On Valentine’s Day, Chicago named a Mexican cartel boss public enemy No. 1, the first person to be so designated since Al Capone.

As announced by the Chicago Crime Commission on the 84th anniversary of the Saint Valentine’s Day massacre—in which Capone’s men gunned down seven rivals—the new public enemy No. 1 is Joaquín Guzmán Loera, head of the Sinaloa drug cartel. His nickname is El Chapo, which is Spanish slang for “shorty.”

The commission noted that Guzman is under federal indictment for running up to 2,000 kilograms of cocaine through Chicago. He is also alleged to send vast amounts of amphetamines and marijuana, distributing it all through “traffic managers” to a host of gangs, so that he is responsible for up to 90 percent of all the drugs on the street, bringing in over $1.8 billion in ill-gotten cash. The commission contends that “El Chapo has easily surpassed the carnage and social destruction that was caused by Capone.”

Capone “was an amateur compared to Guzman,” says Arthur Bilek, executive vice president of the commission, which pioneered the concept of most-wanted criminals when it named Capone public enemy No. 1 in 1930.

But Bilek acknowledges that the Chicago police have not yet directly tied Guzman to any particular killings in that city. Bilek argues that by supplying the gangs with drugs, Guzman is fueling their conflicts.

“Guzman’s fingerprints are on these guns,” Bilek says, though he acknowledges that El Chapo cannot be held responsible for “the bang-bang kind of stuff that goes on the street here,” claiming the life of “the little girl who got shot two weeks ago.”

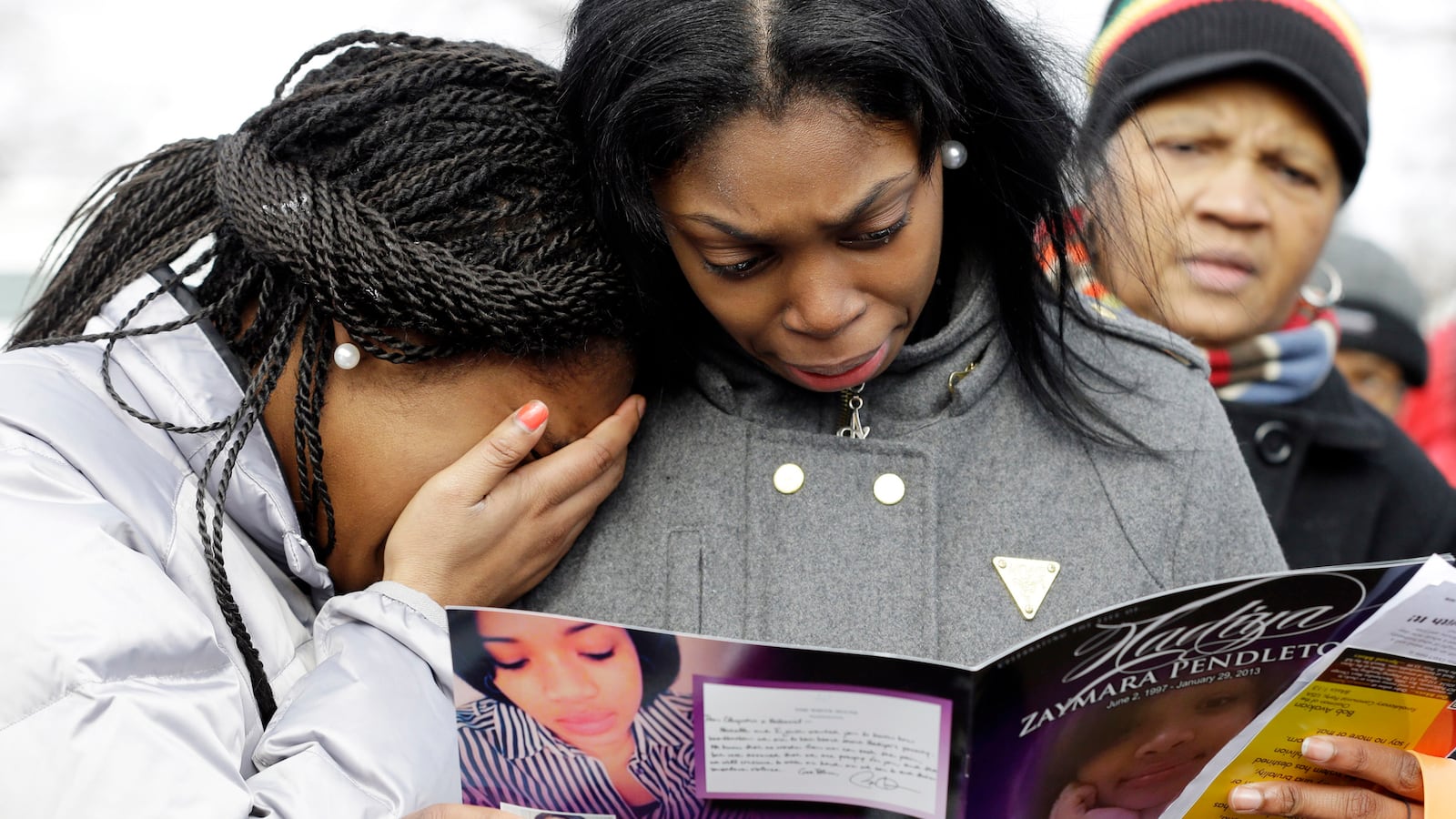

The little girl being Hadiya Pendleton, the 15-year-old innocent who was killed by a stray bullet a week after performing at President Obama’s inauguration. She was killed by another sort of shorty, the street term in Chicago for the 100,000 or so younger members of city’s 300 gang factions.

