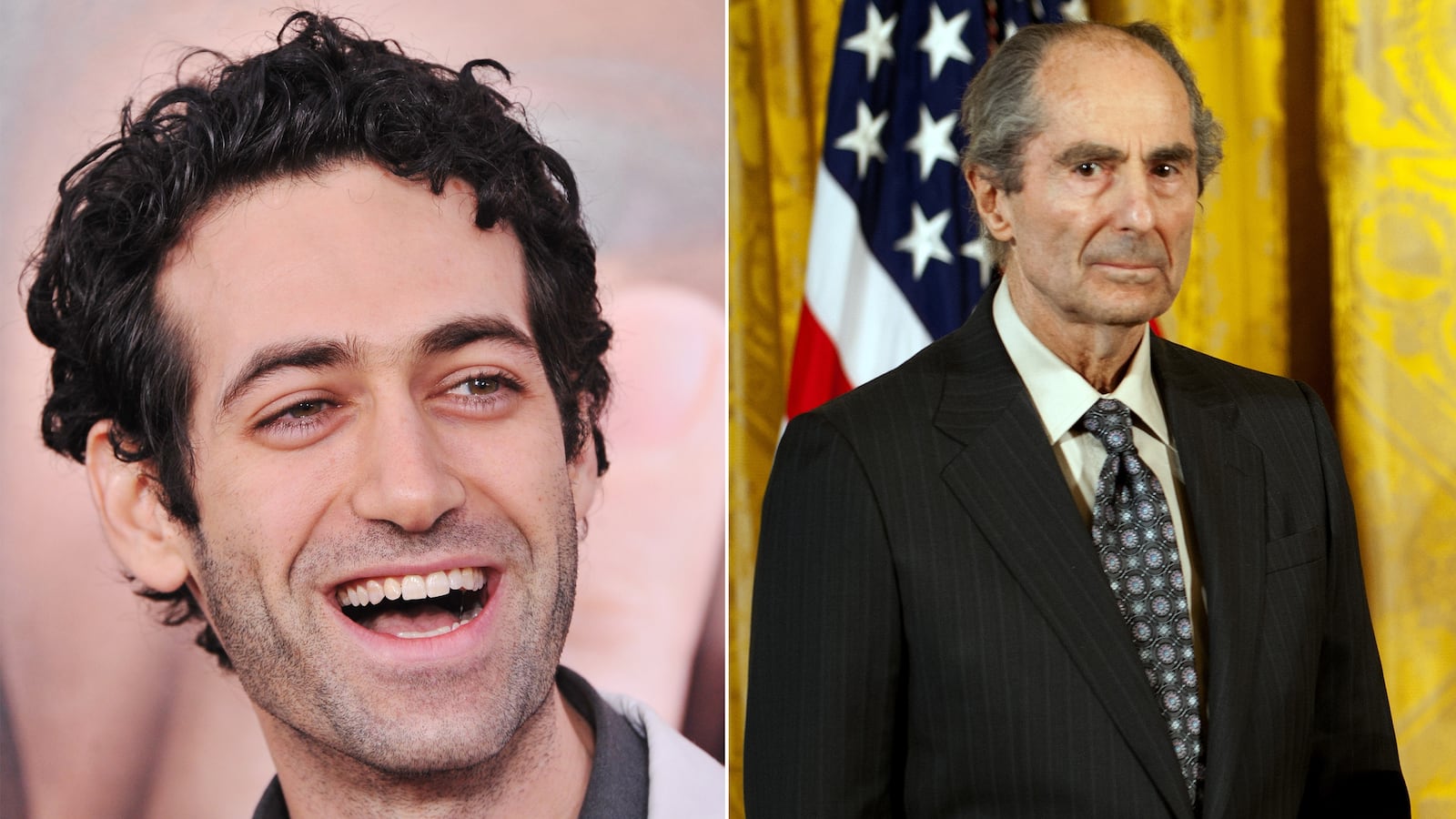

Dear Philip Roth,

Look, I have to apologize. You told me to quit writing. It was a terrific moment in my life. I went and wrote an essay about it and now people are angry. Elizabeth Gilbert is angry. People listen to her. They love her. Now they’re not happy with you. But then people are reading negativity into an incident where there was none. Having been there, and lived through it, and with the backlash, I wanted to write you and say I’m sorry. Since I don’t have your address, I’ve chosen to reach you through the media. I hope you get this.

