Sons following their fathers—that’s the Chicago way.”

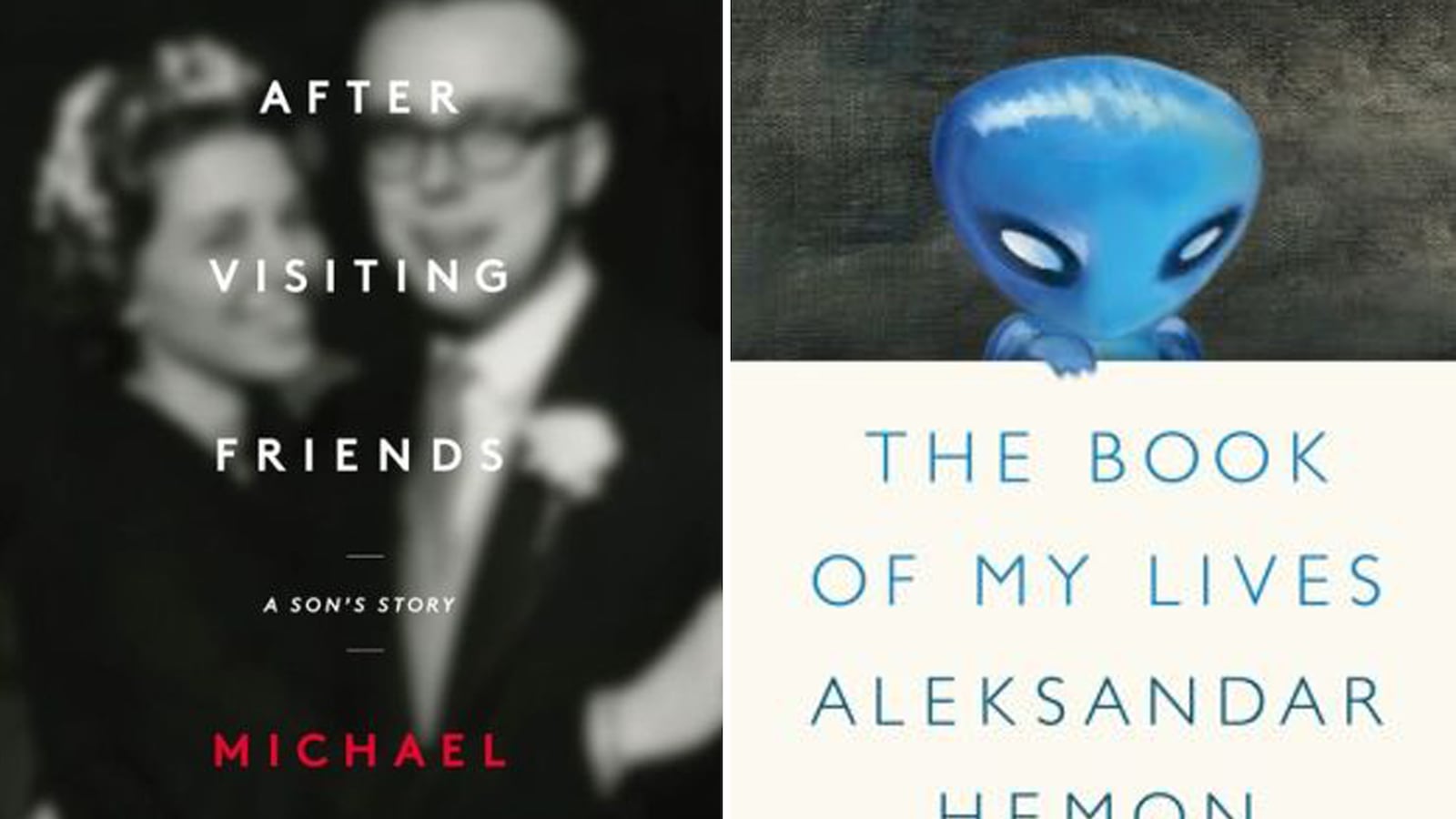

Such is the gauntlet taken up by Chi-town native Michael Hainey in his memoir After Visiting Friends, where that line is to be found. It is written, as is much of the book, as incantation, a rhythmic thumbing over rosary beads back into time, back up the genetic chain in pursuit of the great mysteries. It is written in direct reference to Chicago’s Mayor Daley, son of the former Mayor Daley. But we are considering also Hainey, son of a newspaper man, and now the Deputy Editor of GQ, who has returned home to investigate the mysterious circumstances surrounding his father’s death when Michael was just 6. This son has begun thrumming the strings of hereditary determinism, and is finding them holding taut.

