had. His hilarious parody-fable, “A Dissertation Upon Roast Pig,” traces the supposed genesis of that culinary delicacy. “New Year’s Eve” moves from the frivolous and festive to the tragic, without missing a beat. Blessed with a sense of humor that is by turns delicate and preposterous, tender and sharp-edged, and an elegant prose style that is always seizing on the right, unexpected word, Lamb is to be savored, sentence by sentence.

James Baldwin: Collected Essays

We now have enough perspective to see that Baldwin, who died in 1987, was a giant, a true American master of the essay. His central subject was race, about which he wrote with cauterizing honesty and clinical analysis; but he also had brilliant insights into adolescence, family life, and the whole process of growing up, as can be seen in his magnificent, brief essay, “Notes of a Native Son,” and his longer, no less shattering memoir, “The Fire Next Time.” It was Baldwin’s special gift to move gracefully between the autobiographical, historical, sociological, political, and the cultural. His prose style was alternately clear and baroque, blunt and ornamented: in any case, his own. Self-taught, he taught a whole generation of essayists how to be relevant, how to command attention from the distracted contemporary reader. He had been a boy-preacher and he could always rise to the pulpit, especially at the end of an essay; but he could also be spry and surprising, as in his movie criticism. He was incapable of writing a dull page.Moments of BeingBy Virginia Woolf

This collection of essays, memoir pieces, and addresses was put together after the author’s suicide by her husband, Leonard. Woolf was not only a great novelist but a first-class essayist, as can be seen by her literary criticism (collected in The Common Reader as well as The Death of the Moth and other volumes. Still, the one book of hers I keep returning to is this one, Moments of Being, partly because it is so instructive in delineating the process of writing for oneself or for others. The key document in that regard is “A Sketch of the Past,” which she began as an attempt at a memoir and never finished. The fragment that remains is one of the most beautiful, moving and searchingly thoughtful inquiries of self and memory that we have. The portrait she draws of her mother is much more unguarded than those she had attempted earlier in memoir pieces written for publication. We see that more public, juicy, persuasive side of her prose in several other essays here, often treating autobiographical materials delightfully. But it is only in “A Sketch of the Past” that we have the privileged sense of listening in on her mental process, while she ruminates in the privacy of her study—a kind of throwback to Montaigne’s free-association method.

At the core of every essay is a tracking of consciousness, and Woolf, Montaigne, Baldwin, Hazlitt, and Lamb all fulfill that contract gloriously.