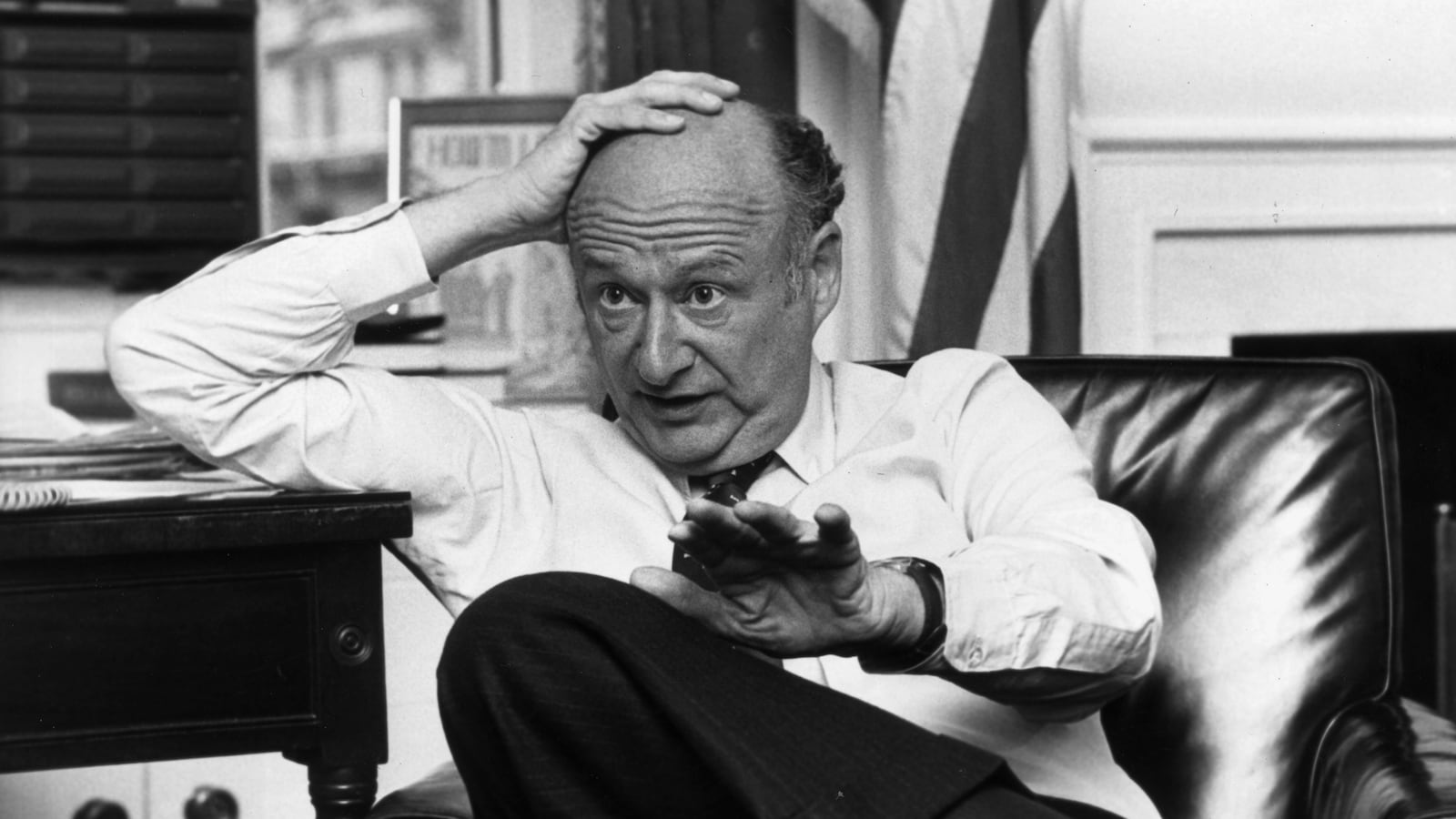

Watching the new documentary about his life last Saturday night, I kept asking myself, who is the Republican Ed Koch?

