If the International Olympic Committee reverses its decision and keeps wrestling as part of the Games, the ancient Greeks will be partly the reason. A sport with such long pedigree, critics have argued, must remain central in an athletic festival founded on classical models. Yet from the perspective of a classicist like myself, the IOC’s decision makes a certain sense. The modern Games—or at least, the carefully packaged version televised to American viewers—have evolved in a way that defines our distance from Greek antiquity more than our connections to it.

Ancient Greece loved wrestling. Its language and literature is replete with metaphors drawn from the sport; a word that first meant “to trip up one’s wrestling opponent” was the standard way to describe any type of overthrow or trick. Mythic heroes, especially Heracles, wrestled monsters and wild beasts at the beginning of time. The Greeks introduced wrestling and boxing in their first expansion of the Olympic games, which initially consisting only of footraces, along with an event called pankration, a vicious style of fighting that combined the holds and grapples of wrestling with the punches of boxing and added kicking, choking, and head-butting.

Pankration never found its way into the modern Games. It was the only sport banned by Pierre de Coubertin, leader of the late-19th-century movement that revived the Olympics, though he was in other ways a devotee of the classical model of competition. The modern Games thus parted ways with their ancient counterparts at their very inception. The sport that exemplified the spirit of the agon—the one-on-one, hand-to-hand test of strength that thrilled the ancient Greeks, whether they found it in sports, literature, or combat—was banned.

The Greek word agon is the root of our words “antagonist” and “agony.” The classical world revered sporting events, like pankration and wrestling, in which two contestants engaged one another in such a way as to inflict pain. If wrestling now follows pankration into Olympic exile, then an interesting first-in-first-out reversal would be taking shape. Two of the three events first added to the ancient games would be the first to depart from the modern ones. And the third, boxing, has also sometimes come into question, including in 1912 when host nation Sweden refused to permit it.

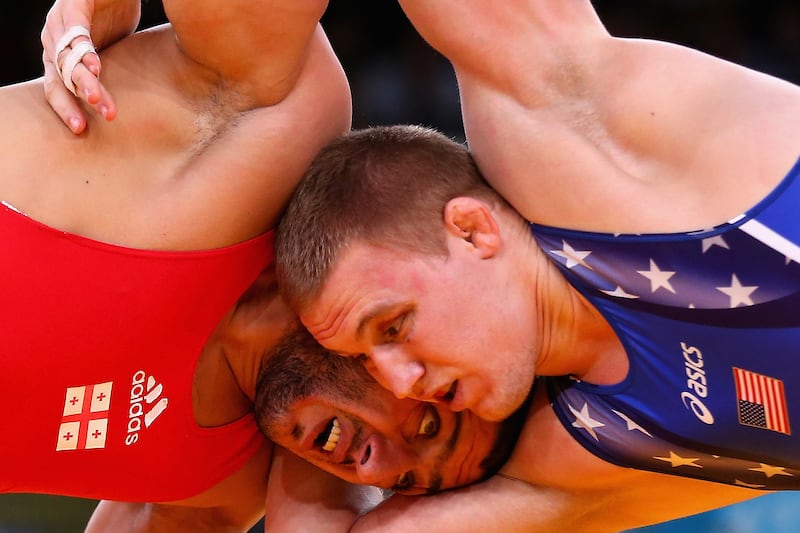

For the Greeks the agon was where human nature was tested to its limits. A one-on-one, no-holds-barred contest required not only strength and skill but a quality we moderns embrace far less easily than our ancient counterparts: aggression. Ancient athletics often resembled warfare, by design; the city-states that sponsored sports festivals needed citizens who could kill their foes at close range. It is no accident that the last event added to the ancient Olympics, a footrace by runners wearing infantry armor, was virtually a basic-training drill for young soldiers, nor that a track-and-field event that survives today from antiquity features the hurling of a javelin spear.

The modern Games have de-emphasized this martial model of athletics and instead gravitated toward two kinds of spectacle that, to the Greeks, would not have seemed to be contests at all. Team sports, a phenomenon utterly unknown to the ancient world, have claimed an increasing share of the Games themselves and an ever-greater percentage of their televised avatar. The same is true of competitions like diving, figure-skating, and gymnastics, in which athletes perform solo, in serial displays, before a panel of judges. The two-man confrontation that typified the agon, in other words, has given way to spectacles that fill the screen with crowds of athletes or focus our gaze on individuals seen in isolation.

The pleasures afforded by such spectacles are well suited to the values of modern Western society. The smooth collaboration of, say, a basketball squad mounting a full-court press highlights social virtues that define the age of corporate capitalism and globalized democracy. At the same time, an individual’s quest for ideal grace of movement, seen in the gymnast’s floor routine or the platform diver’s aerobatics, respond to our collective need for self-expression and self-actualization.

These solo performers test themselves not just against an opponent but against the ideal of the perfect score, much like artists striving for ideals of beauty and harmony. Since they perform in sequence, they never engage their opponent and, except for a brief handshake or hug at the event’s end, the two never even come face to face. The sense of an agon, a duel, is diminished, in favor of an individual’s pursuit of a “personal best.”

Something essential has been lost as these solo performances have gradually pushed agonistic events out of the Olympic spotlight. Few would wish for the return of the pankration to the Olympics, an event that often brought death to the loser (or even, in one notable case, to the victor). But wrestling, a more structured and rule-bound event, is a different story. It stands as a reminder of where the Olympics came from: the classical Greek fascination with one-on-one tests of prowess and aggression—a last vestige of the ancient agon still surviving in the modern Games.