First, let me say that it was not the first time I had been given that same advice to quit writing. Though it’s cliché to bring up one’s grandparents when discussing the inspiration behind becoming this or doing that, because you and my grandfather remind me of each other and have both played some role in my becoming a writer, I must talk about him now. He lived and worked at his loft on West Broadway, and when I paid visits to him, he’d come out of his studio, though only for a brief time, for he had to get back to work, and usually right away he’d ask how the writing was going. Before I’d answered him, however, he would have already told me not to be an artist, that I was setting myself up for a miserable existence, and that, if indeed I had to do this, to at least ... at very least ... marry a wealthy woman. “Forget what you’ve read about the garrets and the gutters, there’s nothing noble about poverty! If you have to write, make sure she’s got bucks!” “But what about love!” To which he would respond, “Shut up!”

Next, my grandfather would ask me what time I was waking up each day. Anything after 4 a.m. was too late. I was being lazy. Yes, 4 a.m. was the time to get up. This was when an artist should be getting to work. Before the farmer. Before the world. 4 a.m.! “Do you want to make good art, or crap? “You get out of it what you put into it.” “Use it or lose it.” These were his lines, and in the few minutes that we would speak he’d use them on me, like he was Bobby Knight or Bill Parcells. He had a round, very wide face, light eyes full of pride, a dimpled chin, a bald pate with a gray fringe. Why bring up his features? Actually, they are relevant. Because after his words on being an artist, and before returning to his studio, he’d say to me, “I used to be the most handsome guy in any room. But God’s great joke is to make us all look so ugly at the end. Well, anyway, Julian. That’s it, I’ve got things to do.”

Other advice from my grandfather: don’t talk about your good luck; you’ll live if you’re lucky; get back to work; shut up.

Mr. Roth, my mother always used to say to me, “Know your audience.” As far as our encounter went, it’s fair to say that you knew yours. When it comes to writing, I am of your school. It’s a brutal field, not warm at all, filled with disappointment. From where I’m standing, I wouldn’t even say you were giving me advice. We were just talking about making art.

Again, I’m sorry if my piece has led to some bad press. (My grandfather never said anything about all press being good press, but he wasn’t into the press, and I’d venture to say that you aren’t either, so I want to try to put a positive spin here.) But clearly you were not comparing writing to all the very worst professions (lawyer, stockbroker, real estate developer, etc). And as far as my piece in The Paris Review, it had something to do with meeting a hero. It had less to do with one of the greatest authors of the last century’s advice to a young novelist. And what I don’t want missed here is its central point, born out of the announcement of your retirement, which addressed one of the reasons why to write at all if writing is, as you told me, “just torture. Awful.” To keep that point from being lost, I will quote from the essay that has led to this apology:

“In the two weeks that followed our exchange, I’ve mentally replayed the moment again and again. And the conclusion I’ve most often drawn was that if I hadn’t been drugged…by the fact that he was actually engaging me in a conversation about writing, I would have asked him not whether he would have traded in all the celebrity, the money, and the sex to have lived the more plain existence of, say, an insurance agent. No, I would have asked him about boredom. And though I have only one novel published—and experienced none of the success of Roth—I still feel strongly that the one thing a writer has above all else, the reward which is bigger than anything that may come to him after huge advances and Hollywood adaptations, is the weapon against boredom. The question of how to spend his time, what to do today, tomorrow, and during all the other pockets of time in between when some doing is required: this is not applicable to the writer. For he can always lose himself in the act of writing and make time vanish. After which, he actually has something to show for his efforts. Not bad. Very good, in fact. Maybe too romantic a conceit, but this, I believed, was the great prize for being born … an author …

And now Philip Roth has told us he will no longer write. I wonder, what will he do when boredom sets in?”

One last time, I’m sorry.

Sincerely,JT