Koch helped kill one species of Democratic politics and incubate another. In the late 1970s and 1980s, he helped kill the brand that opposed gentrification, which saw junkies and porn shops in Times Square as superior to glitzy chain stores. He helped kill the species that supported public-sector strikes even when they inconvenienced and alienated ordinary working people. He helped kill the species that couldn’t care less what the bond markets thought and which viewed the police with suspicion, if not contempt. He helped kill those things by fighting viciously, and shrewdly, against those in his own party who believed that the Reagan presidency was a fluke. Koch, who spent most of his mayoralty in the Gipper’s shadow, was one of a handful of key individuals and institutions—Al Gore, William Galston, and Elaine Kamarck, the Democratic Leadership Council, The New Republic—that insisted that by electing Reagan, the American people were telling Democrats that they needed to fundamentally change. Between Walter Mondale’s defeat in 1984 and Bill Clinton’s victory in 1992, these Democratic reformers clashed again and again with Democratic fundamentalists like Mario Cuomo and Jesse Jackson. Ultimately, they turned the Democratic Party from the party of nuclear freeze to the party of nuclear modernization, from the party of defendants’ rights to the party of more police, from the party of the AFL-CIO to the party of NAFTA, from the party of government stimulus to the party of deficit reduction, and from the party whose presidential candidate couldn’t get angry when a CNN anchor asked what he’d do if someone raped and murdered his wife to the party whose presidential candidate signed the death warrant for a man so severely retarded that during his last meal he asked if he could leave the dessert for later.

Koch thrived in that era because he was not a conciliator. He understood that the only way to retain the support of the working-class whites who supported Reagan was to risk a political confrontation with his party’s African-American base. From his closure of Sydenham Hospital in Harlem to his statement that any Jew would be “crazy” to vote for Jesse Jackson to his response to the racially motivated murder of Yusuf Hawkins, Koch seemed to pride himself on defying, and even insulting, New York’s black elites. And he got his comeuppance in 1989 when David Dinkins, the African-American borough president of Manhattan, beat him in the Democratic primary. But Dinkins, although more decent than Koch, could not speak to the fear and resentment of New York’s white working class, and eventually surrendered the mayoralty into Republican hands. Among the most striking comments in the Koch documentary comes from the Rev. Calvin O. Butts III, pastor of Harlem’s Abyssinian Baptist Church, who calls Dinkins a good and smart man who lacked the toughness to be mayor. But for all his troubles with Koch, Butts told The New York Times that “if you’ve got to have a mayor for New York City, you need a guy like Ed Koch because he’s a rough-and-tumble kind of guy who speaks up and fights back.”

For the time being, the Democratic Party does not need people like Ed Koch. The party’s intramural brawls over crime, affirmative action, welfare, deficits, and military intervention are largely a thing of the past. The African-American versus white ethnic divide that once bedeviled northern Democrats has been superseded by the revulsion that both groups feel toward the Southern-dominated GOP. Al Sharpton, who once terrified and enraged white Democrats, now hosts a show on MSNBC, where he sounds just like every other Democratic talking head. Democrats may still fight with each other over tactics, with liberals forever insisting that Barack Obama isn’t pushing their agenda aggressively enough. But the ideological conflicts have largely disappeared. In 1988, when Koch campaigned for Al Gore against Jesse Jackson and Michael Dukakis, the Democratic primary was a nasty showdown between left and center. In 2016, if Hillary Clinton squares off against Andrew Cuomo or Mark Warner or Deval Patrick or Joe Biden, it’s hard to imagine them disagreeing about almost anything at all.

The Ed Koches of today are in the GOP. Like Democrats under Reagan, today’s Republicans are entering a vicious and fascinating contest between people who think the Obama presidency is a fluke and those who don’t. Reformers insist that to compete, Republicans need to embrace immigrants’ rights, stop battling Obamacare, and accept core elements of the welfare state. The most successful of them, like New Jersey’s Chris Christie, are appealing to Obama voters in the same way Koch appealed to Reagan voters: by declaring independence from those elements of their party that alienate the political center. It’s a more pleasant time to be a Democrat, but a more interesting time to be a Republican, especially if you don’t mind making enemies within your own ranks. Ed Koch would love it.