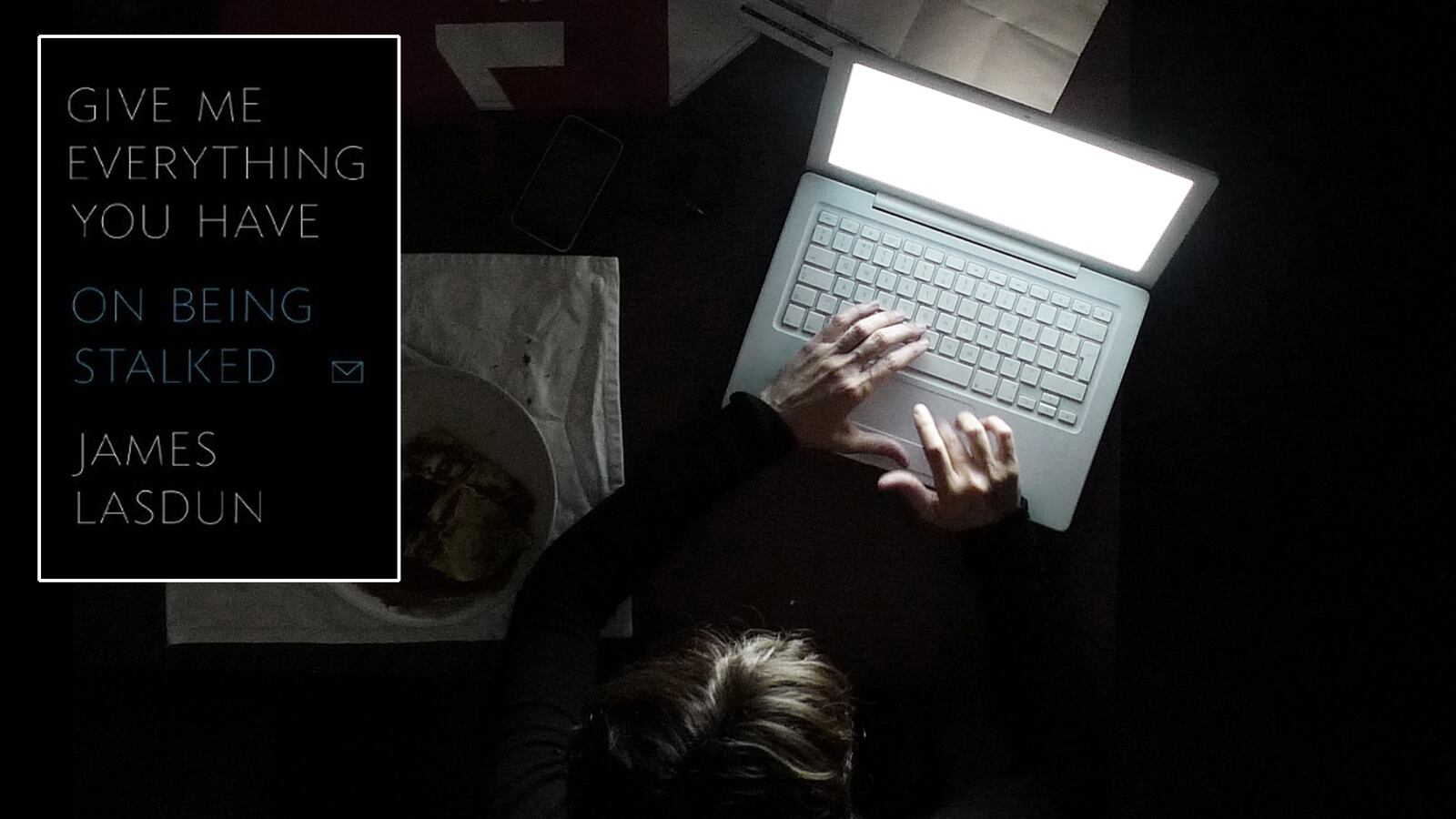

“Spite has never had such an efficient instrument at its disposal,” writes James Lasdun in his searing new memoir, Give Me Everything You Have: On Being Stalked. He’s referring to the Internet, via which a stalker persecuted him with the same terrifying, unstoppable facility as deployed by the bullies and trolls who, the headlines report with increasing frequency, hound the vulnerable to the point of suicide. “With the internet the scale of alliances that the oppressor can suggest is limitless,” suggests Lasdun with hard-won insight, “and the feeling of isolation in the victim becomes correspondingly acute.”

Yet Lasdun, a New York–based British author of two acclaimed novels, four short-story collections, and four volumes of poetry, isn’t your typical cyberbullying victim. A married, middle-aged father who leads a deliberately circumscribed life, he was unschooled in the Internet’s various forms of communication when he found himself subjected to a vicious online campaign whose stated objective was to “ruin” him. His prior illusory sense of immunity from such a threat—“an event from the larger world,” as he puts it, which “arrived at my own fortress door, despite my skepticism about the likelihood of such a thing ever happening”—lends his narrative, already grimly fascinating and stunningly well written, a chilling universality. What befell him could befall anyone.

It all begins innocently enough. “Nasreen,” an Iranian-born 30-something in a creative-writing workshop led by Lasdun, submits some novel chapters that he deems praiseworthy. As her thesis adviser, he meets with her a few times during his office hours. Then a couple of years later, when she has graduated and he’s no longer teaching in the program, she seeks him out for advice on her novel. A vague friendship, conducted almost entirely over email, is struck up, but once Nasreen’s romantic intentions become apparent—and she starts emailing many times a day—Lasdun gently rebuffs her.