If there is a gloom in that sentiment, there is also a comfort, a security in its bonds. This is the framework in which we feel placed, a feeling for which Aleksandar Hemon is desperate when he arrives in Chicago after expatriating from Bosnia in 1992. “If my mind and my city were the same thing then I was losing my mind,” he writes of that time in The Book of My Lives. “Converting Chicago into my personal space became not metaphysically essential but psychologically urgent as well.”

“Chicago,” Hainey writes. “I am of that place.” And for him, the land, even that which is constructed by man, is resonant. “From my grandmother’s attic,” he writes, “I could see the garbage dumps beyond the railroad tracks. They had been filled years before I was born. Covered with new soil. Sodded with fresh grass. New land.” This new land is built atop the former stock yards, a slaughterhouse converting animals into base, consumable goods, “churning all of it into the bounty of America. This was the land of Swift, the kingdom of Armour. Chicago as the disassembly line. Chicago—how fast and how efficiently a creature could be reduced. Rendered. Broken down.”

Chicago is the space where these two books meet. It is, for these two sons, both born in 1964, the fulcrum for their great labors. This frigid city, itself a symbol of memory, of erasure, and of survival—the “Second City,” built atop the ashes of its former self—is where these writers hope to find the material with which to rebuild themselves. In Hainey’s Chicago, the very air is menacing (cold breaths feeling like “inhaling shards of glass”), but there is strong nostalgia in its powerful currents. In his father’s day, there were still men who remembered what it was like when Capone ran things. The police and the papers worked together, oftentimes in covering things up. Bars were full of men in shirtsleeves drinking Old Styles and boilermakers, men with secrets, who abided by “the newspaperman’s code”: silence. Hainey’s is “a Chicago story,” like the muckraking tales of that era, “A story about deceit. About men putting in The Fix.”

For Hemon, this metaphysical city comes to mean everything for his newfound reality. “I wanted from Chicago what I’d got from Sarajevo,” he writes, “a geography of the soul.” But contra to Freud’s famous metaphor of an archaeologically profound city of Rome as an individual’s psyche, Hemon is stripped bare by war, cut off from the Sarajevo of his memories. At about the same time Susan Sontag (proud University of Chicago Phoenix) is in Sarajevo, directing Waiting for Godot, Hemon is cut off from his own adolescence and from his family. And, once removed, he becomes fixated on the divide between his interior and external worlds.

Reminiscing on life in his hometown, Hemon writes, “physically and metaphysically, I was placed.” Wrapped in the synaptic webbing of family, his neighborhood gang, and the smoke and gossip wafting from his local kafana or café, his identity is given external definition. “Back then the city—a beautiful, immortal thing, an indestructible republic of urban spirit—was fully alive both inside and outside me.” In America he struggles to define himself, but finds little in Chicago to place him. “A few years later,” he writes, “I would find a Bellow quote that perfectly encapsulated my feeling of the city at the time: ‘Chicago was nowhere. It had no setting. It was something released into American space.’”

Once opened, this fissure between internal and external splits Hemon apart, giving him, effectively, double lives. There is the public life where he tries to master English and gain purchase on the slippery slope of solvency through a series of menial jobs (including canvassing door-to-door for Greenpeace). And there is the private life, in which he is working to become a writer. In this endeavor he is fantastically successful—a MacArthur “genius” grant, a Guggenheim fellowship, and nominations for several national book awards. But even that hard-won critical and commercial embrace can provide him no comfort when his infant daughter Isabel is struck with a rare brain tumor. The experience of this unimaginable horror (“Even if you could imagine your child’s grave illness, why would you?”), of living behind the glass of catastrophe, cordoned off from the rest of life, is the subject of his blistering, National Magazine Award-winning essay of last year, “The Aquarium,” collected here as the book’s final work. We are in Didion country here, hearing echoes of her famous line (“When we talk about mortality we are talking about our children.”), and Hemon bottles his own white-hot grief in similarly elegant sangfroid.

When, during Isabel’s treatment, her sister Ella develops an imaginary friend—a brother, actually—and imagines for him a reality that rights the cosmic wrongs done to Isabel, Hemon recognizes, he says.

In a humbling flash that she was doing exactly what I’d been doing as a writer all these years: in my books, fictional characters allowed me to understand what was hard for me to understand (which, so far, has been nearly everything). Much like Ella, I’d found myself with an excess of words, the wealth of which far exceeded the pathetic limits of my biography. I’d needed narrative space to extend myself into; I’d needed more lives… Narrative imagination—and therefore fiction—is a basic evolutional tool of survival. We process the world by telling stories and produce human knowledge through our engagement with imagined selves.

