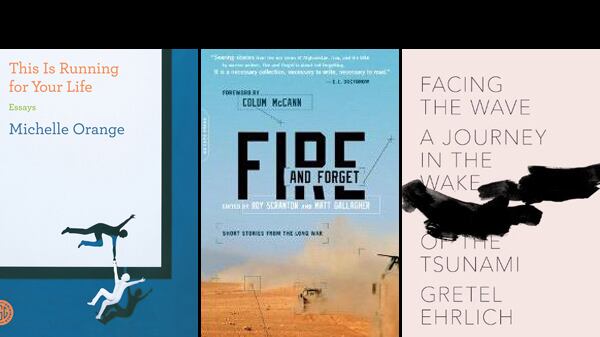

By Michelle Orange

A brilliant collection of essays on modern life, and ways that technology and connectivity are changing how we interact with the world.

The title of a new collection of essays from critic Michelle Orange, This Is Running For Your Life, is so striking in part because it is such an unspoken but recognizable feeling about the way we currently spend our time on earth. As Orange brilliantly breaks down the state of modern life and how it stands in relation to technology and the commoditized image, she tells us much of what we already have intuited, but might have been afraid to admit to ourselves. As she writes about the new method of witnessing public spectacle from behind the lens of a smartphone camera: “If cameras were originally used… to collect the world, the atomic device known as the digital camera has more of a self-reinforcing quality, sucking a fluid moment in at one end and spritzing its owner with eu de permanence out the other.” This book is not only a comprehensive cultural portrait of our relationship with technology but also time itself, in the changing ways that we mediate it and consume it. There is a whiff of that least-lauded strain of Jonathan Franzen, his Luddism, (something which notably didn’t raise nearly so many hackles when it was in the mouth of Norman Mailer before him), but for those of us inclined to agree that we have created a very tricky and very serious new set of problems for ourselves, Orange is a worthy champion.

Edited by Roy Scranton and Matt Gallagher

A visceral, all-too-real collection of short stories by veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The years following WWII saw the publication of many now-canonical books by veterans, such as Mailer’s The Naked And The Dead, Heller’s Catch-22, and Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five. Veterans were largely at the helm of the American literary world, not only by coincidence but indeed because of their treatment of the wartime experience. It is now the twelfth year since the beginning of America’s “War on Terror,” and the dearth of literature by veterans is a national shame; not for the veterans themselves, who surely are as expressive and talented as the veterans of fifty years ago, but for the cultural apparatuses that have decided to ignore their voices. Fire And Forget, a collection of short fiction from fourteen veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, aims to correct that imbalance. This is fiction as good as any you’ll read anywhere: take for example “Big Two-Hearted Hunting Creek” in which a vet with a major burn wound (“faceless” in more ways than one) seeks the same kind of solace that Hemingway’s Nick Adams found in his river, but sees the excursion quickly degenerate into a squadmate’s macabre show of PTSD. Like all of these stories, it works well as a piece of fiction but even better as a piece of reality. These pages contain a record of the cost of our excursions abroad that is as illustrative as any culture can produce.

By Gene Kerrigan

An Irish cop blurs the line between good and bad in this gripping police procedural.

It should come as no surprise that fiction’s most agile fixture, the most able to adapt to real-time changes in the actual world, would be the hard-boiled detective. The recession may have blighted the landscape of Ireland with closed factories and shuttered businesses, but cop Bob Tidey “Is in the law and order business, and whatever else went belly-up there’d always be hard men and chancers and a need for someone to put manners on them.” Bob’s counter-point in The Rage, the third crime novel from Dublin-based Gene Kerrigan, is low-life recidivist Vincent Naylor. Fresh out of jail on an assault charge, Naylor has decided that the next time he goes to jail “it would be for something worthwhile,” such as the heist of an armored car. There are other characters that you might expect to see, like the nun with the powerful secret, but the pleasure in reading Kerrigan is in his unwillingness to let his characters line up along moral dichotomies; the baddies are still plenty bad, but the good guys aren’t always that good.

By Phil Lapsley

The story of the proto-hackers who figured out how to game the phone system and get their kicks on Ma Bell’s dime.

Exploding The Phone opens like a cold war spy caper, with a young, incurably curious Harvard student discovering a cryptic message in the classified section of the student newspaper in 1967. When he responds, all he receives is another riddle, which he’ll have to solve if he wants to earn the trust of the shadowy figure with the odd mailing address. As he digs deeper, he discovers that the secret community he is on the verge of infiltrating isn’t the CIA or the KGB but the fledgling group that would one day call themselves the “Phone Phreaks,” a loose society of people dedicated to investigating and exploiting flaws in the international phone system. The product of years of research by Phil Lapsley, who had to contend with the vestigial reluctance of those involved to even admit their participation, this is the eminently interesting and completely original history of the proto-hackers (counting among their number a couple of youngsters named Steve Wozniack and Steve Jobs) who figured out the tricks that would take advantage of Ma Bell. The most tangible spoils of their mischief was their freedom to make unlimited free long-distance calls, but much like the more good-natured wing of today’s flash-mobbing internet tricksters, it was more about the medium than the message, and the elicit fun of harmlessly breaking the rules.

By Gretel Ehrlich

A haunting elegy and story of renewal in a world torn apart by disaster following the 2011 disasters in Japan.

Things can get a bit dicey when we begin to speak of “national character,” but in Japan’s response to 2011’s triple disaster of earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear meltdown, the world saw a people react to biblical hardship with inspiring decency, dignity, and resolve. There to document the recovery and bear witness to the human suffering was Gretel Erlich, returning to a land she loves in order to pay it tribute by recording one of its darkest and also most triumphant hours. Erhlich writes beautifully, with a poet’s sensitivity towards not only what to write but also what to observe: “Trying to get back to the highway, we drive on a potholed road so narrow, we almost go through the front room of another ravaged house. A Buddhist priest walks knee deep in slush among buildings that have uprooted like trees. He bows toward a submerged shrine.” The power of this book is derived from such contrasts: the worst imaginable physical devastation, which literally remade the landscape, met with unflinching humanity. This haunting song for the dead should not be missed.