The real public enemy No. 1 in Chicago has 100,000 young faces. Some cops say they almost wish there were a single Capone-like public enemy around who could be pressured into restraining them.

It is these shorties who are committing most of the mayhem in the city, and more often than not it is unrelated to drugs or to controlling territory. The more common motives are revenge or a personal affront. The perception of even minor disrespect can trigger gunfire.

In the Pendleton case, two young men from the SUWU gang were allegedly seeking retribution for attacks by members of the 46-Terror gang. The two SUWU shorties opened fire on what they mistook for rival shorties in a park, huddled under a canopy during a rainstorm. The targets were in fact a group of eminently blameless teens who had just taken final exams. There was no shelter from the bullets, and Pendleton fell fatally wounded.

Police subsequently arrested 18-year-old Michael “Kellz” Ward and 20-year-old Kenneth Williams. A fellow shorty tweeted his support and actually suggested Pendleton was to blame for hanging out with her equally upstanding friends in a park where the opposing gang, or “opps,” sometimes passed through.

“Free then suwu killas kenny and kellz. Mfkas shouldn't hang where the opps be.”

A subsequent tweet read:

“Catch a body and forget about it i got bad memory.”

And there was:

“Its about time for another opp to die. They be talking like we ain't drillin.”

“Drillin,” meaning in this case to shoot. The term was coined by the Chicago rapper Pac Man, who fell victim to the word’s new meaning in 2010, when he was killed.

The alleged killer in the Pendleton case was Ward. He is also nicknamed Chief Kiael, but nether neither he nor anybody else seems to be the chief of SUWU. They are all chiefs, and none of them are. There is no Capone, no Guzman or any other kind of leader for law enforcement to target.

Chicago Police Superintendant Garry McCarthy declared war on all the members of SUWU, just as he did on the leaderless Maniac Latin Disciples after one of its gunmen shot two little girls in a park last year. McCarthy announced he would again employ the only strategy that holds promise against a gang that has no Capone. “Group accountability,” McCarthy says.

The principle is that when any member of the gang commits a violent act, the entire group is made to suffer consequences. The hope is that members end up restraining each other rather than incur the wrath of the police.

Of course, the accountability ultimately extends beyond the immediate group to all of us who do too little to address a perpetual crisis that has some calling Chicago the Wild, Wild Midwest, or Chiraq and leaves so many young people valuing life so little that they seek a sense of worth in the power of death. Theirs and therefore ours is a world where other youngsters have nicknames such as Drill Clinton of Drillery Clinton or simply Murder.

The very fact that a city can have 100,000 young public enemies raises the question why there are so many.

Hadiya Pendleton’s godfather, Damian Stewart, became a Chicago police officer after his 12-year-old brother became an innocent victim of gun violence. He despairs of ever being able to get guns off the street. He can think of only one way to keep the shorties from wanting to pick up a gun. In this regard, Stewart is in agreement with a former leader of the Black Disciples gang. They both distill it to one seemingly improbable word that happens also to be the byword of Valentine’s Day.

“Love.”

Stewart summarizes what he believes to be at the core of the shorty with a gun: “I don’t get no love, I got no love.”

He says that if the shorties did get love, they just might have love. He says that if the fathers do not provide this love, then others have to step up and try. The result just might be a kid who values himself and even life itself enough not to take it.

“You can’t take the guns, but you can give them love,” Stewart says.

Stewart is not the only cop who reaches out to what is best in kids while trying to protect the city from what is worst in them. The ex–Black Disciple is not the only former gangbanger trying to do the same. Many schoolteachers struggle mightily every day, as do some of the better clergy.

The clergy include Rev. Corey Brooks, who was concluding the funeral for a young gunshot victim last November when one of the mourners was shot to death directly in front of the church in a not-uncommon eruption of violence involving members of the same gang.

“It was out of control,” says Brooks. “Nothing like that should happen in front of a church. It shouldn’t happen anywhere.”

By chance, the church was Saint Columbanus, which Capone’s wife and mother attended, the mother a daily communicant. Capone is said to have contributed toward the stained glass. The monsignor there agreed to offer a blessing when Capone was buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery.

That Catholic burial ground is adjacent to Mount Hope Cemetery, which has become the burial ground of choice for rappers such as Pac Man and alleged gang members such as the young man shot down while leaving a funeral for another gun casualty.

None of them seem to have been even indirectly a victim of the city’s new official public enemy No. 1. That is not to deny that Guzman has perpetrated murder and torture in Mexico on a scale that truly does dwarf whatever Capone did in Chicago.

Guzman may actually be, as Bilek of the crime commission says, “the deadliest, most powerful, and ruthless criminal in history.” We should join Bilek in hoping that the cartel kingpin he terms “a phantom” who is “almost invisible” will be brought down soon after being named public enemy No. 1, as happened with Capone. And it is well worth remembering that if you take drugs north of the border, you may well be helping to perpetuate the carnage south of it.

But in Chicago, it is hard to think of Guzman as public enemy No. 1, knowing that Brooks has gone on to preside over the funerals of not just the mourner shot in front of the church but also of three more young victims of gun violence in January and another this month.

“So far,” Brooks says.