Those familiar with Hemon’s imagined selves will likely (correctly) have inferred that he, like Brik in The Lazarus Project and Jozef in Nowhere Man, narrowly missed the siege on his native Sarajevo while visiting Chicago as part of a cultural exchange mission. For those readers this collection of overlapping essays of Hemon’s cinematic childhood in Bosnia and subsequent struggles as a refugee, will have about it the quality of déjà vu, of a dream slowly remembered upon waking. Indeed, any one with a New Yorker subscription will recognize great swaths of book where it has been excerpted there, will recognize the tale of his family’s heirloom borscht recipe, of the “good sniper” firing above the heads of his grandparents, stranded back in his hometown during the war, to “warm them that he was watching and that they shouldn’t move so carelessly in their own apartment.” For those readers this book will read like a familiar ghost story; a distant chill of recognition wrapped in the dread of knowing what comes next.

We can be forgiven, perhaps, for thinking of Rebecca West, who, in Black Lamb and Grey Falcon reverses Hemon’s trip, heading into the Balkans, but writes, as eagerly, to understand herself through the world in which she finds herself. And, just as she did, Hemon has a dazzling gift for observation, for flipping an ordinary detail into something greater, revelatory—a quality famously achieved by another non-native master of English prose, Nabokov.

James Wood, writing in The New Yorker, compared Hemon’s prose favorably with the Russian’s. “Sometimes,” he wrote, “[Hemon’s] English has the regenerative eccentricity of the immigrant’s, restoring buried meanings to words like ‘vacuous’ and ‘petrified.’” Hemon’s sentences often curl taut before snapping into a sudden, explosive phrase or image. Like the mortar shell craters he finds painted red and “now, incredibly, called ‘roses’” by survivors of the siege, Hemon’s wounds are frequently converted into poetic blooms. Describing one of his old haunts, a parade ground for his apprentice flâneurship, he writes, “I referred to it as the city artery, because many Sarajevans promenaded along it at least twice a day, keeping the urban circulation going.” Ten pages, five years and a war later, he returns to this stretch and finds, “The street I’d thought I’d owned, and had frivolously dubbed the city artery, was now awash in the actual arterial blood of those I’d left behind.”

Assembled in a kind of discursive cubism the tiles of Hemon’s essays make for a rather exquisite mosaic, but Hainey’s project is far more directional, contiguous—the laying of a cross-continental railway—and his accomplishment significant. When, in high school, Hainey discovers a set of incongruous and even contradictory facts (including the vague line that serves as the title of the book) in his father’s obituaries, his childhood suspicion, his lingering doubt about the veracity of events as they’ve been told to him develops first into purpose and then into obsession. Hainey returns to Chicago, again and again, and to the exact scene of his father’s mysterious death, before traveling to Nebraska, Ohio, and ultimately San Francisco, half hoping he will stumble upon a ghost (or even his real father incarnate), in search of truth.

My father,” he writes, “from the day he died, I wanted to grow up and be just like him. To follow in his footsteps.” He wants to learn the secret handshake, to gain entry into his father’s exclusive club, the world of newspapers. “A world of men, of stories, of knowledge.” After college, he enters this world as a “stringer,” as a reporter is often called. “I wanted so much to belong,” he says. “In my head I saw myself continuing my father’s work. Learning the trade so I could finish what he began. A newsman in the city. In a line with him… Keeping the line going. Strung together.”

He grows up. He makes good, with a prestigious position at a respected publication, walking, and talking just like the man he so closely resembles. But soon after he outlives his father (who died at 35), Hainey turns about face. The quest to become himself displaces his goal of becoming his father and so he returns home in pursuit of his ghosts. He reports the story. He reconstructs his father from a scrap book. “It was left to me to reassemble him,” he writes. “I learned to make sense of the remnants, to find meaning in the missing pieces. A man of paper. The more I touch it, the more it crumbles.”

At first shunting along, collecting images and memories freighted with emotion, gathering mass and force, the book eventually develops the rapid momentum of a noir thriller. Hainey chases down weak leads in a cold case. He tears apart the fictions and fantasies he’s lived by for five years, ten years, twenty. “To me,” he writes, “perseverance is the great trait.” And he perseveres for more than a decade, piling up the facts he finds into plot, pulping them into hard, declarative sentences, hard-boiled to their bones.