So, obsessive love curdling into all-consuming hatred, she embarks on an impassioned vendetta, sending a torrent of venomous, defamatory, and often violently anti-Semitic messages to Lasdun (who was raised in a secular Anglo-Jewish family, although his father had been baptized as a Christian), to his agent, and to his other professional associates. According to Nasreen, his manifold crimes include sleeping with his students, arranging for her to be raped, and writing fiction defined by racism and misogyny—entirely fantastical allegations that she nevertheless promulgates on Lasdun’s Amazon page, as well as in comments beneath newspaper articles he has written and on the book-review site Goodreads.com. “Boycott this man, for God’s sake,” entreats one typical missive. “He’s the reason behind terrorism.”

Perhaps most bizarrely, Nasreen identifies Lasdun as the linchpin of a vindictive Jewish cabal consisting of his agent—whom she’d met through Lasdun, as a potential client—and a freelance editor who had worked on her novel. They’re stealing her work, she insists, to give to other writers (some of whom are also singled out for direct attack) as part of a Zionist, anti-Muslim conspiracy. Neither a supporter of Israel’s military policy nor a religious Jew, Lasdun sees a strange parallel between his preposterous characterization as a Zionist “racketeer” and the previous experience of his father, a renowned architect whose 1982 design for the rebuilding of the Hurva synagogue in Jerusalem elicited anti-Semitic hate mail. “Overt anti-Semitism is rare today,” muses Lasdun, “and it seemed to me noteworthy that my father and I, neither of us exactly representative Jews, had both been at the receiving end of it.”

The vital difference between his father’s plight and his own, of course, is that large-scale defamation in the Internet age is laughably easy, given the Web’s untrammeled freedoms, its rife opportunities for casual fraud, and what Lasdun calls its “multiplying effect”: “Who else has seen what you have seen? ... Who has copied it, posted it elsewhere, emailed it to a friend? One never knows, but where malice is involved, one quickly succumbs to the worst suspicions.” As he grippingly conveys, the idea of reputation has consequently acquired both a new fragility and a new importance, in an echo of a bygone era. Whereas over the course of the 20th century, civilization evolved away from relying on hearsay to gauge an individual’s trustworthiness, with the emergence of the Internet, “the arbitration of reality began to pass back from the realm of verifiable fact to that of rumor and report.” As for, say, an Elizabethan merchant or a Victorian governess, today a person’s “good name” is susceptible to baseless sullying, and a “stain on your honor” may equal catastrophe.

And so far, the legal system has not caught up with these innovative ways of ruining someone’s life. Early in Nasreen’s campaign, Lasdun tries reporting her to the FBI for hate crimes—a federal offense—but is met with little more than polite indifference, even slight contempt. And though an NYPD detective confirms that Lasdun is the victim of “aggravated harassment,” a misdemeanor, Nasreen has by this time moved back to California from New York, and is not considered a worthy case for extradition. (It’s worth noting that the Justice Department also declined to bring cyberstalking charges against David Patraeus’s mistress Paula Broadwell for her harassing emails to Jill Kelley.) Would the reaction of the authorities be different were the sexes of the parties reversed? It’s hard not to think so. But while Nasreen’s self-styled “verbal terrorism” is not classified as a bona fide threat—as, arguably, it would be if directed at a woman by a man—the psychological torment she inflicts is as debilitating as a bodily injury. The “nature of a smear,” Lasdun points out, “is that it survives formal cleansing, and I felt the foulness it had left behind, like an almost physical residue.”

With no effective legal recourse, Lasdun falls back on literature to endure and process his trauma. A curious feature of his situation is the thematic resonance shared by his fiction and the Nasreen saga: Lasdun’s novels and stories are masterfully replete with Kafkaesque paranoia, delusion, deception, and persecution. Thus, as a person for whom literature and life are so startlingly intertwined, he naturally contextualizes his own true-crime tale within established literary frameworks, drawing persuasive analogies from Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, the writings of D.H. Lawrence, and Patricia Highsmith’s Strangers on a Train.

Still, the one weakness of Lasdun’s account is the extent to which he views Nasreen as a literary figure, and her vitriol as part of some timeless, mythical drama, rather than acknowledging the obvious truth: she is deeply mentally ill. Admitting that his motives are partly literary, that someone with a psychiatric disorder is not a “morally engaging antagonist,” Lasdun is also understandably reluctant to absolve Nasreen of the agency and responsibility that sanity entails, which is perhaps why he shies away from digging into her actual condition. The NYPD detective, on reviewing her rage-filled emails, astutely diagnoses her as “borderline.” Lasdun chooses to interpret the word as a mere metaphor, remembering that Rilke’s Angel from the Duino Elegies, frequently alluded to by Nasreen, is described by Heidegger as a being for whom “borderlines and differences ... hardly exist any longer.” Yet on top of being a brilliant meditation on some of the thorniest issues of contemporary society, Give Me Everything You Have, despite Lasdun’s protestations, is a valuable portrait of borderline personality disorder, of which he unwittingly provides the most concisely accurate definition ever written. To deal with Nasreen, he marvels, is to be “confronted by something unassuageable and beyond all understanding: a malice that has no real cause or motive but simply is.”