He writes as if he is just learning again to trust words, words that can hide or bend truth and meaning. He issues them carefully, a broken-hearted man, proceeding with great caution, lest he be broken again, in a kind of hard-hewn poetry. “This was in March,” he says of an early trip home. “Thick of Lent.” It is a lovely line, pairing a homonym for fleshiness with the abstemious holiday of giving up stuff, and exemplary of Hainey’s deft parsing of the facts, but not just the facts.

“Everybody needs his memories,” Bellow wrote, in Mr. Sammler’s Planet. “They keep the wolf of insignificance from the door.” But, for the men Hainey comes across in his search for truth, the memories are the wolves, hounding them across the prairie of their lives. These men drink, dissemble, and hold their tongues, and block Hainey’s passage toward the truth at every pass. But early in his life, Hainey is given explicit instruction in this code of silence, the code of men—instruction given, ironically, by his mother, who teaches with the gospel of The Godfather (“Don’t ask me about my business, Kay”).

“Omertà,” concedes the not-firstborn son Michael writing the book. In the silence it is the things in life that become pregnant with meaning and everywhere you look in Hainey’s Chicago the physical world is screaming with import. There is the game of ghosts he played when just a boy: “Victory depends on defying the ghosts. Evasion. Elusion. Finding home.” His grandmother, who is a great through line in his process for unearthing his father, is checked into Resurrection hospital. His widowed mother plays solitaire. Watergate becomes a story about “Men, searching for answers to what men knew and when they knew it.” His ghostly father was nicknamed “Bones.” And then the city of Chicago, whose motto is “I will,” becomes a part of Hainey’s determined quest.

Hacking through the tangles of conspiracy and silence, Hainey is as dogged as Marlowe or Spade, but his path is illuminated by a warmth of spirit those sleuths lacked. Of his grandfather he writes, “I want from him what I want from any man in my life. A voice. Someone to talk to. Someone who will tell me the knowledge I should know, tell me the ways of the world, guide me. An arm around my shoulder.” It is a cold country, manhood, and we are isolated from our fellow citizens by mum masculinity. Without those arms around our shoulders guiding us, helping us to navigate that terrain, it is easy for us to get lost, to assume others are in possession of the Atlas of our sex we lack. “To this day, still,” Hainey writes, “I scavenge for scraps in the hearts and minds of men I meet. Forever searching, believing the answers are out there. Somewhere.”

Hainey is successful in finding a great many answers. “In the end,” he writes, “my father’s mystery is undone by what he loved most and what he lived for: good reporting.” And in reporting the mystery, he not only unravels his father’s story but writes his own. “Because we without fathers must out of necessity create ourselves.”

Another such fatherless boy who created himself thusly, and is listed among Hainey’s acknowledgements, is Albert Camus. The first in his family to learn to read, Camus completed perhaps the greatest word-based self-creation possible, winning the Nobel Prize. Which makes it strange that Hainey, as Hemon does in his book, seems to discount the higher value of turning his story into literature. In Hainey’s case, he very nearly aborts the project after making his greatest breakthrough for fearing of hurting others with the truth.

When Hemon discovers that his former mentor, a literature professor whom he admired, has become an excited advocate of the Serbian siege on his city, a defender of the camps and a denier of the atrocities around him, Hemon says, he “excised and exterminated that precious and youthful part of me that had believed you could retreat from history and hide from evil in the comforts of art.” Later, when his daughter is dying, friends and family repeatedly proclaim there are “no words,” that can appropriately describe or comfort them from the horror. “Whatever knowledge I’d acquired in my middling fiction-writing career was of no value,” he says. “I could not write a story that would help me comprehend what was happening.”

He has reached that point beyond which we no longer feel the succor of literature or religion, a realm for which we are forever underprepared. Entering this place we are let down by our teachers, by our heroes and our prophets. And, indeed, our suffering in itself is not ennobling, is not, as Hemon scoffs, “a step on the path of some kind of enlightenment or salvation.” It is suffering and suffering alone.

But still we chip away, mapping that dark country, describing it, transcribing it in black and white. And, as that great son of Chicago Bellow said in his Nobel acceptance speech, paraphrasing Lawrence, “There is an immense, painful longing for a broader, more flexible, fuller, more coherent, more comprehensive account of what we human beings are, who we are and what this life is for.”

This is what Hemon and Hainey are after, and, though they may deny it, also what they are fulfilling. Their suffering may not have been ennobling, but their journeys have been nothing less than heroic.

If, to return to West, “during the next million generations there is but one human being born in every generation who will not cease to inquire into the nature of his fate, even while it strips him and bludgeons him, some day we shall read the riddle of our universe.”

Here I think we’ve found two.